Following street demonstrations protesting fee hikes in private schools, the government has announced a freeze on private school fees. Financially strapped parents are no doubt pleased. But this step is no more than a bandaid. It doesn’t begin to get to the problem of how to ensure a proper education for Pakistan’s huge population of young people.

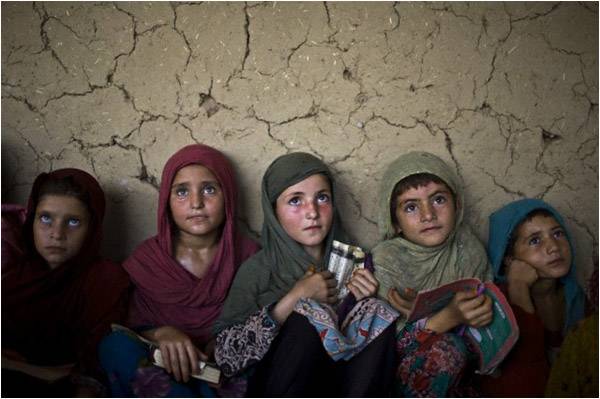

By virtually any measure, Pakistan’s education system is in trouble. In a recent report prepared for UNESCO, Pakistan ranked 106th out of 113 countries for which data was available. The country’s education system is plagued by wide regional, urban-rural, income, language, and gender disparities. It suffers from overcrowded classrooms, poorly trained, unmotivated, or absentee teachers, inadequate and sometimes inaccurate curricula, inferior and in many cases non-existent physical facilities, and poor monitoring and assessment mechanisms.

None of these shortcomings can be tackled unless Pakistan decides to get serious about addressing its education deficiencies. And that will take money, more than this government—or any of its predecessors—have been prepared to spend.

In its 2009 National Education Policy report, the Ministry of Education called for the country to increase its spending on education from the then 2.7 percent of GDP to 7 percent by 2015—a recommendation that has been roundly ignored in the years since. Since then, things have moved in the wrong direction. The Ministry of Finance’s Pakistan Economic Survey 2014-15 reported that public spending on education in 2013-14 was a paltry 2.14 percent of GDP, comparable to Bangladesh’s 2.1 percent, but substantially lower than the 3.2 percent in India and 4.7 percent in Iran.

Precise figures vary from survey to survey, but the bottom line conclusion remains constant: Pakistan is losing ground to its neighbors in the battle to prepare its young people to meet the challenges of the 21st century. According to the US Central Intelligence Agency, in 2013 Pakistan ranked 164th (out of 173 countries) in the world in education expenditures as a percentage of GDP. All its large neighbors ranked higher: Iran was 119th, India 134th, and Bangladesh 161st.

Nor is the spending that does take place oriented toward investing in the future. The majority of current expenditures go to salaries. Relatively little is set aside for teacher training, curriculum development, upgrading of school facilities, monitoring, assessment, and supervision, and other quality enhancements that would produce benefits year after year.

The election of May 2013 brought in a new government with a sizable majority and a clear mandate for moving the country into a higher gear. Politicians and experts alike recognized that reforms in the education sector were needed to fuel this demand for change. At the July 2015 Oslo Summit on Education and Development, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif pledged that his government will increase education spending to 4 percent of GDP.

Meeting this target will be tough. Final numbers for the 2015-16 budget are not yet available, but the underlying reality will no doubt remain the same: Pakistan greatly underspends on education in comparison to its neighbors, other countries of its size, and the developing world generally.

The country’s narrow tax base helps to explain this underspending; Pakistan’s tax-to-GDP ratio, below 10 percent, is among the lowest in the world. Of course this narrow tax base is a reflection of an even more fundamental reason for Pakistan’s failure to spend more on education: an absence of political will among the country’s ruling elite.

The ordering of national priorities also has a significant impact. In 2001, at a time when Pakistan’s military spending was considerably lower than it is today, developmental economist William Easterly argued that Pakistan’s overspending on defense (compared with other countries at similar income levels) was roughly equal to the country’s underspending on education and other social services. Today the mismatch between military and education expenditures is even greater.

Malala Yousafzai, the Pakistani schoolgirl nearly killed by the Taliban for her advocacy of girls’ education, recently told a Pakistani TV channel that Prime Minister Sharif had confessed to her that he was unable to spend more on education because of pressure to fund military operations. (The television station edited out the girl’s remark for fear of causing offense.)

