“The forests are thick and shady, the fruits and flowers abundant” wrote Xuanzang, the Chinese pilgrim, who visited Swat in 629 CE, quoted by Sultan-i-Rome in his recently published book, ‘Land and forest governance in Swat; transition from tribal system to State to Pakistan’ published by Oxford University Press.

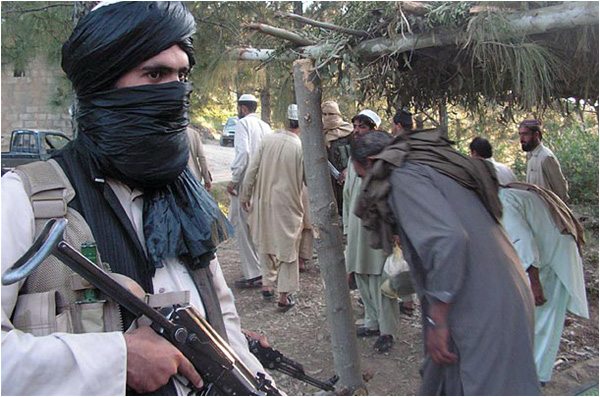

“The forests are thick and shady, the fruits and flowers abundant” wrote Xuanzang, the Chinese pilgrim, who visited Swat in 629 CE, quoted by Sultan-i-Rome in his recently published book, ‘Land and forest governance in Swat; transition from tribal system to State to Pakistan’ published by Oxford University Press.Unfortunately Swat has lately been known for the Taliban insurgency. Swat is, however, home to both ethnic and cultural diversity. It is one of the most cherished tourist destinations in Pakistan. In summer thousands of domestic tourists visit the valley. Prior to the September 2001 attacks on the World Trade Centre in the USA, foreigners also visited it in large numbers. Because of its rich Buddhist heritage, Swat used to be visited by Buddhist pilgrims from the world, especially from the South East and Far East Asian regions.

Mali's wesh system was actually a re-allotment or rotation of land among different clans

Along with the ancient heritage Swat is also famous for its natural beauty and weather. This is because of the forests here, especially in the upper highlands, surrounded by high hills. This terrain is known as Swat-Kohistan: the ethnically non-Pakhtun valleys of Bahrain and Kalam.

Because of the Taliban takeover and insurgency in 2007-09, the Swat valley became a flashpoint. Pakistani and foreign commentators wrote about the reasons behind the Taliban insurgency in Swat. Many assert that as the people of Swat were accustomed to the effective system of sharia in Swat during the Swat State era - from 1915, when the Swat State was established till 1969, when Swat State was merged with Pakistan - therefore, they rose against the contemporary governance of neglect, inefficiency and corruption.

Many other writers, who look at the Swat insurgency in isolation from what has been going on in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, see the insurgency in Swat as a class-war between the landowners and landless: the haves and haves-not.

Rome’s book ‘Land and forest governance in Swat; transition from tribal system to State to Pakistan’, though primarily written on forest and land management in Swat, Dir, Shangla, Indus Kohistan and Buner also helps us understand the land and ‘Sharia’ dimension to the recent upheaval there.

The first chapter of the book is a summary of the political history of Swat from the Buddhist period to date. It is the setting of the book.

The second chapter, on the land dimension, details how land and forests were distributed in the valley after the Yousafzai occupation of the valley in sixteenth century. The next chapters focus on forest conservation during the Swat State and after it till 2014.

Mahmood of Ghazni invaded Swat in the early eleventh century but it seems, as elsewhere in India during his expeditions, he abandoned it before the Yousafzai Pakhtuns captured it in the sixteenth century.

With the occupation of Swat the big challenge that arose was how to distribute the spoils of war, especially the fertile land, among the various clans and families within the Yousafzai Pakhtuns.

To meet the challenge an expert known as Shaikh Mali devised his ‘daftar’ (revenue record) and designed the famous wesh system for land distribution. Mali’s ‘daftar’ was so well-known in Swat then that when the famous Pashto poet and tribal leader Khushal Khan Khattak visited Swat in late seventeenth century he was astonished to note the popularity of Mali’s ‘Daftar’ and Akhund Darveza’s Makhzan. Khushal Khattak wrote that in Swat the people heeded to only the ‘Daftar’ and ‘Makhzan’.

Wesh is a Pashto word literarily means ‘distribution free of cost’. But Mali’s wesh system was actually a re-allotment or rotation of land among the different clans and families. It was not a permanent settlement. Under this rule the land was not given to any family or clan permanently but allotted for a fixed term of five, ten, fifteen or twenty years. The family would till the land till its tenure came to an end. Then the said portion of land was allotted to another family and the previous family was given some other piece.

