“I never imagined a dance without imagining who was dancing it,” Eliot Feld.

Dance, the kinetic affirmation of being alive, is an integral part of most cultures. For some, it is the forum through which society functions: history is passed on, lovers are courted and people are healed. In our culture – at least on the concert dance stage – these facets are sometimes overlooked and categorisations of style, body type, gender and race frequently come into play. A dance artist might well encounter these issues in the course of his or her career. Although individual dancers will interpret a role in their own way, the dance artist remains a conduit for the choreographer’s vision – expressing a multitude of themes and emotions created by someone else. But who, exactly, is this person who communicates with the world through the silent language of dance? And what experiences have helped to shape him?

The “male” question is only part of a larger question. For me, it is about how one expresses the multidimensional representation of what “male” or “female” mean. Navtej Singh Johar – nicknamed “the dancing sardar” by the late Khushwant Singh – has very consciously set out to cultivate a world rich in nuances where gradations of difference between male and female are the stuff of poetry. But on the question of differences, perhaps there is sometimes a bit more presumption in the way a man occupies a space? I am speaking in generalities here, but men behave as if the space were theirs to be claimed and commanded. Men often start to practice dance later and have less freedom in society to express themselves lyrically through movement. A young boy has to have an extraordinary support system – and a very strong personality – to survive in the dance world. Dance, for men, is somewhat suspect terrain and separates them from the majority of the male population. This is a filtering system, it seems, and only certain individuals can survive it.

