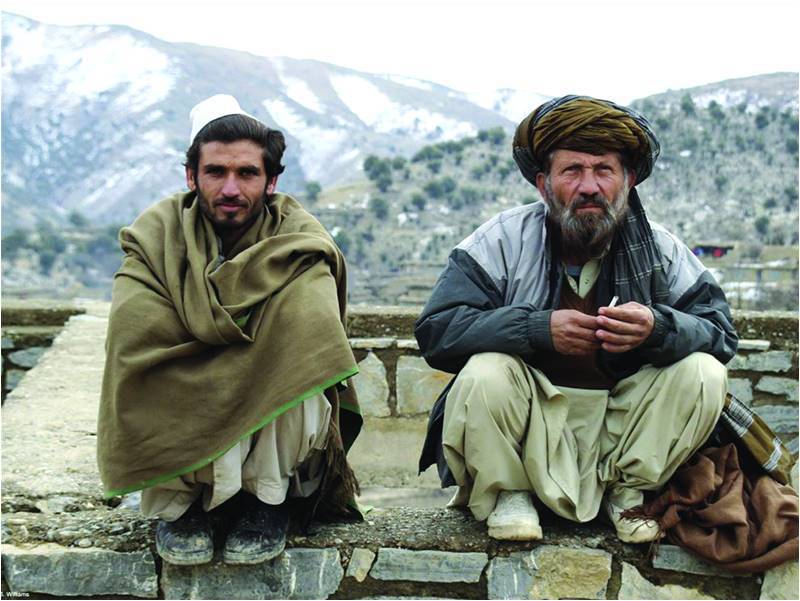

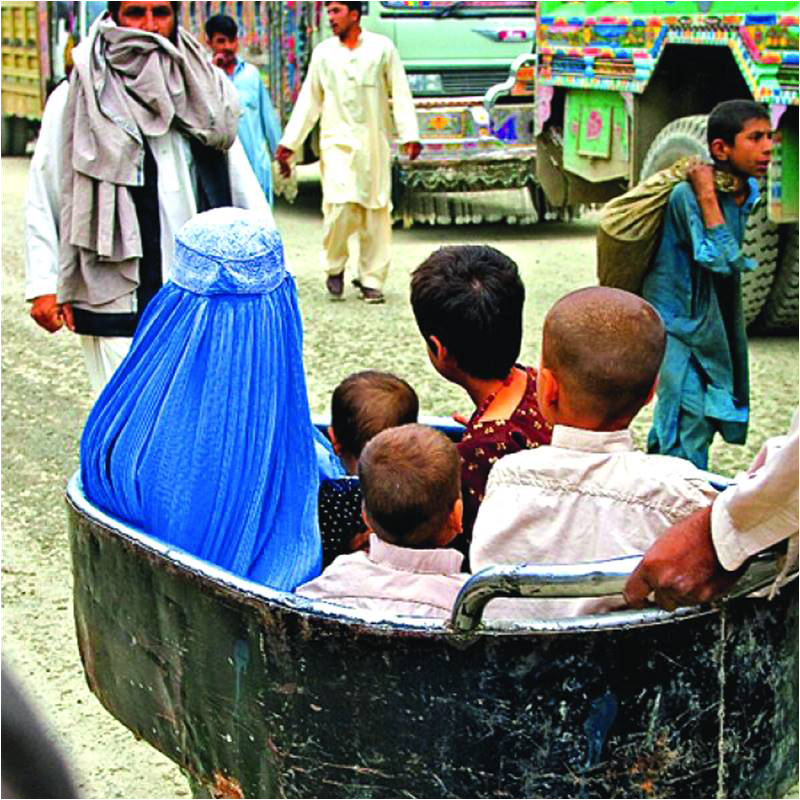

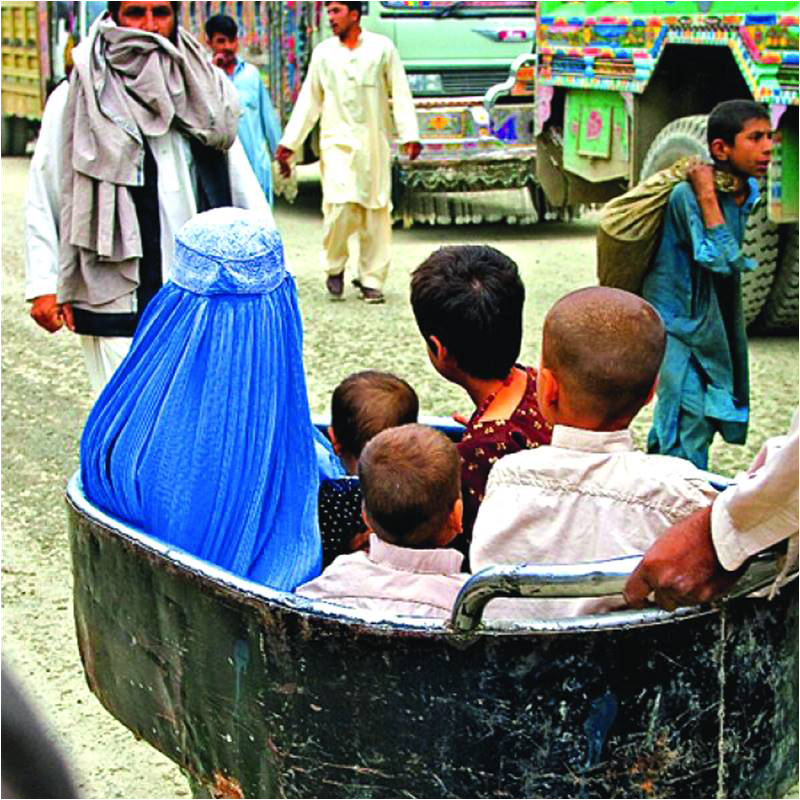

Recent news of the killing of two girls on the basis of “honour” in Waziristan, news of multiple incidents across Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa of domestic violence and the now-forgotten Kohistan video scandal all point to a particular violent and dehumanizing form of patriarchal violence in Pashtun society. Of course a very valid argument can be made that Pashtun society is just another patriarchal society and is part of the broader regional operation of patriarchal structures. It remains true that Pashtun culture is an extension of the broader tribal-patriarchal mindset and social structures, but there is a particular form of that tribal-patriarchy working in Pashtun lands, culture and society. The total absence of women from public spaces, the neurotic obsession with Purdah, the operation of a social order on the basis of a masculine honour which is defined through the guarding, regulating and expression of feminine bodies, voices and even the feminine form – all these are evidence enough of a particular form of patriarchal oppression in Pashtun society. This particular patriarchal oppression is justified through invoking archaic tribal codes, as well as the modernist neurosis about production of culture and nation through the bodies of women.

Imagining a Pashtun culture and nation, therefore, is not possible without rooting it in the particular role, place and status of women.

This is not to say that there is something inherently wrong in being a Pashtun or in Pashtun culture. Asserting that will be to essentialize a culture and a people - and thus will be reducing them to be nothing more than automatons whose behavior is determined by social structures which are timeless, and from the grip of which it is impossible to escape. All these particular social structures, attitudes and behaviors are the result of a historical and political conjuncture, and they can’t be understood without situating them in the historicity of the