“People were pouring in from both sides, and piling on top of one another. One moment, I had enough room to extend both arms, and the next, I was in a human vise, unable to breathe and unable to move, in blind panic,” says Salahuddin, who survived a Hajj stampede during the ritual stoning of Satan in 1991. “The mob pushed me against the fence on one side, I managed to grab one of the bars and pull myself close to it. I pushed my head through the bars and could finally breathe.”

According to the latest figures released by the Saudi health minister, at least 1,100 people have lost their lives in the horrific stampede during the Hajj pilgrimage in Saudi Arabia this year. At least 42 of them were of Pakistani origin.

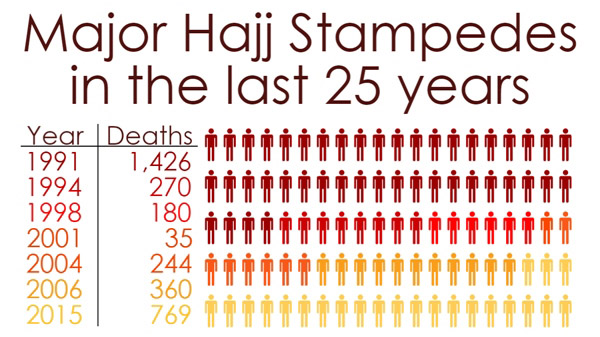

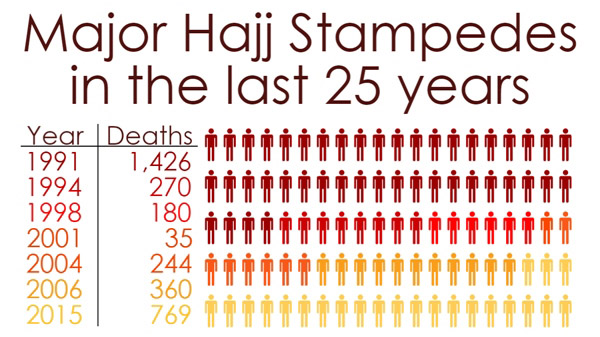

Although this was the deadliest stampede in over two decades, stampedes and associated deaths are a common trait of the annual event. Edbert Hsu at John Hopkins School of Medicine conducted a study of stampedes in 2010. According to his research, 215 human stampedes occurred between 1980 and 2010, resulting in 7,000 deaths and 14,000 injuries. If the figure is accurate, over a third of these deaths, or nearly 36%, have resulted from six major stampedes during Hajj.

Every year, nearly two million Muslims congregate in Mecca, Mina, Arafat, and Muzalfah for the various stages of the pilgrimage, completed over four days. This influx of pilgrims obviously presents a range of operational and logistical challenges for the Saudi administration, officially responsible for the upkeep and management of the holy sites.

“Back then, there was no management to speak of. We were provided no facilities, no bathrooms; people would defecate and urinate wherever they could find the space. At night, even at the doors of Mosque Al-Khaif, it would be pitch-black.” Salahuddin seems visibly upset, and shudders as he recalls the stampede he had witnessed. “That day when we entered the bridge to stone Satan, two groups collided. There were no signs directing traffic and no officials to guide us. It was just one giant mess. Once the stampede began, you had no control over the direction you were moving in, like a ragdoll, just getting tossed around in a sea of people.”

Stampedes do not occur spontaneously. They have identifiable triggers. Salahuddin’s account echoes John Seabrook’s 2011 work on the causes of stampedes. Nearly always, something stops the flow of traffic: a closed exit, another group moving in a different direction, someone stumbling and causing a pileup, failed ventilation, etc. Space reduces rapidly, until you are pinned in a mass of bodies, unable to breathe, move, or even lift your arms, often swept literally off of your feet. This is called a “crowd crush”, often resulting in a domino effect, where people pile atop one another. Those at the bottom have next to no chance of survival, those at the top may live, as long as their airway isn’t blocked and their lungs are not crushed. In short, stampedes do not start at the behest of one member of an unruly crowd, they have a precipitating factor. And regardless of the cause, once they begin, they are violent, deadly and uncontrollable.

The most deadly Hajj stampede in 1991, that claimed 1,426 lives, began because the ventilation system broke down in a tunnel, causing suffocation and panic.

The trigger this year, many pilgrims recall, was a roadblock by the police, resulting in a pileup of pilgrims. The police allegedly blocked all roads except one. The crowd, travelling in both directions, funneled into this route, causing severe blockage. In the blistering heat of the Arabian Desert, thousands were packed into a small space, traveling in opposite directions. Temperatures soared and panic ensued, and at the point that these two mobs met, the stampede occurred. The roadblock, some witnesses claim, was put in place to allow some dignitaries to pass through. They blame the Saudi government for creating the roadblock that led to the stampede.