A young boy has to have a very strong personality to survive in the dance world

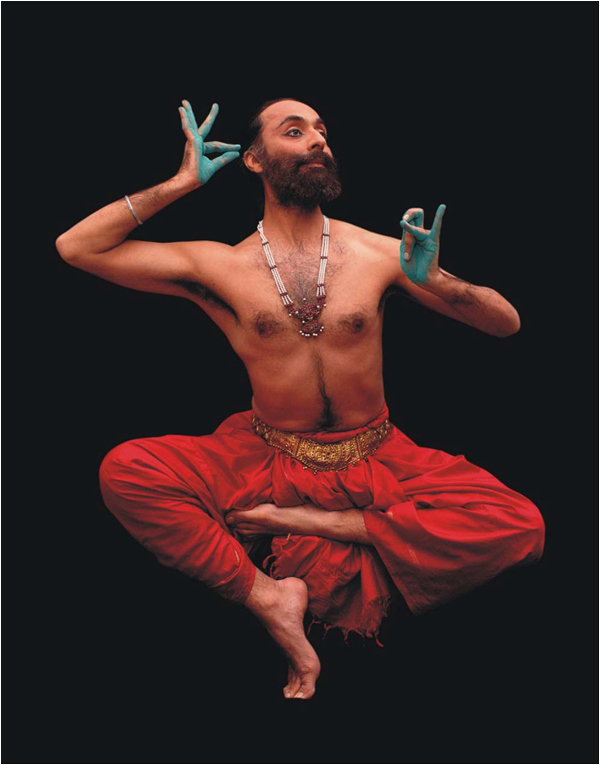

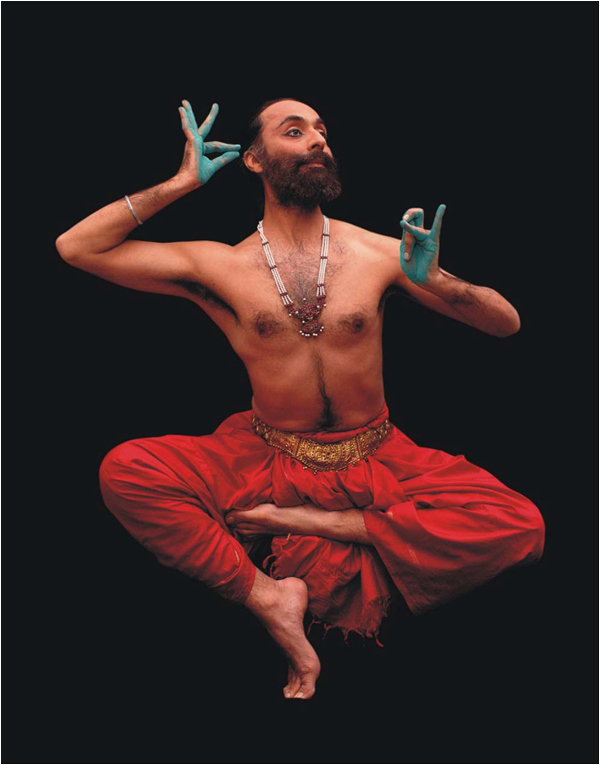

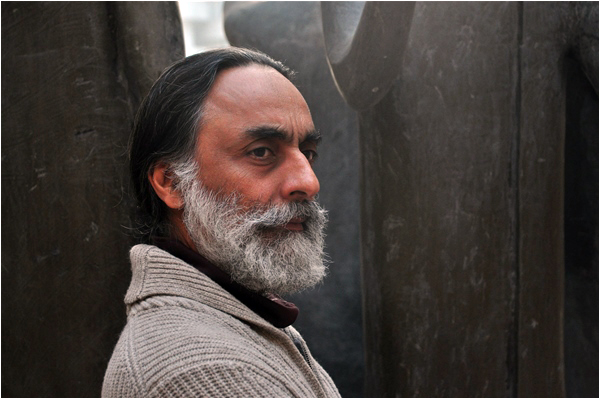

Navtej Singh Johar is one of the world’s most refined exponents of Bharatanatyam and a modern choreographer. Trained at Kalakshetra in Madras and at Shriram Bharatiya Kala Kendra in New Delhi, he later studied at the Department of Performance Studies in New York. He has collaborated with Stephen Rush and Shubha Mudgal, with visual artist Shebha Chachi, and acted in films such as Sabiha Sumar’s Khamosh Pani and Deepa Mehta’s Earth.

A long-time student and practitioner of yoga, Johar trained in Patanjali yoga at Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram in Madras. A yoga trainer since 1985, he founded the Studio Abhyas in 2001 in New Delhi and the Abhyas Trust in 2004, which is dedicated to yoga, dance, urban design and the care of stray animals. Johar is widely travelled and has conducted workshops, lectured and performed all across the globe. In 1996, he received a Times of India Fellowship to research the sociopolitical history of Bharatanatyam, followed by a Charles Wallace Fellowship in 2000, a Michigan State University Residency in 2001, and the Sri Krishna Gana Sabha Award.

As part of the International Dance Festival held at the PNCA in Islamabad in December 2014, organised by Sadaan Peerzada of the Rafi Peer Theatre Workshop, Johar mesmerised his audience with a rendition of Meenakshi Memudam Dehi – a Dikshitar kriti – set to Raga Purvikalyani and Adi Talam. It was a melodic gem with vocals by G. Elangovan and accompanied by the violin, nattuvangam and mridangam. The artiste drew a comparison between the full moon and moon-faced Meenakshi to spellbinding effect.

"People persuaded me to pursue dance because I 'had a dancer's demeanour'"