moment. Thus, they are neither eternal nor essential to a people. The identification of a people with rigid and dehumanizing social structures and attitudes is an epistemological violence which traps people in the ironclad prison of discourse and abstract the historical socio-political circumstances from determining the social form.

There have been two kinds of positions regrading this ossification of culture. The first one, as pointed out earlier, is a kind of essentialized celebration of culture which has been internalized by many Pashtuns and a significant part of Pashtun political consciousness and imagination. This one justifies the place of women, as we see it, through invoking Pakhtunwali or Pashtunwali, which is a medieval tribal code for social order and function of the Pashtun society. The other one accepts that there exists a particular oppression of women in Pashtun society but then their solution goes through the rabbit hole of prioritization, hierarchy and thus compartmentalization of struggle. The argument can be summarized as saying that “first we should solve the ‘national’ question and then after that we will solve the ‘woman’ question.” That argument is wrong on two counts, as it misunderstands both the national and the woman questions. By national question we mean here the resolution of the oppression which Pashtuns as the periphery face and how they as a whole people are produced as the ‘Other’ in the national imagination of Pakistan. The woman question may refer to a lot of things, but most important among them is the patriarchal structure of our domestic and public spaces, the participation of women in public spaces, equality of all genders in terms of opportunities and participation and of social acceptance that women can make their own choices and have full agency. That argument essentially also leads to fragmentation of struggles. The truth, both in theory and in praxis, lies between these two ossified positions, i.e. somewhere between stating that Pashtunwali has to be honoured and that the woman question can wait till the national question is solved.