Salahuddin remembers being grated against the fence in one direction as he held on to one bar after another to maintain some sense of where he was. “I dropped everything. My bottle of water, my shoes, my umbrella, my towel, I had barely any idea where I was, let alone my belongings. Eventually, the pressure subsided, and I mounted the fence and jumped off of the bridge. I was in my thirties back then, and I fell 10 feet or so. I remember just panting on the ground for a few minutes, thanking Allah I was alive. The pouch around my waist had torn and most of the contents were missing. I found a 10 Riyal note. I bought slippers from a roadside vendor for two, and tetra-packets of juice with the rest from a vendor on a trailer. Then I sat on the side of the trailer with the shade, drank the juice and cried. To this day, I don’t know how I survived.”

The author is a journalist and a Senior Research Fellow at the Center for Research and Security Studies in Islamabad. He has a Master’s degree in strategic communications from Ithaca College, NY.

Email: zeeshan[dot]salahuddin[at]gmail.com

Twitter: @zeesalahuddin

According to the latest figures released by the Saudi health minister, at least 1,100 people have lost their lives in the horrific stampede during the Hajj pilgrimage in Saudi Arabia this year. At least 42 of them were of Pakistani origin.

Although this was the deadliest stampede in over two decades, stampedes and associated deaths are a common trait of the annual event. Edbert Hsu at John Hopkins School of Medicine conducted a study of stampedes in 2010. According to his research, 215 human stampedes occurred between 1980 and 2010, resulting in 7,000 deaths and 14,000 injuries. If the figure is accurate, over a third of these deaths, or nearly 36%, have resulted from six major stampedes during Hajj.

Every year, nearly two million Muslims congregate in Mecca, Mina, Arafat, and Muzalfah for the various stages of the pilgrimage, completed over four days. This influx of pilgrims obviously presents a range of operational and logistical challenges for the Saudi administration, officially responsible for the upkeep and management of the holy sites.

“Back then, there was no management to speak of. We were provided no facilities, no bathrooms; people would defecate and urinate wherever they could find the space. At night, even at the doors of Mosque Al-Khaif, it would be pitch-black.” Salahuddin seems visibly upset, and shudders as he recalls the stampede he had witnessed. “That day when we entered the bridge to stone Satan, two groups collided. There were no signs directing traffic and no officials to guide us. It was just one giant mess. Once the stampede began, you had no control over the direction you were moving in, like a ragdoll, just getting tossed around in a sea of people.”

‘I was in a human vise, unable to breathe and unable to move’

Stampedes do not occur spontaneously. They have identifiable triggers. Salahuddin’s account echoes John Seabrook’s 2011 work on the causes of stampedes. Nearly always, something stops the flow of traffic: a closed exit, another group moving in a different direction, someone stumbling and causing a pileup, failed ventilation, etc. Space reduces rapidly, until you are pinned in a mass of bodies, unable to breathe, move, or even lift your arms, often swept literally off of your feet. This is called a “crowd crush”, often resulting in a domino effect, where people pile atop one another. Those at the bottom have next to no chance of survival, those at the top may live, as long as their airway isn’t blocked and their lungs are not crushed. In short, stampedes do not start at the behest of one member of an unruly crowd, they have a precipitating factor. And regardless of the cause, once they begin, they are violent, deadly and uncontrollable.

The most deadly Hajj stampede in 1991, that claimed 1,426 lives, began because the ventilation system broke down in a tunnel, causing suffocation and panic.

Stampedes do not occur spontaneously. They have identifiable triggers

The trigger this year, many pilgrims recall, was a roadblock by the police, resulting in a pileup of pilgrims. The police allegedly blocked all roads except one. The crowd, travelling in both directions, funneled into this route, causing severe blockage. In the blistering heat of the Arabian Desert, thousands were packed into a small space, traveling in opposite directions. Temperatures soared and panic ensued, and at the point that these two mobs met, the stampede occurred. The roadblock, some witnesses claim, was put in place to allow some dignitaries to pass through. They blame the Saudi government for creating the roadblock that led to the stampede.

Salahuddin remembers being grated against the fence in one direction as he held on to one bar after another to maintain some sense of where he was. “I dropped everything. My bottle of water, my shoes, my umbrella, my towel, I had barely any idea where I was, let alone my belongings. Eventually, the pressure subsided, and I mounted the fence and jumped off of the bridge. I was in my thirties back then, and I fell 10 feet or so. I remember just panting on the ground for a few minutes, thanking Allah I was alive. The pouch around my waist had torn and most of the contents were missing. I found a 10 Riyal note. I bought slippers from a roadside vendor for two, and tetra-packets of juice with the rest from a vendor on a trailer. Then I sat on the side of the trailer with the shade, drank the juice and cried. To this day, I don’t know how I survived.”

The author is a journalist and a Senior Research Fellow at the Center for Research and Security Studies in Islamabad. He has a Master’s degree in strategic communications from Ithaca College, NY.

Email: zeeshan[dot]salahuddin[at]gmail.com

Twitter: @zeesalahuddin