Karachi is the fifth least liveable city in the world, and a place where citizens lack the basic elements of life – safety, clean air, sanitary conditions, drinkable water, uninterrupted electricity and adequate infrastructure. Karachi has few public spaces, public events, or public forums for residents to express diverse feelings of joy, frustration, and identity. Events like the Karachi Eat Festival, cricket (more recently), and the Karachi Biennale aim to bring people together in an inclusive manner.

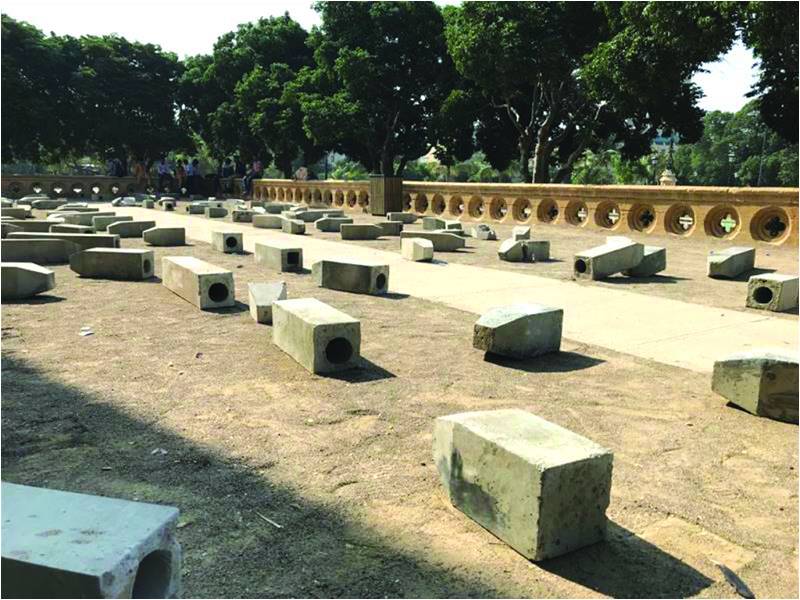

The Karachi Biennale’s first event took place in 2017 focussing on the theme of “Witness.” The current Biennale (which opened on October 27) is curated around ecology. As per its motto, “art, the city and its people will always be at the core of our initiatives.” However, 24 hours after its public opening, the Biennale has betrayed its espoused ethos. Adeela Suleiman’s installation at Frere Hall titled Killing Fields of Karachi, which included a video that showed the killing of Naqeebullah Mehsud, and sculptures symbolising the graves of 444 people murdered extra judicially by police officer Rao Anwar in Karachi.

Naqeebullah Mehsud was an aspiring model, targeted by the police for being a Taliban member (apparently, the Taliban accepts models within their ranks?) who has since been posthumously declared innocent by an anti-terrorism court in Karachi. Rao Anwar is known as an “encounter specialist” - encounter being a euphemism for extrajudicial killings by law enforcement agencies - and has been involved in 444 such incidents (as per the police’s own records) during his time (2014-2018) as Superintendent Police Malir. He retired on January 1, 2019. He has been praised by the ISI for his “exceedingly good performance” and “call beyond duty.” It is no secret who he works with and is patronised by the military establishment, parts of the Pakistan Peoples Party, and land-grabbing developers. He has been indicted in the Naqeebullah Mehsud case, placed on the ECL, and is currently on bail. As the trial continues, his victims deserve to be honoured. Adeela Suleiman’s art aimed to do this.

Adeela Suleiman is an influential contemporary Pakistani artist, head of the Fine Art Department at the prestigious Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture. However, her installation was shut down by unknown plain-clothes men within two hours of opening to the public at Frere Hall on October 27.

The Karachi Biennale Team issued a statement on October 28, saying they were “against censorship of art” and “feel that politicising the platform will go against their efforts.” They allied with the City Government who facilitates their use of public space and felt that the theme this year “did not warrant political statement on an unrelated issue.” Each displayed piece of work undergoes thorough examination before being accepted by the curatorial committee. Despite this procedure, the Karachi Biennale Team has distanced themselves from the artist. Karachi Biennale’s Team’s position values the so-called apolitical and finds it acceptable to silence the stories of 444 residents of Karachi who have died at the hands of the city’s establishment. Art is inherently political, as is the use of public space, and cultural discourse. The Biennale Team has lost a golden opportunity to stand up against those that suppress democracy and freedom of speech. Karachi is poorer for this.

A press conference was organised on October 27 by Jibran Nasir. It was interrupted by Director General Karachi Municipal Corporation Park’s Division Afaq Mirza who felt that Adeela Suleman’s art is vandalism (it appears he is the arbiter on what constitutes art) and instead art must be used to promote a positive image of Pakistan. This toxic thinking tells us to focus on Kashmir, focus on external enemies, on everything but the rot that is in our society. “I’m not saying Rao Anwar is a good man, he’s a number one murderer,” DG Parks said, “but on Kashmir Day, permission was given to depict artwork and culture. Instead, they took it as an opportunity to educate people about Rao Anwar and Naqeebullah and said so many people have been killed by him [Anwar].” The citizens of Karachi have been told: this is not the time to educate people about the injustice in our society. This incident demonstrates that art is only acceptable if it is uncontroversial, pro-establishment, and protective of oppressors. It is not a part of art or our culture to subvert the status quo. If we live in a time of uncritical expression, a petulant establishment, and a subservient intelligentsia, there is little hope for Pakistan.