I argue against both of these positions and towards an integrated conceptualization of the national and gender struggle which can lead to a broader articulation of integral struggles.

The argument from Pashtunwali is ahistorical as well as an ossification of imagination in a time past, thus disregarding the determinations and necessities of the social and political structures of the moment. Pashtunwali, in this age, is an archaic tribal code. In any case, Pashtunwali is an unwritten code which has many variants across the Pashtun lands and in some ways guides the social and cultural arrangements in Pashtun society. Though it does have its egalitarian precepts, many of its lived tenets make it an oppressive and misogynistic system. While every tribal society has its moral and legal tribal codes and they are developed in response to specific historical socio-political settings (and in turn may also define the socio-political settings), in case of Pashtunwali the problem arises when it is seen as an ideal or as a substrate for a political national consciousness. The aspects of Pashtunwali like Melmastia (hospitality), Hujra, Patt (honour in standing to the oppressor), Nanawatay (solving of disputes through intervention of elders or admitting your fault) are all egalitarian values and make Pashtunwali a code which ensured a social order and cohesion at certain times.

Having said that, the aspects of Pashtunwali which are not just incompatible with the precepts of human dignity but are downright oppressive. These would be the patriarchal and misogynist rooting of the meaning of social order and individual honour. Valwar (something like Vani), Ghag (announcing that you are going to marry that woman and thus no one else should try to be a suitor for her), Turr (allegation of impropriety on women), Purdah (a forced one at that) and violent conception of honour which is inseparably tied to the bodies and choices of women make Pashtunwali the de facto oppressive system for women in Pashtun society. The institutions of Jirga and Hujra which are touted as the evidence for social harmony of Pashtun society are all male-dominated spaces and work to exclude and erase women. They exclude women not only from leadership, but operate in ways that erase their very existence in public spaces. Pashtunwali is a tribal code which was born in an age of violence and thus it celebrates the violent masculine aspects in lived social reality rather than emphasizing the egalitarian social values.

The misogynist and patriarchal nature of the problem of application of Pashtunwali is compounded by the undue and uncritical celebration of it by some in nationalist quarters.

If Pashtunwali has to be made the basis for a national consciousness, it needs a thorough reform. To begin that reform, it has to be realized that it is the violent and tribal-patriarchal nature of Pashtunwali which define the oppression of women and compound the particular economic oppression that women have to face in a larger patriarchal society. This continuation of tribal masculine code of honour and culture strip women of their human agency and make them property and objects of men’s desire and subservient to men’s ideas of arranging the private, public and social spaces.

This is true for all patriarchy, but the particular form of patriarchy embedded in Pashtun society and cultural code, which is based on proving masculinity through violence and preserving ‘honour’ through total objectification of women, is particularly dehumanizing. Reforming this cultural code has to begin from defining a new Pashtun masculinity.

The rhetorical question is often invoked, “Sanga Pukhtun ye marra” (Which kind of Pashtun are you?), which may refer to standing by your word but ultimately falls back on the trope of masculinity defined violently and vis-à-vis women. If it is not questioned and challenged, the political, epistemological, domestic and intimate violence that Pashtun women face will continue as an ontological reality. This cultural nationalism – where cultural identity is taken as the root and essential truth – not only displaces cultural imagination from the historical moment but also perpetuates different forms of violence which go into making of any identity.

The second position, though not as insidious as the first one, still believes in perpetuation of the fate of women till a ‘promised’ time. The misunderstanding, as pointed out earlier, is that of both the national and the woman/gender question. First of all, there is no sharp ‘resolution’ to the Pashtun question in the context of Pakistan, in any case. By that I mean that the national question in Pakistan is not about the possibility of an autonomous or independent nation-state but revolves around questions of civil and human rights. The guarantee for the resolution of the national question in the context of Pakistan will be the de jure rule and application of the constitution as well as the implementation of policies which neutralize or equalize the systems and structures of discrimination and exploitation which exploit the periphery to benefit and develop the core of the country. This, of-course, cannot be done without a larger movement against Pakistan’s particular capitalist mode of economy. So, believing that somehow the ‘national’ question, i.e. the exploitation of the periphery and the people in there would be solved without challenging the logic of capitalist economy and development is not only naïve but reverts to cultural nationalism in the final analysis.