A study published in 2010 found that in Punjab, parents were paying more than half of their children’s educational expenditures, even though public schools are ostensibly free. Tuition charges and uniform, textbook, and other fees, as well as opportunity costs incurred once children can contribute to the family income, all encourage higher out-of-school and lower retention rates, especially for children from poor families.

Economic constraints frequently lead families to choose sending their sons to school rather than their daughters. This is ironic (and counterproductive), since a 2009 analysis calculated that an additional year of education produces 13-18 percent returns for women, but only 7-11 percent for men. In other words, females have significantly greater economic incentives to remain in school than males.

Since the 2010 adoption of the 18th Amendment, the State is obligated to provide free and compulsory education to all children up to 16 years old. The same amendment, of course, also devolved many of the federal government’s responsibilities, including those in the field of education, to the provinces. Devolution, however, did not relieve the central government of all obligations in this area, because of the constitution’s guarantee of free and compulsory education.

Every year the federal government provides provinces with funds for education; provinces can also generate their own revenue through various taxes. (Typically, transfers from the federal government comprise about 90 percent of total provincial income.) But neither the federal nor the provincial governments have been willing to raise the amount of funding required to meet the country’s education needs.

This may not matter much; the provincial education departments possess limited institutional capacity to design, manage, and implement programs and budgets. Remarkably, Pakistan does not spend a sizable proportion, upwards of 20 percent in some years, of the funds annually allocated for education, in part because of weaknesses in planning capacity and accountability mechanisms.

Pakistan’s youth bulge can be either a life line or a liability. That will be determined, in good measure, by whether Pakistan is able to give its young people decent schooling. Education is one of the most powerful instruments for increasing labor productivity, raising incomes, and reducing poverty. A quality education fosters the creativity, innovation, and entrepreneurship essential for success in today’s economy.

Moreover, the possession of basic reading, writing, and numeracy skills correlates with improved health, a lower fertility rate, smaller families, and greater gender equality, and contributes to a virtuous cycle that extends to future generations. Education can be an empowering agent for the people of Pakistan.

But only if Pakistan is prepared to spend the money needed to give its youth a solid education. And only if it is willing to make the hard choices required to spend these monies wisely.

To be sure, Pakistan is a poor country facing great competition for limited budgetary resources from many worthy claimants. But so are many of its neighbors, who nonetheless have provided their education sectors with a greater share of their nation’s financial resources. Financial austerity cannot excuse deliberate education self-impoverishment.

Robert M Hathaway is a Public Policy Fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington and, most recently, co-editor of New Security Challenges in Asia

By virtually any measure, Pakistan’s education system is in trouble. In a recent report prepared for UNESCO, Pakistan ranked 106th out of 113 countries for which data was available. The country’s education system is plagued by wide regional, urban-rural, income, language, and gender disparities. It suffers from overcrowded classrooms, poorly trained, unmotivated, or absentee teachers, inadequate and sometimes inaccurate curricula, inferior and in many cases non-existent physical facilities, and poor monitoring and assessment mechanisms.

None of these shortcomings can be tackled unless Pakistan decides to get serious about addressing its education deficiencies. And that will take money, more than this government—or any of its predecessors—have been prepared to spend.

Pakistan is losing ground to its neighbors in the battle to prepare its young people to meet modern challenges

In its 2009 National Education Policy report, the Ministry of Education called for the country to increase its spending on education from the then 2.7 percent of GDP to 7 percent by 2015—a recommendation that has been roundly ignored in the years since. Since then, things have moved in the wrong direction. The Ministry of Finance’s Pakistan Economic Survey 2014-15 reported that public spending on education in 2013-14 was a paltry 2.14 percent of GDP, comparable to Bangladesh’s 2.1 percent, but substantially lower than the 3.2 percent in India and 4.7 percent in Iran.

Precise figures vary from survey to survey, but the bottom line conclusion remains constant: Pakistan is losing ground to its neighbors in the battle to prepare its young people to meet the challenges of the 21st century. According to the US Central Intelligence Agency, in 2013 Pakistan ranked 164th (out of 173 countries) in the world in education expenditures as a percentage of GDP. All its large neighbors ranked higher: Iran was 119th, India 134th, and Bangladesh 161st.