Khushal Khan Khattak states that the natural beauty of Swat has been ruined since the Yousafzai occupation

This temporary settlement was an endeavour to avoid conflicts among the Yousafzai Pathans. But it inflicted serious harm on the land and forest management; and on the general development of the area too. The wesh system actually kept the people nomadic so they did not bother about constructing houses of good standing or planting orchards. Khushal Khan Khattak states in his poetic travelogue Swat Nama that the natural beauty of Swat is adequate to the taste of kings but it has been turned to ruins since the occupation by the Yousafzais. He further states that houses of the Swat Yousafzais are dirty and stinking while one can see large houses in good repair wherein live pretty girls of the ‘Kafirs’. (In seventeenth century there were still the dwellings of the Siaposh ‘Kafirs’, the ancestors of the Daradas of Swat and Dir).

Many writers on Swat have noted the impact of the wesh system. Rome quoted A.H McMahon and A.D. G. Ramsay, “One sees the evil results of the system (wesh system) everywhere - no orchards, no gardens, few, if any, trees except in the sacred precincts of a ziarat (shrine); even the masjids (mosques) are a mere roof of mud or thatching, whichever comes cheaper, resting on three sides on a rough mud or stone wall, which also encloses the courtyard or ghole on fourth side. Lands that have been irrigated from the beginning long before Pathan days, by water channels from the rivers and streams remain thus irrigated. All other lands depend upon rain for their crops, although large tracts could easily be brought under irrigation but little united labour”. And in 1926, Aurel Stein wrote “But the total absence of gardens and fruit-trees in this fertile and well-watered valley was striking. It was a sad illustration, seen also elsewhere in Swat, of the effects of the surviving Pathan custom wesh.”

The wesh system was romanticised as communism by celebrated authors like Sibte Hasan as well. Rome writes that Sibte Hasan saw it as the redistribution of land among the members of the tribe equally and hence has tried to justify holding of the land as the common property of the masses under the control of the state, as in communism. He, Rome, asserts that this was not the case although under the wesh system the dawtar -Shaikh Mali’s term daftar later became dawtar - was liable to frequent re-allotment, it has never been re-allotted equally among all the members of the tribe/clan/family for whatever the duration of the tenure was in the particular area. In fact every shareholder received only the share he possessed prior to the new wesh i.e. re-allotment or interchange.

The wesh system in Swat was like Hardin’s tragedy of commons where the common is the natural resource shared by many people without any regulation and each individual had the tendency to exploit the ‘common’ - land and forests - to his own advantage without any limit and concern for conservation; and eventually the ‘common’ was depleted and ruined.

‘Dawtar’ became so embedded into Pakhtun social code and identity that selling of it deprived the seller of his Pakhtun identity. Rome writes, “A person was recognised and entitled to be called Pakhtun as long as he retained his dawtar. By losing his dawtar for whatever reason ‘he and his offspring not only lost their identity as Pakhtuns and the membership of the tribe after a generation or two, but also their voice in their jargahs [village councils].” This founded the concept of stratification between Faqirs (people without the right of dawtar) and Pakhtuns.

Under the wesh system the Islamic right of women to own and inherit land was, as a rule, commonly not recognised. This was ascertained by Khushal Khtak Khattak in his visit to Swat in a verse: Da Baba da maal yawazey miras Khor di, na pa tarur di, na pa more di, na pa khor di [The menfolk keep everything to themselves what they inherit. No due share is ever granted to the womenfolk be that aunt or mother or sister]. This traditional practice remained the law of inheritance during the Swat State as well.

Along with the dawtar there was the tradition to give land to the religious leaders for their religious service and to the Khan - village chief - for hosting guests at his hujrah (guest rooms). This right was called serai. This was given permanently. Very often under the serai right the religious leaders and Khan got large chunks of land. Later during the Swat State era large swaths of lands were also allotted to people for political reasons. This produced a feudal system in the valley. This inherited disparity escalated the Taliban insurgency in Swat but cannot be called the single cause of the uprising given the geo-strategic dimension of the whole phenomenon.

Before the Swat state, there had been no written form of the rights’ holders/dawtaris. It was based on riwaj or tradition, and that was passed from generation to generation through word of mouth. The forests were not communal and were only owned by the concerned dawtar landowners and also by the serai land owners.

In addition to the purposes of construction the forest timber was (and is) used for burial purposes such as making wooden coffins; and for fencing the grave above the ground. Timber was also used in mosques and hujrahs especially in winter for heating purposes.