The misunderstanding about the woman/gender question in relation to the national question is that women are seen outside the scope of the latter. And so, the struggle of women against patriarchy is assigned to an intimate sphere, separated from the rhythms of national development and exploitation. There is a vulgar assumption which blames policies of the state and political exploitation for the oppression of women in Pashtun society but there is only a grain of truth in that. Patriarchy was there long before the current political exploitation came into being. The current political system, through its logic of economic production, has changed the form of the patriarchal oppression and exploitation, but it doesn’t mean that patriarchy in Pashtun society is totally determined by the political structure and policies. There is a degree of cultural and social autonomy to the patriarchal oppression and that needs to be articulated in the national question as a struggle that sees women as part of that nation.

The struggle against political oppression and patriarchy is an integral one. Both go hand in hand. If the aim of political struggle (against oppression by the state as it exists) is a national consciousness, then erasing the struggle of women and ignoring the evils of patriarchy at best will give a truncated and half ‘national’ consciousness. The political oppression that Pashtuns face is integrally linked to relations of difference (gender, caste). And all these relations of difference are integrally related to the category and process of class. There are no autonomous and independent systems of oppression. Patriarchy and the national oppression don’t simply coincide at particular moments to result in an aggregated structure and thus feeling of oppression to women. Both the national oppression and patriarchy are linked (and integrated with other structures of oppression such as class and caste). Solving the national question without solving the gender/woman question is, thus, only daydreaming.

One basic thing about the oppression that Pashtuns face which has to be understood: that it is not an end in itself but is, in fact, a means to an end. Simply put, they are discriminated against by the state not because we are Pashtun and Pakistan by default has to hate them – but it is because in oppressing and discriminating them, the state gets some benefits. This nuance is important to understand if we have to escape reactionary forms of nationalism and instead want to articulate a progressive nationalist politics. The structural racism, discrimination and oppression that we face is part of the power structure of the state and we can’t see and tackle our reality in isolation from other relations and the overall structure of power.

In Pakistan, there are some avenues opened for upward social mobility of Pashtuns. In fact, Pashtuns as a whole have been integrated into economy of the country but simultaneously they are oppressed for strategic gains of the state. We have to see where the immediate oppression based on our national (ethnic) identity fits in the larger system of power. We can’t isolate the system or set of structural attitudes that dehumanize and oppresses Pashtuns from those systems which oppress others on the basis of class, gender, ethnic identities, sect and caste. These all are interrelated.

The oppression that a Pashtun face in Pakistan is because of the same system which oppresses any Pakistani woman, a Baloch, a Punjabi labourer, a Hazara Shia, a Sindhi missing person, etc. These are integral relations of oppression and thus power. If we go on repeating the mantra that the national identity of being Pashtuns is essential to the oppression that Pashtuns face, we will be going down a reactionary rabbit hole. But if we understand that the oppression that Pashtuns face is interrelated and integral to that which others face, then the very ‘nationalist’ politics becomes a ground for progressive politics and opens up the possibilities of a wider politics on the basis of solidarity.

(to be continued)

Imagining a Pashtun culture and nation, therefore, is not possible without rooting it in the particular role, place and status of women.

If Pashtunwali has to be made the basis for a national consciousness, it needs a thorough reform

This is not to say that there is something inherently wrong in being a Pashtun or in Pashtun culture. Asserting that will be to essentialize a culture and a people - and thus will be reducing them to be nothing more than automatons whose behavior is determined by social structures which are timeless, and from the grip of which it is impossible to escape. All these particular social structures, attitudes and behaviors are the result of a historical and political conjuncture, and they can’t be understood without situating them in the historicity of the moment. Thus, they are neither eternal nor essential to a people. The identification of a people with rigid and dehumanizing social structures and attitudes is an epistemological violence which traps people in the ironclad prison of discourse and abstract the historical socio-political circumstances from determining the social form.

