Robert Malthus would have loved to be alive in Pakistan today. The discredited 19th Century English political economist and population alarmist was of course, the original purveyor of such tripe as, “the perpetual tendency of the race of man to increase (in numbers), beyond the means of subsistence is one of the general laws… which we can have no reason to expect to change.” And he would have been proud of the way we’ve been talking about our recent census.

He would hear echoes of his theories in the general despair. He would likely note, with glee, commentators extrapolating growth rates into infinity, speaking of a future of skyrocketing poverty, with “hordes of beggars roaming the streets”, warning of the nightmare of feeding and educating so many souls.

There is little doubt that since the last census, in 1998, more people have been added to Pakistan than anyone had expected. This is why there are good reasons to redouble efforts to provide every household with the resources it needs to make optimal family size choices. There are also good reasons to begin focusing on the mispricing of shared resources, such as water, to guard against future shortages. But it is also important to note that there is a hidden success story within our population boom. Without knowing it is there, however, we hurt our odds of replicating it, or, indeed, improving on it.

So the story we will not repeat is this: almost every class and group of people showed a stunning increase in numbers between 1998 and 2017. The story we need to talk about is that there is one important group whose ranks actually fell over this period—those of the desperately poor.

Not only did the percentage of Pakistanis below the poverty line fall over the last few decades, it fell so fast, that despite the census recording the addition of 75 million people, there are actually at least 25 million fewer people below the line than in 1998. (The poverty line was last marked at around 3,000 rupees per person, so Rs15,000 for a family of five). In what the World Bank has recently referred to as a “staggering” and “remarkable” success, the “headcount ratio” or the percentage of people below the national poverty line declined from nearly 65% at the turn of this century to just under 30% in 2014. Three years of economic growth since then have almost certainly reduced this percentage further.

Measured against the standard international poverty line (which, in each country is the local equivalent purchasing power of $1.90 per day), the percentage of people below the line stands at just over 6% which is dramatically lower than that of regional peers such as India (21%) and Bangladesh (18%).

So can we believe the numbers? If so, what can we learn from this rapid poverty reduction experience?

Trusting the numbers

The numbers aren’t cooked up. They are the result of extensive studies and analysis, utilizing large-scale household surveys over years, recently validated by the World Bank, which has provided technical assistance along the way. The numbers are “consumption-based”, so they include the money families receive from all sources. The standards for what constitutes desperate poverty are robust, and are actually set far higher than both the international standard, and Pakistan’s own earlier poverty threshold. The headcount ratio for earlier years, based on the new poverty line, is constructed by using credible inflation data.

No measure or measurement of poverty is perfect. It also needs to be noted that a large percentage of people who are above the poverty line, are still considered to be vulnerable as even a small shock could push them back. Nonetheless, there is no serious doubt about the direction and magnitude of the headcount ratio drop. Data about growth in pukka housing, toilet use, motorcycle ownership and school enrollment all corroborate this story.

How and what now?

Our poverty levels have fallen because of economic growth, soaring remittances, a charitable population, and government subsidies and transfers.

It has been fashionable for years in Pakistan to criticize growth in the country as pro-rich. This bashing appears to be based more on anti-capitalist biases than reality. Because the reality is that (as per the World Bank’s 2014 report on poverty in Pakistan), as much as a third of the reduction in Pakistani poverty this century can be ascribed to increases in non-farm wages. Simply put, economic growth has led to more jobs outside of farms e.g. in cities. This, and the ability of skilled workers to migrate abroad, has increased the competition for labour, driving up real wages. Government minimum wage rules have likely also played an important role, more so in some provinces than others. To get a sense of relatively strong wages, it is worth knowing that the average Pakistani textile worker earns more than twice the average textile worker in Bangladesh.

There should be no debate about the fact that economic growth in developing countries almost always benefits the poor. Every major study has found this, and all serious economists agree on this. The magnitude of impact of course, varies, and Pakistan’s recent growth experience has generally been shown to have had a higher than average impact on poverty reduction.

In short, the faster we grow, the quicker we will reduce poverty. Period. The good news here is that despite a vocal anti-capitalist contingent, market-led economic growth has been, and remains a government priority across the political spectrum. It must remain so. Protections for labour, primarily minimum wage and working condition rules, must also continually be strengthened.

