The PMLN government has decided to apply Article 245 of the constitution and deploy the army to manage law and order and enhance the security of “sensitive installations” in the capital territory of Islamabad for three months starting August. The decision was probably taken after detailed consultations with the military leadership over its modus operandi and politico-legal objectives and consequences.

Article 245 says that that thee armed forces shall act under the directions of the federal government to defend Pakistan against external aggression or threat of war, and subject to law, also act in aid of civil power when called upon to do so. The government’s orders cannot be called into question in any court.

Clearly, since external aggression and threat of war are not an issue currently, the government expects to use the army to control any law and order situation arising out of the “long march” of Imran Khan and Dr Tahir ul Qadri on August 14th. Both are talking of a “revolution” not just to overthrow the government but also to radically change the political system of electoral democracy as we know it. Therefore, it may also consider applying Article 245 to Lahore and Rawalpindi if the situation so requires.

The political situation today is a throwback to 1977 when the PPP government of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was faced with a popular Pakistan National Alliance movement across the country demanding fresh elections and responded by clutching at Article 245 to control the angry and motivated crowds in Karachi, Hyderabad and Lahore. When the government’s order was challenged in the Lahore High Court, the then Attorney-General Yahya Bakhtiar told the court it had no jurisdiction in the matter because Article 245 amounted to the imposition of a “mini-martial law” in the affected areas. But the Lahore High Court (LHC) struck this formulation down.

This lesson should not be lost to the PMLN government today, not least since the courts are overly aggressive in defending their newly won extended writ jurisdictions. Indeed, it is more than likely that petitions will be filed directly to the Supreme Court under Article 184(3) that protects the “public interest” (which is exactly what Imran Khan et al are talking about).

A second lesson should also not be ignored. After the “mini-martial” law was struck down by the LHC in 1977, the crowds got such a political fillip that the army under General Zia ul Haq was emboldened to intervene on its own account and overthrow the Bhutto regime by a coup d’etat.

The situation is perilous. Imran Khan is not talking of a soft gathering in Islamabad that will peacefully disperse after a few speeches. He is threatening a storm akin to the one that overthrew the regime and political system in Egypt three years ago. But the experience of Egypt is instructive. The army was called out in aid of civil power to protect the Hosni Mubarak regime from popular discontent on the streets but soon thereafter ousted the regime on the pretext of holding new elections and subsequently seized power on its own account. Much the same thing happened in Pakistan in 1977.

But if the lessons for PMLN are clear enough, these should also not be ignored by Imran Khan and Dr Qadri. The long-term beneficiaries of the army’s intervention in Pakistan 1977 and Egypt 2011 were not the political leaders of the popular revolt but the clique of army generals who carried out the interventions.

There is another factor to consider. In 1977, a coup was made after Mr Bhutto refused to budge. But in Pakistan 1993 and Egypt 2011, regime change followed by elections became possible after Nawaz Sharif and Hosni Mubarak respectively agreed to step down under military pressure. But the Nawaz Sharif of 2014 is not the Nawaz Sharif of 1993 or the Asif Zardari of 2008 (when General Ashfaque Kayani was able to play a role in stopping Nawaz Sharif’s long march and leaning on the government to restore the judges). Should push come to shove as a consequence of Imran Khan’s long march, Mr Sharif will not budge even if leads to another martial law. And martial law will not pave the way either for fresh free and fair elections, nor the installation of Imran Khan and/or Dr Tahir ul Qadri at the head of the new regime.

All sides should reconsider their positions in the national interest. Pakistan is not Egypt. Uneven political and regional developments have created a multiplicity of parties and interests. The army and paramilitary forces are already extended in FATA and Balochistan. Relations with neighbours India and Afghanistan are prickly and precipitous. The economy is struggling to get back on the rails. US interest in propping up the army and economy is on the wane, unlike in the past when martial laws were imposed. Political negotiations rather than tsunamis and military aids to civil power are urgently needed.

Article 245 says that that thee armed forces shall act under the directions of the federal government to defend Pakistan against external aggression or threat of war, and subject to law, also act in aid of civil power when called upon to do so. The government’s orders cannot be called into question in any court.