There have been two kinds of positions regrading this ossification of culture. The first one, as pointed out earlier, is a kind of essentialized celebration of culture which has been internalized by many Pashtuns and a significant part of Pashtun political consciousness and imagination. This one justifies the place of women, as we see it, through invoking Pakhtunwali or Pashtunwali, which is a medieval tribal code for social order and function of the Pashtun society. The other one accepts that there exists a particular oppression of women in Pashtun society but then their solution goes through the rabbit hole of prioritization, hierarchy and thus compartmentalization of struggle. The argument can be summarized as saying that “first we should solve the ‘national’ question and then after that we will solve the ‘woman’ question.” That argument is wrong on two counts, as it misunderstands both the national and the woman questions. By national question we mean here the resolution of the oppression which Pashtuns as the periphery face and how they as a whole people are produced as the ‘Other’ in the national imagination of Pakistan. The woman question may refer to a lot of things, but most important among them is the patriarchal structure of our domestic and public spaces, the participation of women in public spaces, equality of all genders in terms of opportunities and participation and of social acceptance that women can make their own choices and have full agency. That argument essentially also leads to fragmentation of struggles. The truth, both in theory and in praxis, lies between these two ossified positions, i.e. somewhere between stating that Pashtunwali has to be honoured and that the woman question can wait till the national question is solved.

I argue against both of these positions and towards an integrated conceptualization of the national and gender struggle which can lead to a broader articulation of integral struggles.

The argument from Pashtunwali is ahistorical as well as an ossification of imagination in a time past, thus disregarding the determinations and necessities of the social and political structures of the moment. Pashtunwali, in this age, is an archaic tribal code. In any case, Pashtunwali is an unwritten code which has many variants across the Pashtun lands and in some ways guides the social and cultural arrangements in Pashtun society. Though it does have its egalitarian precepts, many of its lived tenets make it an oppressive and misogynistic system. While every tribal society has its moral and legal tribal codes and they are developed in response to specific historical socio-political settings (and in turn may also define the socio-political settings), in case of Pashtunwali the problem arises when it is seen as an ideal or as a substrate for a political national consciousness. The aspects of Pashtunwali like Melmastia (hospitality), Hujra, Patt (honour in standing to the oppressor), Nanawatay (solving of disputes through intervention of elders or admitting your fault) are all egalitarian values and make Pashtunwali a code which ensured a social order and cohesion at certain times.

Having said that, the aspects of Pashtunwali which are not just incompatible with the precepts of human dignity but are downright oppressive. These would be the patriarchal and misogynist rooting of the meaning of social order and individual honour. Valwar (something like Vani), Ghag (announcing that you are going to marry that woman and thus no one else should try to be a suitor for her), Turr (allegation of impropriety on women), Purdah (a forced one at that) and violent conception of honour which is inseparably tied to the bodies and choices of women make Pashtunwali the de facto oppressive system for women in Pashtun society. The institutions of Jirga and Hujra which are touted as the evidence for social harmony of Pashtun society are all male-dominated spaces and work to exclude and erase women. They exclude women not only from leadership, but operate in ways that erase their very existence in public spaces. Pashtunwali is a tribal code which was born in an age of violence and thus it celebrates the violent masculine aspects in lived social reality rather than emphasizing the egalitarian social values.

The misogynist and patriarchal nature of the problem of application of Pashtunwali is compounded by the undue and uncritical celebration of it by some in nationalist quarters.

If Pashtunwali has to be made the basis for a national consciousness, it needs a thorough reform. To begin that reform, it has to be realized that it is the violent and tribal-patriarchal nature of Pashtunwali which define the oppression of women and compound the particular economic oppression that women have to face in a larger patriarchal society. This continuation of tribal masculine code of honour and culture strip women of their human agency and make them property and objects of men’s desire and subservient to men’s ideas of arranging the private, public and social spaces.

This is true for all patriarchy, but the particular form of patriarchy embedded in Pashtun society and cultural code, which is based on proving masculinity through violence and preserving ‘honour’ through total objectification of women, is particularly dehumanizing. Reforming this cultural code has to begin from defining a new Pashtun masculinity.