Nor is the spending that does take place oriented toward investing in the future. The majority of current expenditures go to salaries. Relatively little is set aside for teacher training, curriculum development, upgrading of school facilities, monitoring, assessment, and supervision, and other quality enhancements that would produce benefits year after year.

The election of May 2013 brought in a new government with a sizable majority and a clear mandate for moving the country into a higher gear. Politicians and experts alike recognized that reforms in the education sector were needed to fuel this demand for change. At the July 2015 Oslo Summit on Education and Development, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif pledged that his government will increase education spending to 4 percent of GDP.

Meeting this target will be tough. Final numbers for the 2015-16 budget are not yet available, but the underlying reality will no doubt remain the same: Pakistan greatly underspends on education in comparison to its neighbors, other countries of its size, and the developing world generally.

The country’s narrow tax base helps to explain this underspending; Pakistan’s tax-to-GDP ratio, below 10 percent, is among the lowest in the world. Of course this narrow tax base is a reflection of an even more fundamental reason for Pakistan’s failure to spend more on education: an absence of political will among the country’s ruling elite.

The ordering of national priorities also has a significant impact. In 2001, at a time when Pakistan’s military spending was considerably lower than it is today, developmental economist William Easterly argued that Pakistan’s overspending on defense (compared with other countries at similar income levels) was roughly equal to the country’s underspending on education and other social services. Today the mismatch between military and education expenditures is even greater.

Malala Yousafzai, the Pakistani schoolgirl nearly killed by the Taliban for her advocacy of girls’ education, recently told a Pakistani TV channel that Prime Minister Sharif had confessed to her that he was unable to spend more on education because of pressure to fund military operations. (The television station edited out the girl’s remark for fear of causing offense.)

A study published in 2010 found that in Punjab, parents were paying more than half of their children’s educational expenditures, even though public schools are ostensibly free. Tuition charges and uniform, textbook, and other fees, as well as opportunity costs incurred once children can contribute to the family income, all encourage higher out-of-school and lower retention rates, especially for children from poor families.

Economic constraints frequently lead families to choose sending their sons to school rather than their daughters. This is ironic (and counterproductive), since a 2009 analysis calculated that an additional year of education produces 13-18 percent returns for women, but only 7-11 percent for men. In other words, females have significantly greater economic incentives to remain in school than males.

Since the 2010 adoption of the 18th Amendment, the State is obligated to provide free and compulsory education to all children up to 16 years old. The same amendment, of course, also devolved many of the federal government’s responsibilities, including those in the field of education, to the provinces. Devolution, however, did not relieve the central government of all obligations in this area, because of the constitution’s guarantee of free and compulsory education.

Every year the federal government provides provinces with funds for education; provinces can also generate their own revenue through various taxes. (Typically, transfers from the federal government comprise about 90 percent of total provincial income.) But neither the federal nor the provincial governments have been willing to raise the amount of funding required to meet the country’s education needs.

This may not matter much; the provincial education departments possess limited institutional capacity to design, manage, and implement programs and budgets. Remarkably, Pakistan does not spend a sizable proportion, upwards of 20 percent in some years, of the funds annually allocated for education, in part because of weaknesses in planning capacity and accountability mechanisms.

Pakistan’s youth bulge can be either a life line or a liability. That will be determined, in good measure, by whether Pakistan is able to give its young people decent schooling. Education is one of the most powerful instruments for increasing labor productivity, raising incomes, and reducing poverty. A quality education fosters the creativity, innovation, and entrepreneurship essential for success in today’s economy.

Moreover, the possession of basic reading, writing, and numeracy skills correlates with improved health, a lower fertility rate, smaller families, and greater gender equality, and contributes to a virtuous cycle that extends to future generations. Education can be an empowering agent for the people of Pakistan.

But only if Pakistan is prepared to spend the money needed to give its youth a solid education. And only if it is willing to make the hard choices required to spend these monies wisely.

To be sure, Pakistan is a poor country facing great competition for limited budgetary resources from many worthy claimants. But so are many of its neighbors, who nonetheless have provided their education sectors with a greater share of their nation’s financial resources. Financial austerity cannot excuse deliberate education self-impoverishment.

Robert M Hathaway is a Public Policy Fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington and, most recently, co-editor of New Security Challenges in Asia