On the other hand, Dr. Hameed Khan at the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP), Karachi, advocated another development model. It was based on some of his experiences. He derived some principles: to let people organise themselves, acquire new skills, form their capital, and establish links to external sources, particularly with the government officials. At those times, almost all development practitioners visited the OPP office, and preferred to have a meeting with Dr Akhtar Hameed Khan. This scribe, during his development carrier days met with Dr Khan. I still recall one day he talked about organic leadership and sustainability of the development projects. It was the second time that the word ‘organic’ was posed to me. However, in the 1980s, Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci’s term ‘organic intellectual’ was part of our political discussions. But Dr. Akhtar Hameed Khan’s context and reference were different. He related organic leadership with the continuity of the development initiatives, cost-effectiveness and multiplication. Most NGOs leaders eagerly heard him, but carried the donors’ finance-intensive ideas. Perhaps, they thought that they have an ‘ideal-solution’ for underdevelopment and social ailments.

These organic leaders sometimes lead and at other times follow their communities

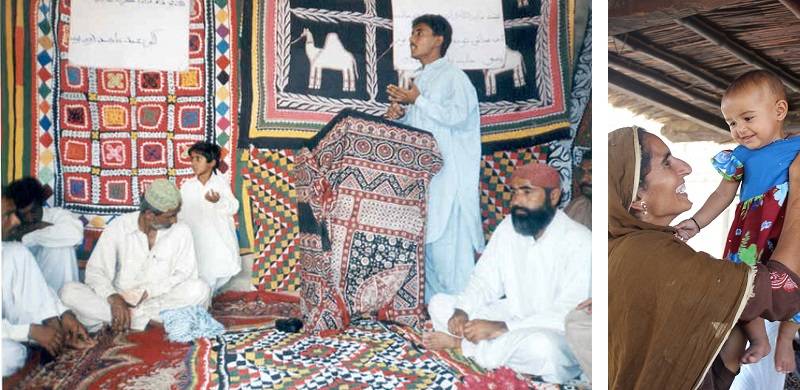

However, Mr Shoaib Sultan Khan truly practiced Dr Akhtar Hameed Khan’s ideas and spread them all over Pakistan. Over a period, Sindh, like other areas, proved a fertile ground for development ideas that sprouted from Dr. Khan’s practices. The big push came through the Sindh Union Council and Community Economic Strengthening Support (SUCCESS) Program. The European Union provided funds, and the Rural Support Program Network’s partners implemented it in Sindh. One of the official reports, dated 31st January, 2021, states that 29,920 community organisations were formed, and the number of village organisations was 3,444. Likewise, the number of local Support Organizations was 314,100.

The same report has focused on human development interventions. Figures reveal that 59,045 members were provided community related trainings, more than 8,100 members were trained in leadership skills and around 3,883 members were trained as community resource persons – capable of managing organizations’ financial transactions, as well as giving advice on legal and entrepreneurial issues.

This scribe invited Mr Nazar Joyo, a senior staff member of the National Rural Support Programme, to comment on the role of local leaders. He responded with some sentences as a preamble: that their leadership never derives power from a status or authority. “But these local leaders are the people who are deeply involved in solving community issues, who support in implementation, and their will and wisdom catalyse the local development process.” He added that local leaders have an unmatched position to put forward development ideas, stimulate villagers and create social impact. Moreover, these leaders in practice have learned the art of guiding communities. On the other hand, regular training, capacity-building initiatives and exposure have helped them to communicate a collective vision. Apart from all these factors, their emotional persuasiveness and conviction in development ideas has conditioned villagers to trust them.

These organic leaders sometimes lead and at other times follow their communities. In other words, in some situations, these leaders become followers and receive villagers’ suggestions, and simultaneously lead villagers to perform certain tasks. In this way, the organic leaders gain confidence, respect, and authority – that is earned and mutual – but that needs vigilance and uninterrupted renewal of the commitment.

In a short period of time, the interventions have inspired a new generation of local leaders and set in motion a ripple of change. However, capacity-building alone is not enough. A true dialogue among community leaders and the wider public is needed. Although, there are societal limitations, the prominent ones are the transitional nature of Sindhi society, and existing leadership model– the landowners – who are assisted by the federal government and the provincial government to be in power. Therefore, the latter group always captures local political power. Sindhi society, being hierarchical, adheres to particular traditional norms, one them is reverence toward the socially superior groups and those in power. As a result, even at the village level, political leadership is restricted to a few families. However, due to changes in society, the traditional style of leadership is no longer appropriate to meet the needs of the contemporary society in Sindh. Therefore, new set of skills is required to lead development projects, cater for political commitments, and network with leaders and institutions across the country.

Fortunately, the RSPN’s work has proved that local leaders are an untapped power in the national arena.

However, spread and replication of this homegrown leadership model needs a strong political will to open the prospect of leadership to a wider section of society.

Another factor that could play a part in creating a conducive environment for this organic leadership model is a genuine decentralisation of authority to local institutions. The field-based evidence shows that these leaders can create an endless chain of social change. This evolved organic leadership model is sound evidence for recommending to policy-makers, donors and the development community to scale up this successful leadership model.

Just imagine what a national network of organic leaders could achieve!

Dr. Zaffar Junejo has a Ph.D. in History from the University of Malaya. His areas of interest are post-colonial history, social history and peasants’ history. Presently, he is associated with Institute of Historical and Social Research, Karachi