The rhetorical question is often invoked, “Sanga Pukhtun ye marra” (Which kind of Pashtun are you?), which may refer to standing by your word but ultimately falls back on the trope of masculinity defined violently and vis-à-vis women. If it is not questioned and challenged, the political, epistemological, domestic and intimate violence that Pashtun women face will continue as an ontological reality. This cultural nationalism – where cultural identity is taken as the root and essential truth – not only displaces cultural imagination from the historical moment but also perpetuates different forms of violence which go into making of any identity.

The second position, though not as insidious as the first one, still believes in perpetuation of the fate of women till a ‘promised’ time. The misunderstanding, as pointed out earlier, is that of both the national and the woman/gender question. First of all, there is no sharp ‘resolution’ to the Pashtun question in the context of Pakistan, in any case. By that I mean that the national question in Pakistan is not about the possibility of an autonomous or independent nation-state but revolves around questions of civil and human rights. The guarantee for the resolution of the national question in the context of Pakistan will be the de jure rule and application of the constitution as well as the implementation of policies which neutralize or equalize the systems and structures of discrimination and exploitation which exploit the periphery to benefit and develop the core of the country. This, of-course, cannot be done without a larger movement against Pakistan’s particular capitalist mode of economy. So, believing that somehow the ‘national’ question, i.e. the exploitation of the periphery and the people in there would be solved without challenging the logic of capitalist economy and development is not only naïve but reverts to cultural nationalism in the final analysis.

The misunderstanding about the woman/gender question in relation to the national question is that women are seen outside the scope of the latter. And so, the struggle of women against patriarchy is assigned to an intimate sphere, separated from the rhythms of national development and exploitation. There is a vulgar assumption which blames policies of the state and political exploitation for the oppression of women in Pashtun society but there is only a grain of truth in that. Patriarchy was there long before the current political exploitation came into being. The current political system, through its logic of economic production, has changed the form of the patriarchal oppression and exploitation, but it doesn’t mean that patriarchy in Pashtun society is totally determined by the political structure and policies. There is a degree of cultural and social autonomy to the patriarchal oppression and that needs to be articulated in the national question as a struggle that sees women as part of that nation.

The struggle against political oppression and patriarchy is an integral one. Both go hand in hand. If the aim of political struggle (against oppression by the state as it exists) is a national consciousness, then erasing the struggle of women and ignoring the evils of patriarchy at best will give a truncated and half ‘national’ consciousness. The political oppression that Pashtuns face is integrally linked to relations of difference (gender, caste). And all these relations of difference are integrally related to the category and process of class. There are no autonomous and independent systems of oppression. Patriarchy and the national oppression don’t simply coincide at particular moments to result in an aggregated structure and thus feeling of oppression to women. Both the national oppression and patriarchy are linked (and integrated with other structures of oppression such as class and caste). Solving the national question without solving the gender/woman question is, thus, only daydreaming.

One basic thing about the oppression that Pashtuns face which has to be understood: that it is not an end in itself but is, in fact, a means to an end. Simply put, they are discriminated against by the state not because we are Pashtun and Pakistan by default has to hate them – but it is because in oppressing and discriminating them, the state gets some benefits. This nuance is important to understand if we have to escape reactionary forms of nationalism and instead want to articulate a progressive nationalist politics. The structural racism, discrimination and oppression that we face is part of the power structure of the state and we can’t see and tackle our reality in isolation from other relations and the overall structure of power.

In Pakistan, there are some avenues opened for upward social mobility of Pashtuns. In fact, Pashtuns as a whole have been integrated into economy of the country but simultaneously they are oppressed for strategic gains of the state. We have to see where the immediate oppression based on our national (ethnic) identity fits in the larger system of power. We can’t isolate the system or set of structural attitudes that dehumanize and oppresses Pashtuns from those systems which oppress others on the basis of class, gender, ethnic identities, sect and caste. These all are interrelated.

The oppression that a Pashtun face in Pakistan is because of the same system which oppresses any Pakistani woman, a Baloch, a Punjabi labourer, a Hazara Shia, a Sindhi missing person, etc. These are integral relations of oppression and thus power. If we go on repeating the mantra that the national identity of being Pashtuns is essential to the oppression that Pashtuns face, we will be going down a reactionary rabbit hole. But if we understand that the oppression that Pashtuns face is interrelated and integral to that which others face, then the very ‘nationalist’ politics becomes a ground for progressive politics and opens up the possibilities of a wider politics on the basis of solidarity.

(to be continued)