Clearly, since external aggression and threat of war are not an issue currently, the government expects to use the army to control any law and order situation arising out of the “long march” of Imran Khan and Dr Tahir ul Qadri on August 14th. Both are talking of a “revolution” not just to overthrow the government but also to radically change the political system of electoral democracy as we know it. Therefore, it may also consider applying Article 245 to Lahore and Rawalpindi if the situation so requires.

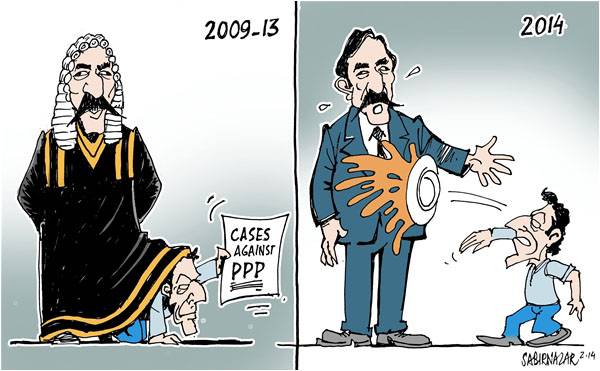

The political situation today is a throwback to 1977 when the PPP government of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was faced with a popular Pakistan National Alliance movement across the country demanding fresh elections and responded by clutching at Article 245 to control the angry and motivated crowds in Karachi, Hyderabad and Lahore. When the government’s order was challenged in the Lahore High Court, the then Attorney-General Yahya Bakhtiar told the court it had no jurisdiction in the matter because Article 245 amounted to the imposition of a “mini-martial law” in the affected areas. But the Lahore High Court (LHC) struck this formulation down.

This lesson should not be lost to the PMLN government today, not least since the courts are overly aggressive in defending their newly won extended writ jurisdictions. Indeed, it is more than likely that petitions will be filed directly to the Supreme Court under Article 184(3) that protects the “public interest” (which is exactly what Imran Khan et al are talking about).

A second lesson should also not be ignored. After the “mini-martial” law was struck down by the LHC in 1977, the crowds got such a political fillip that the army under General Zia ul Haq was emboldened to intervene on its own account and overthrow the Bhutto regime by a coup d’etat.

The situation is perilous. Imran Khan is not talking of a soft gathering in Islamabad that will peacefully disperse after a few speeches. He is threatening a storm akin to the one that overthrew the regime and political system in Egypt three years ago. But the experience of Egypt is instructive. The army was called out in aid of civil power to protect the Hosni Mubarak regime from popular discontent on the streets but soon thereafter ousted the regime on the pretext of holding new elections and subsequently seized power on its own account. Much the same thing happened in Pakistan in 1977.

But if the lessons for PMLN are clear enough, these should also not be ignored by Imran Khan and Dr Qadri. The long-term beneficiaries of the army’s intervention in Pakistan 1977 and Egypt 2011 were not the political leaders of the popular revolt but the clique of army generals who carried out the interventions.

There is another factor to consider. In 1977, a coup was made after Mr Bhutto refused to budge. But in Pakistan 1993 and Egypt 2011, regime change followed by elections became possible after Nawaz Sharif and Hosni Mubarak respectively agreed to step down under military pressure. But the Nawaz Sharif of 2014 is not the Nawaz Sharif of 1993 or the Asif Zardari of 2008 (when General Ashfaque Kayani was able to play a role in stopping Nawaz Sharif’s long march and leaning on the government to restore the judges). Should push come to shove as a consequence of Imran Khan’s long march, Mr Sharif will not budge even if leads to another martial law. And martial law will not pave the way either for fresh free and fair elections, nor the installation of Imran Khan and/or Dr Tahir ul Qadri at the head of the new regime.

All sides should reconsider their positions in the national interest. Pakistan is not Egypt. Uneven political and regional developments have created a multiplicity of parties and interests. The army and paramilitary forces are already extended in FATA and Balochistan. Relations with neighbours India and Afghanistan are prickly and precipitous. The economy is struggling to get back on the rails. US interest in propping up the army and economy is on the wane, unlike in the past when martial laws were imposed. Political negotiations rather than tsunamis and military aids to civil power are urgently needed.