The next driver, remittances, is a bit more troubling, as structural changes, and sluggish growth prospects in destination countries, point towards slower growth, if not outright reduction. Between 1998 and 2017, remittances to Pakistan went from just over a billion dollars to nearly twenty billion dollars a year. Even accounting for the fact that some of the increase in remittances is just a reflection of more people using official channels, the increase, to over 7% of our total national income, is stunning. While the majority of remittance income is received by people who are comfortably over the poverty line, enough of it goes to poor households to make a dent in poverty, and there is a wealth of economic literature exploring and quantifying this. In addition, of course, as alluded to earlier, the ability of skilled and semi-skilled labour to find employment overseas, has contributed to higher home country wages as local businesses compete for talent.

In addition to changes in the global economy, the outlook for remittances is also bleak at least partly as a result of its own success. As the wages of Pakistanis grow beyond those of Bangladeshis and Indians, they become less competitive as migrant labour.

So, continued poverty reduction will have to rely more on domestic resources, the pool of which will grow, as our economy continues to grow.

Direct transfers from friends and family, and charitable contributions such as Zakat, are one such domestic resource, and their impact on consumption in poor households has been extensively documented. As such, they are widely credited as an important poverty-reduction driver. These should and will likely continue. But as the economy grows, and family sizes fall, the most important poverty reduction tool will be direct transfers from the government. Such transfers can also help address the regional imbalances in poverty that are not being addressed by informal transfers, particularly in Balochistan.

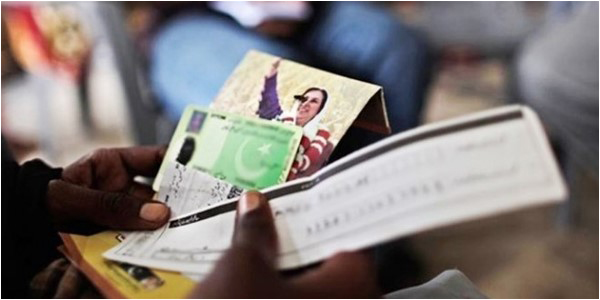

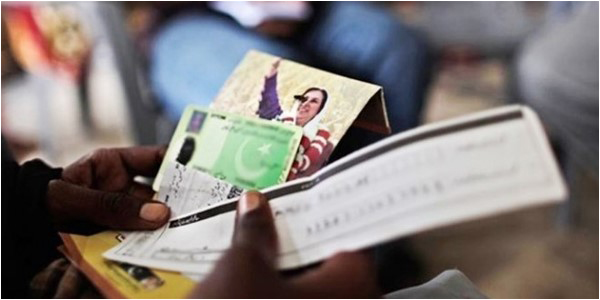

The largest program of such transfers is the Benazir Income Support Program (BISP). At present, the crux of this program is the distribution of around a billion dollars a year to poor households who receive a cash transfer of just over 1,500 rupees a month. The World Bank’s June 2014 report calculated that the program was responsible for a 2.2% reduction in the “poverty headcount”.

Why so low? Not because it is poorly designed. In fact the academic consensus is that it is very well designed, and effectively targets poor households. The reason it falls short is because it is just not enough. The transfers are too small, and too few people receive them. Many criticisms of the program (e.g. recipients are prioritized on the basis of political affiliations) would melt away if there was enough money to go around.

The weight of the evidence suggests that BISP works. If it works and it isn’t big enough, then the answer is that it needs to be many multiples of its current size. It’s as simple as that. It is possible to afford this by slashing untargeted subsidies found throughout our economy. Prime candidates are subsidies to consumers for power, and natural gas, to agricultural producers, and to favoured industries. All of these have been shown to deliver benefits disproportionately to the non-poor.

In dramatically expanding BISPs scope, policymakers must engage local economists and researchers to assist in policy design (the Centre for Economic Research in Pakistan, comes to mind). There is a wealth of experience with cash transfers in developing countries that can be drawn upon to ensure that the poor benefit as much as possible, and positive impact across the economy is maximized.

The upshot of it all is this: There are a lot of people in Pakistan, and there will be a lot more. We have done a relatively good job ensuring that fewer and fewer people experience complete economic deprivation. Nonetheless, at least 50 million people are still desperately poor. That we make bringing them out of the poverty trap our number one priority is not only a moral imperative, it also makes economic sense. We will see spillover effects in terms of better health outcomes, higher school enrollment, and a more stable and just society. We know we can do this, because we have reduced poverty on this magnitude before. Of the factors that helped reduce poverty for us in the past two decades, the ones that will be the most critical for the next two decades will be economic growth, and a massive expansion in targeted programs such as the BISP.