The Biennale’s overall contribution to Karachi should be recognised. It is difficult to achieve a wide level of engagement without the Government’s acceptance, and security considerations are a reality. However, if the mission was to work towards the public interest, the public interest is not advanced by hiding behind curatorial selection and thematic preferences. It is time for those associated with the Karachi Biennale to investigate the matter, engage in damage control, and begin a discourse based on the truth. For now, the conversations that matter have once again been pushed from the public space into the private sphere. An opportune moment to do things differently, in the open, has tragically been lost and Karachi is a darker place because of it.

The writer is a barrister, PhD candidate in criminology at the University of Cambridge, and consultant for UN agencies in Vienna and Beirut

The Karachi Biennale’s first event took place in 2017 focussing on the theme of “Witness.” The current Biennale (which opened on October 27) is curated around ecology. As per its motto, “art, the city and its people will always be at the core of our initiatives.” However, 24 hours after its public opening, the Biennale has betrayed its espoused ethos. Adeela Suleiman’s installation at Frere Hall titled Killing Fields of Karachi, which included a video that showed the killing of Naqeebullah Mehsud, and sculptures symbolising the graves of 444 people murdered extra judicially by police officer Rao Anwar in Karachi.

Naqeebullah Mehsud was an aspiring model, targeted by the police for being a Taliban member (apparently, the Taliban accepts models within their ranks?) who has since been posthumously declared innocent by an anti-terrorism court in Karachi. Rao Anwar is known as an “encounter specialist” - encounter being a euphemism for extrajudicial killings by law enforcement agencies - and has been involved in 444 such incidents (as per the police’s own records) during his time (2014-2018) as Superintendent Police Malir. He retired on January 1, 2019. He has been praised by the ISI for his “exceedingly good performance” and “call beyond duty.” It is no secret who he works with and is patronised by the military establishment, parts of the Pakistan Peoples Party, and land-grabbing developers. He has been indicted in the Naqeebullah Mehsud case, placed on the ECL, and is currently on bail. As the trial continues, his victims deserve to be honoured. Adeela Suleiman’s art aimed to do this.

Adeela Suleiman is an influential contemporary Pakistani artist, head of the Fine Art Department at the prestigious Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture. However, her installation was shut down by unknown plain-clothes men within two hours of opening to the public at Frere Hall on October 27.

The Karachi Biennale Team issued a statement on October 28, saying they were “against censorship of art” and “feel that politicising the platform will go against their efforts.” They allied with the City Government who facilitates their use of public space and felt that the theme this year “did not warrant political statement on an unrelated issue.” Each displayed piece of work undergoes thorough examination before being accepted by the curatorial committee. Despite this procedure, the Karachi Biennale Team has distanced themselves from the artist. Karachi Biennale’s Team’s position values the so-called apolitical and finds it acceptable to silence the stories of 444 residents of Karachi who have died at the hands of the city’s establishment. Art is inherently political, as is the use of public space, and cultural discourse. The Biennale Team has lost a golden opportunity to stand up against those that suppress democracy and freedom of speech. Karachi is poorer for this.

A press conference was organised on October 27 by Jibran Nasir. It was interrupted by Director General Karachi Municipal Corporation Park’s Division Afaq Mirza who felt that Adeela Suleman’s art is vandalism (it appears he is the arbiter on what constitutes art) and instead art must be used to promote a positive image of Pakistan. This toxic thinking tells us to focus on Kashmir, focus on external enemies, on everything but the rot that is in our society. “I’m not saying Rao Anwar is a good man, he’s a number one murderer,” DG Parks said, “but on Kashmir Day, permission was given to depict artwork and culture. Instead, they took it as an opportunity to educate people about Rao Anwar and Naqeebullah and said so many people have been killed by him [Anwar].” The citizens of Karachi have been told: this is not the time to educate people about the injustice in our society. This incident demonstrates that art is only acceptable if it is uncontroversial, pro-establishment, and protective of oppressors. It is not a part of art or our culture to subvert the status quo. If we live in a time of uncritical expression, a petulant establishment, and a subservient intelligentsia, there is little hope for Pakistan.

The Biennale’s overall contribution to Karachi should be recognised. It is difficult to achieve a wide level of engagement without the Government’s acceptance, and security considerations are a reality. However, if the mission was to work towards the public interest, the public interest is not advanced by hiding behind curatorial selection and thematic preferences. It is time for those associated with the Karachi Biennale to investigate the matter, engage in damage control, and begin a discourse based on the truth. For now, the conversations that matter have once again been pushed from the public space into the private sphere. An opportune moment to do things differently, in the open, has tragically been lost and Karachi is a darker place because of it.

The writer is a barrister, PhD candidate in criminology at the University of Cambridge, and consultant for UN agencies in Vienna and Beirut