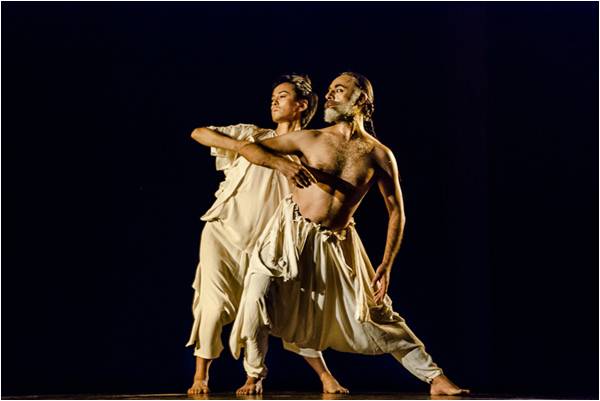

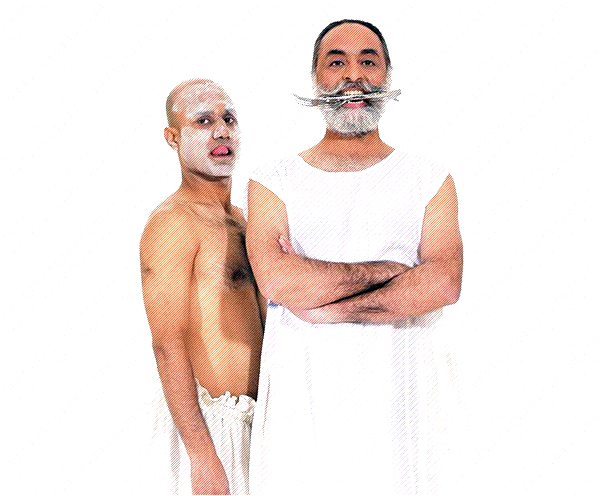

The piece to follow, perhaps a variation on Fanaa: Ranjha Revisited, was rendered by Johar in collaboration with Naheed Siddiqui. Set to vocals by Tufail Niazi (“Ranjha jogara ban aaya”) in Raga Marwa, it was a brilliantly conceived, directed and choreographed piece-de-resistance that melded Bharatanatyam and Kathak with a potent dose of stylisation – what Johar referred to as the “Punjabi ang.”

Apart from the obvious – Johar is tall, attractively thin, with long, expressive limbs, a graceful neck, and a face Rembrandt would dream of painting – the wisdom of what he conveys onstage seems positively preternatural. Flickering memories of past maestros come to mind: the joyous musical phrasing and innocence of young dancers; an elongated, eloquent torso similar to Balanchine; and a mysterious allure uncannily reminiscent of Kelucharan Mohapatra. Beyond a rare coupling of vulnerability and technical confidence, Johar allows his sixth sense of the dance’s dramatic subtext to shine through.

I spoke to Johar between rehearsals in the quiet of the PNCA foyer:

AA: What propelled you to take up dance professionally?

NSJ: I come from a Punjabi Sikh background – my mother was from Rawalpindi and my father from Chakwal. Both the Punjabs (east and west) share the same ethos. For example, we share the same definition of gender roles and similar ideas pertaining to gender behaviour and so forth. I come from a background where, in pre-television days, dance had never been seen. The only dance I had seen, however, was in films – something to which I was never attracted.

When I was in school, I realised I was artistically inclined. (In those days, being artistically inclined meant you would go for art, namely painting.) So, I decided to paint but while I was painting, it dawned on me that there was “something” more visceral in me that needed to be expressed. (I didn’t tell my parents because they wouldn’t have allowed it.) This led to joining a theatre group, which I enjoyed immensely. People thought I was a good actor, which helped me realise there was “something” performative in me. But after having done theatre for quite a while, it began to bore me: it was too verbose for sustained interest; you had to talk too much! I felt like expressing myself through my body. My body was not athletic enough in the normal sense of the word, at that point. I didn’t play sports but something in me wanted to come out in movement. So I began to explore movement and realised that, what I had been coveting, was the chance to express myself through a vocabulary that was nonliteral, nonverbal and lyrical. People who I respected tremendously persuaded me to pursue dance because I “had a dancer’s demeanour.”

"Bharatanatyam is geometric: it is as distant from a natural dancer’s body as you can get"

That’s when I started to dream of becoming a dancer. After having dabbled in painting and theatre, it was almost through a process of elimination that I came to dance, performance being a physical act. It was by sheer coincidence that I saw my first performance of Bharatanatyam around that time.

AA: What was your first experience of Kalakshetra?