The ideas put forth by Robert Malthus have been put to rest in much of the world. Let us, by our actions, make sure they do not arise from their slumber.

The writer is a Lahore based columnist and consultant. He has previously served as a Director at a major European investment bank. He was also, briefly, a management consultant at a leading global consulting firm, where he participated in an extensive social sector initiative led by the Government of the Punjab. The views expressed are entirely his own. He tweets @assadahmad

He would hear echoes of his theories in the general despair. He would likely note, with glee, commentators extrapolating growth rates into infinity, speaking of a future of skyrocketing poverty, with “hordes of beggars roaming the streets”, warning of the nightmare of feeding and educating so many souls.

Not only did the percentage of Pakistanis below the poverty line fall over the last few decades, it fell so fast, that despite the census recording the addition of 75 million people, there are actually at least 25 million less people below the line than in 1998

There is little doubt that since the last census, in 1998, more people have been added to Pakistan than anyone had expected. This is why there are good reasons to redouble efforts to provide every household with the resources it needs to make optimal family size choices. There are also good reasons to begin focusing on the mispricing of shared resources, such as water, to guard against future shortages. But it is also important to note that there is a hidden success story within our population boom. Without knowing it is there, however, we hurt our odds of replicating it, or, indeed, improving on it.

So the story we will not repeat is this: almost every class and group of people showed a stunning increase in numbers between 1998 and 2017. The story we need to talk about is that there is one important group whose ranks actually fell over this period—those of the desperately poor.

Not only did the percentage of Pakistanis below the poverty line fall over the last few decades, it fell so fast, that despite the census recording the addition of 75 million people, there are actually at least 25 million fewer people below the line than in 1998. (The poverty line was last marked at around 3,000 rupees per person, so Rs15,000 for a family of five). In what the World Bank has recently referred to as a “staggering” and “remarkable” success, the “headcount ratio” or the percentage of people below the national poverty line declined from nearly 65% at the turn of this century to just under 30% in 2014. Three years of economic growth since then have almost certainly reduced this percentage further.

Measured against the standard international poverty line (which, in each country is the local equivalent purchasing power of $1.90 per day), the percentage of people below the line stands at just over 6% which is dramatically lower than that of regional peers such as India (21%) and Bangladesh (18%).

So can we believe the numbers? If so, what can we learn from this rapid poverty reduction experience?

As much as a third of the reduction in Pakistani poverty this century can be ascribed to increases in non-farm wages. Simply put, economic growth has led to more jobs outside of farms e.g. in cities

Trusting the numbers

The numbers aren’t cooked up. They are the result of extensive studies and analysis, utilizing large-scale household surveys over years, recently validated by the World Bank, which has provided technical assistance along the way. The numbers are “consumption-based”, so they include the money families receive from all sources. The standards for what constitutes desperate poverty are robust, and are actually set far higher than both the international standard, and Pakistan’s own earlier poverty threshold. The headcount ratio for earlier years, based on the new poverty line, is constructed by using credible inflation data.

No measure or measurement of poverty is perfect. It also needs to be noted that a large percentage of people who are above the poverty line, are still considered to be vulnerable as even a small shock could push them back. Nonetheless, there is no serious doubt about the direction and magnitude of the headcount ratio drop. Data about growth in pukka housing, toilet use, motorcycle ownership and school enrollment all corroborate this story.

As the economy grows, and family sizes fall, the most important poverty reduction tool will be direct transfers from the government

How and what now?

Our poverty levels have fallen because of economic growth, soaring remittances, a charitable population, and government subsidies and transfers.

It has been fashionable for years in Pakistan to criticize growth in the country as pro-rich. This bashing appears to be based more on anti-capitalist biases than reality. Because the reality is that (as per the World Bank’s 2014 report on poverty in Pakistan), as much as a third of the reduction in Pakistani poverty this century can be ascribed to increases in non-farm wages. Simply put, economic growth has led to more jobs outside of farms e.g. in cities. This, and the ability of skilled workers to migrate abroad, has increased the competition for labour, driving up real wages. Government minimum wage rules have likely also played an important role, more so in some provinces than others. To get a sense of relatively strong wages, it is worth knowing that the average Pakistani textile worker earns more than twice the average textile worker in Bangladesh.