Felling of deodar trees for commercial purposes, especially from the Torwali and Kalam tracts, began in about 1850. This was mostly done by the Kaka Khel Mians of Ziarat Kaka Sahib in the district of Nowshera because of their relations both with the colonial government and with the Akhund of Swat, Abdul Ghafur alias Saidu Baba. Back then, most felling of trees was done in places near the river.

During the reign of Bacha Sahib, Mian Gul Abdul Wadud, the Kaka Khel Mians were favoured by the ruler because of their being the heirs of Kaka Sahib, a religious figure. Mian Rahim Shah Kakakhel, one of the timber contractors, was also in good books of the colonialists because of the former’s support in the Chitral expedition in 1895.

In the book Mr. Rome has also dispelled a number of myths expounded by writers and the general public. He states with reference that, “Prior to the establishment of the state there was no system of the management of forests and haphazard fallings were carried out.” This negates the sweeping statement of Inam-ur-Rahim and Alain Viaro in their book ‘Swat: an Afghan society in Pakistan’ which states, “The common resources including forest and brush-lands were communally utilised in a sustainable manner till the Swat State merger and different social groups had a well-regulated uniform and equitable access to these resources.”

Similarly Akbar S. Ahmad’s statement, “During his [Bacha Sahib’s] rule womenfolk were restored to their rightful place in society, and were given the rights and privileges expounded in the Shariat” is refuted by the author, quoting the Dir-Swat Land Disputes Enquiry Commission’s report of 1972 that the rule of inheritance in Swat State was riwaj, according to which females were not entitled to inherit property; and that the Bacha Sahib himself told the commission both orally and in writing that the rule of inheritance in Swat State ‘was Riwaj and not Shariat’. Not only this but the women were barred from selling what property they would get in Mahar on marriage.

The dawtar and land was owned only by the male members of the family. Neither Bacha Sahib nor his son, the Wali, made any law repugnant to this riwaj. Females were not given their inheritance right to land as prescribed by Sharia.

The Kalam tract comprising the scenic town of Kalam, valleys of Ushu and Utror, was never been a part of the Swat State except for the seven disputed years when the Swat State ruler annexed it on August 15, 1947 - when India was partitioned. Prior to that Kalam was a Tribal agency ruled by the British through the political agent of Swat, Dir and Chitral based in Malakand. This status of Kalam as an agency was because of the claims to it by the then three princely states - Swat, Dir and Chitral. However, due to ease of access by road, the rulers of Swat had an advantage to exploit its forests through their favourites - of the likes of the Kaka Khel Mians and the State’s wazirs (ministers and advisors).

When the ruler of the Swat State annexed Kalam in 1947 it still remained a disputed territory between the Pakistani government and State of Swat. In 1954 an agreement was reached between the Pakistani government and Wali of Swat that restored Kalam as a tribal agency with Pakistan and the Wali was appointed as its administrator only. Kalam was made a part of the Swat district in 1969 with the merger of the Swat State into Pakistan.

A few questions left unanswered by Rome in his book are worth mentioning here. What system was in practice regarding the land tenure in Swat before the Yousafzai occupation? We do not know anything about it. Or the question: what were the various ethnic groups living in Swat before or during the Yousafzai occupation? The reason perhaps is that the book is on forest and land management; and is not on anthropology or history of Swat.

Rome justly analysed the landholding system in Swat-Kohistan, writing that here the dawtar rests with three or four main tribes of the Torwali and Gawri people. He states that there was no wesh system here and the dawtar was thus in practice since ancient times. In the rest of Swat we see the dawtar derived from the wesh system. The people of Swat-Kohistan also call their land and forest holding rights as dawtar. Similarly in the Torwali tract of Swat-Kohistan we find dawtar system on the western (road) side of the Swat river whereas on the eastern side mostly one finds the logey -literarily smoke, meaning the forest ownership right - which is equally distributed among the dwellers based on their households. Why are there in existence two systems in a valley of people of the same ethnicity, living on two opposite sides of the Swat river? These are the questions Rome says need further research.

The book has about 600 pages full of citations and references. It has eight chapters and each chapter has a long list of notes and references at the end. The author has taken much time and pains in writing the book. It has a long bibliography - English, Urdu and Pashto books along with official reports, magazines, journals and official notifications.

Rome’s book is indeed a scholarly work added to the tapestry of research on the Swat valley in Pakistan.

Zubair Torwali is Executive Director at the Idara Baraye Taleem-o-Taraqi (IBT) and a freelance journalist based in Bahrain, Swat