NSJ: The first performance of Bharatanatyam I saw in Chandigarh was by Padma Subramaniam. She performed Krishnaya Tubhyam Namaya. I instantly made up my mind that this was what I wanted to do, but there was a gradual build-up towards it. I was already “looking out”, smitten by dance. I decided to take a trip to Madras, on the quiet, to check the place out. Kalakshetra turned out to be a beautiful school by the sea: the beach, thatched roofs, animals running around and lily ponds – I fell in love with its simplicity.

However, the training was very rigorous: we would have a morning class on the theory of music, a class of hastas and abhinayas, followed by a two-and-a-half-hour-long dance class. After lunch, there would be another class till about four. In the evening, we were supposed to practice on our own. There was a lot of emphasis on technique – both form and formality. Rukmini Devi Arundale founded Kalakshetra in 1935 on the premises of the Theosophical Society. Devi was Dr Annie Besant’s protégé and was encouraged by her to save the art form (already on the brink of extinction) from dying out. Devi took it upon herself to preserve the art form while censoring it so that it did not have the bearings of the devadasi style, which was more erotic and amorous. There was a conscious effort to shift its focus from the erotic to the spiritual. That created a divide between the two, which, in actuality, did not exist.

It was rigorous because the format had to be perfect. The kind of pieces that you would choose and the kind of gestures you would make were not just about training, but also about conditioning, self-editing and self-selection. Since it was all under the umbrella of the Theosophical Society, there was an aura of philosophy surrounding it. It wasn’t quite like any other dance school. Whatever the society symbolised, it percolated down to spirituality and a novel idea of India. Besant was president of the National Congress then. The whole notion of a national heritage and national art had begun to emerge.

AA: How would you compare it to Leela Samson’s Shriram Bharatiya Kala Kendra in Delhi?

NSJ: Leela’s style was a little more explorative because she was much younger. On the other hand, as a product of Kalakshetra, she had the same sensibility even though she was slightly more innovative and “current”, but not necessarily contemporary. I chose Bharatanatyam for the sheer formalism of it. It has a formal technique, which is, of course, beautiful but the expression that defines it best is “geometric”. Kathak is more earth-bound: you can start dancing while standing and its form is not so different from that of a pedestrian dancer. Bharatanatyam, on the contrary, is iconographic. It has an iconised form – as distant from a natural dancer’s body as they get. I was attracted by the stylisation – the form and the technique – and it was the impact of the form that I loved. I was also intrigued by the accompanying music. The image that it conjured up was larger than life. It was a form I thought would sit well on a male body, as opposed to Odissi and Mohiniattam. It was both vigorous and rigorous.

"I collaborate to break free of formulae"

AA: What made you move on to the Centre of Performing Arts in New York City? Were you trying to look at dance from yet another angle in order to gain a fresh perspective?

NSJ: It was force of circumstance that took me to New York. I had begun to realise that, having moved into dance from theatre, I already had a very clear idea of what performance had come to mean to me. When I ventured into dance, it became a performing vocabulary, and now I wanted to look at dance from a “performance art” perspective. In addition, I had a lot of questions and a lot of problems with dance and its politics, mainly with its being a national showcase in India apart from the divide that was created to redefine its journey from the erotic to the sacred. This divide never sat well with me and I was never comfortable with these divisions. In order to delve deeper into questions that dancers and/or the dance milieu had not been able to answer (let alone address), I realised I had to approach dance from another point of view.

Performance studies at the Centre were strictly anthropological, based on the cultural anthropology of dance vis-à-vis its historic evolution and significance in Indian/Hindu ritual. It was more of an academic inquiry. It helped me understand society’s need to perform. Why is performance inevitable? What are the different ways one can perform? How might society use performance as opposed to how a performer can change society? Why do people perform? Why are people not allowed to perform? Why are performances censored or used in a particular manner? It all boiled down pretty much to the same answer for each society. It depends on what age the performer lives in or what purpose a performance can serve, for example, if it is a shamanistic or prophylactic or a fertility rite – or more currently, national propaganda – or if it is a creative instinct.

AA: Where do you draw the line between classical, folk and tribal dance?