There should be no debate about the fact that economic growth in developing countries almost always benefits the poor. Every major study has found this, and all serious economists agree on this. The magnitude of impact of course, varies, and Pakistan’s recent growth experience has generally been shown to have had a higher than average impact on poverty reduction.

In short, the faster we grow, the quicker we will reduce poverty. Period. The good news here is that despite a vocal anti-capitalist contingent, market-led economic growth has been, and remains a government priority across the political spectrum. It must remain so. Protections for labour, primarily minimum wage and working condition rules, must also continually be strengthened.

The next driver, remittances, is a bit more troubling, as structural changes, and sluggish growth prospects in destination countries, point towards slower growth, if not outright reduction. Between 1998 and 2017, remittances to Pakistan went from just over a billion dollars to nearly twenty billion dollars a year. Even accounting for the fact that some of the increase in remittances is just a reflection of more people using official channels, the increase, to over 7% of our total national income, is stunning. While the majority of remittance income is received by people who are comfortably over the poverty line, enough of it goes to poor households to make a dent in poverty, and there is a wealth of economic literature exploring and quantifying this. In addition, of course, as alluded to earlier, the ability of skilled and semi-skilled labour to find employment overseas, has contributed to higher home country wages as local businesses compete for talent.

In addition to changes in the global economy, the outlook for remittances is also bleak at least partly as a result of its own success. As the wages of Pakistanis grow beyond those of Bangladeshis and Indians, they become less competitive as migrant labour.

So, continued poverty reduction will have to rely more on domestic resources, the pool of which will grow, as our economy continues to grow.

Direct transfers from friends and family, and charitable contributions such as Zakat, are one such domestic resource, and their impact on consumption in poor households has been extensively documented. As such, they are widely credited as an important poverty-reduction driver. These should and will likely continue. But as the economy grows, and family sizes fall, the most important poverty reduction tool will be direct transfers from the government. Such transfers can also help address the regional imbalances in poverty that are not being addressed by informal transfers, particularly in Balochistan.

The largest program of such transfers is the Benazir Income Support Program (BISP). At present, the crux of this program is the distribution of around a billion dollars a year to poor households who receive a cash transfer of just over 1,500 rupees a month. The World Bank’s June 2014 report calculated that the program was responsible for a 2.2% reduction in the “poverty headcount”.

Why so low? Not because it is poorly designed. In fact the academic consensus is that it is very well designed, and effectively targets poor households. The reason it falls short is because it is just not enough. The transfers are too small, and too few people receive them. Many criticisms of the program (e.g. recipients are prioritized on the basis of political affiliations) would melt away if there was enough money to go around.

The weight of the evidence suggests that BISP works. If it works and it isn’t big enough, then the answer is that it needs to be many multiples of its current size. It’s as simple as that. It is possible to afford this by slashing untargeted subsidies found throughout our economy. Prime candidates are subsidies to consumers for power, and natural gas, to agricultural producers, and to favoured industries. All of these have been shown to deliver benefits disproportionately to the non-poor.

In dramatically expanding BISPs scope, policymakers must engage local economists and researchers to assist in policy design (the Centre for Economic Research in Pakistan, comes to mind). There is a wealth of experience with cash transfers in developing countries that can be drawn upon to ensure that the poor benefit as much as possible, and positive impact across the economy is maximized.

The upshot of it all is this: There are a lot of people in Pakistan, and there will be a lot more. We have done a relatively good job ensuring that fewer and fewer people experience complete economic deprivation. Nonetheless, at least 50 million people are still desperately poor. That we make bringing them out of the poverty trap our number one priority is not only a moral imperative, it also makes economic sense. We will see spillover effects in terms of better health outcomes, higher school enrollment, and a more stable and just society. We know we can do this, because we have reduced poverty on this magnitude before. Of the factors that helped reduce poverty for us in the past two decades, the ones that will be the most critical for the next two decades will be economic growth, and a massive expansion in targeted programs such as the BISP.

The ideas put forth by Robert Malthus have been put to rest in much of the world. Let us, by our actions, make sure they do not arise from their slumber.

The writer is a Lahore based columnist and consultant. He has previously served as a Director at a major European investment bank. He was also, briefly, a management consultant at a leading global consulting firm, where he participated in an extensive social sector initiative led by the Government of the Punjab. The views expressed are entirely his own. He tweets @assadahmad