NSJ: It’s a sliding scale, and we can’t really divide the two. Such categories are all add-ons. They are constructs of the early 20th century. Folk music in the Punjab, for instance, is as rich, profound and technically varied as classical music. So, where lies the difference? It’s just that a folk singer’s way of training and methodology is different. Perhaps, folk is more rooted in the people, in the loci; it speaks from the people’s perspective and they are the masters of their own tradition. I am quite uncomfortable with the notion that the classical is ‘codified’. Very often, I mix the two, and you cannot tell the difference.

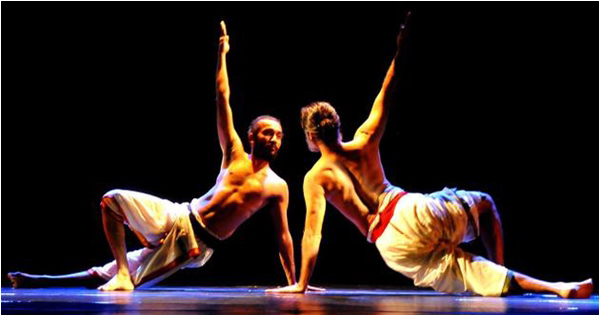

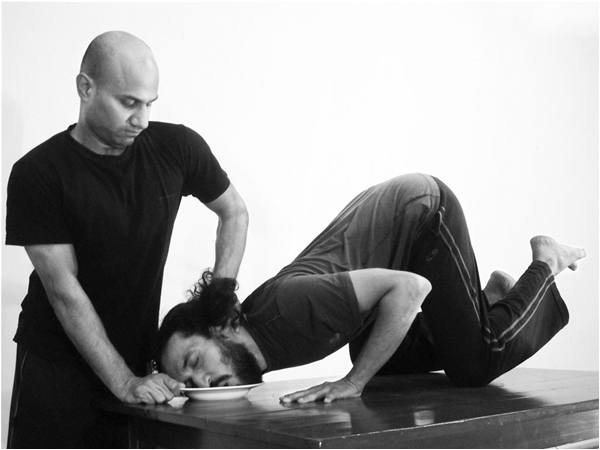

The person I sought to work with – who impressed me most – was Chandralekha because she turned the Indian dance tradition on its head. There’ve been others who’ve been very influential, but I would like to follow in Chandra’s footsteps and carry further her tradition of celebrating the indigenous Indian dance form while at the same time remaining radically opposed to almost all kinds of conventions. I consider her my mentor.

Talking about collaborations across borders, Stephen Rush, for example, is a musician and I am a dancer. He composed and I performed, and we had ideas about what we could make together. We began from scratch – I built up my dance vocabulary, he built up his music repertoire. We intermingled and kept discussing things with each other every step of the way.

There’ve been two kinds of collaboration so far: one in which people already had something in mind or a piece they wanted me to play a counterpart to, whether in movement, dance, image or music. From my point of view, there is always collaboration. It’s not that two people have to make something together. I feel that the way the other person works with another medium will elicit something from me – something that just plain dance cannot. For example, the way a painter or a sculptor works: the object of that painting or sculpture will inspire me and invoke something in me, but also the way an artist makes his work will challenge my methodology of dance. There’s a dialogue and an exchange between ways of making our work: the painter will paint like a dancer and the dancer will dance like a painter. These are the methodologies that facilitate creativity – otherwise it’s a formula. I collaborate to break free of formulae.

AA: What kind of a relationship exists between yoga and dance?

NSJ: In both, the body is the medium. Yet there is a conflict between the two: dance is extroverted whereas yoga is introverted. Initially, it’s not quite as easy to combine the two. Of course, yoga is very helpful for dance, but they are not as complementary as people make them out. Asana and pranayama are basic things that most yogis do, and I haven’t introduced anything new to it. These are traditional practices.

Patanjali authored the text Yoga sutras, which uses the body to still the mind. It’s considered deeply spiritual but without any divine intervention. You can have a sense of God, but it uses the body as a medium to achieve the highest depths of serenity.