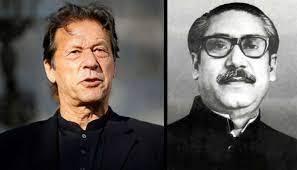

Pakistani political leaders have recently developed a penchant for comparing themselves with Sheikh Majeeb-ur-Rehman—the leader of Awami League, who led Bangladesh to Independence. Or more precisely they like to compare the crisis their political activism has generated to the one Pakistani state was facing in 1971, when Pakistan was dismembered into two parts. Nawaz Sharif did this when he was ousted from power and was leading a public mobilization campaign in July 2017 and now Imran Khan did it while he was leading a public protest campaign a little less than a month after his ouster from power. One thing is in fact common between Sheikh Mujeeb and the present-day leaders of Pakistani society—both Sheikh Mujeeb on the one hand and Imran Khan and Nawaz Sharif on the other, were victims of the military's high handedness or this was how they perceived their situation to be.

Sheikh Mujeeb and his people were undoubtedly the victims of the then military leaders’ evil designs and acts. Bengali people and their leader, Sheikh Mujeeb faced military brutalities and before that military machinations to deprive them of their democratic rights of representation in the elected bodies, government and state structures. Sheikh Mujeeb was the leader of Bengali Muslims—a ethnic community within the state of Pakistan which was a majority community as far as size of the population was concerned and yet they were deprived of their economic and political rights. Sheikh Mujeeb led his party Awami league (AL) to an electoral victory in 1971 parliamentary elections with AL securing all but two seats in East Pakistan and simply a majority in the national assembly of United Pakistan. And yet West Pakistan's Punjab dominated bureaucracy, military and political leaders refused to transfer power to Sheikh Mujeeb and his party in 1971, leading to gruesome events that led to disintegration of Pakistan.

1971 was the first general election in Pakistan’s history. We can say after independence this was the first time genuine politically representative institutions were being created through electoral exercise on a national scale. Since Pakistan came into being the state structure was dominated first by bureaucrats mostly belonging to migrant communities who migrated to West Pakistan from Muslim minority provinces of India, where Muslims were in minorities and which were now part of India. These migrant bureaucrats were later pushed out gradually and partially during the Ayub and Bhutto eras and Punjabi bureaucrats started to dominate the state structures in the absence of democratic institutions. Pashtun also made their way into state structures during Ayub’s period. So, till 1971, migrants from India’s minority provinces, Punjabis and Pashtuns dominated the state structures and in the absence of democratic institutions the policy making and the process of distribution of resources was completely in the hands of state machinery dominated by these three ethnic groups. After 1958 (some say after 1954) martial law started to dominate the process of policy making and distribution of resources and the military officer corps, throughout this period till 1971, was largely drawn from Punjabi and Pashtun ethnic groups. State financed industrialization, agriculture revolutions and employment opportunities offered by the state, all were coming to the areas of Pakistan, where these three communities dominated. This was the process through which Bengalis, Baloch, Sindhi and other ethnic communities were marginalized. Bengali were quick to respond in a violent manner—a process which culminated in the 1971 civil war.

Now let’s examine the claim of Nawaz Sharif and Imran Khan that they or their political activism should be compared to Sheikh Mujeeb’s political struggle or his situation. Nothing could be more preposterous than these claims made by Punjab-centric leaders like Imran Khan and Nawaz Sharif. Nawaz Sharif is totally dependent on the votes of Punjabi middle classes residing in the area between Jhelum and Sahiwal—if you move along Grand Trunk Road. Now we are witnessing a process through which these Punjabi middle classes were seemingly shifting loyalties towards Imran Khan. But Imran Khan is no less a Punjab-centric leader than Nawaz Sharif. Imran Khan also enjoys the loyalties of another ethnic group which dominates the bureaucracy, both civil and military—I mean the Pashtuns. To call Nawaz Sharif and Imran Khan darlings of the state would not be an exaggeration. Punjabi middle classes, which these two leaders represent, are also the darlings of the state.There are no centrifugal forces in Punjab. Pashtuns on the other hand ethnically display a patent form of cultural particularism. But nonetheless the centrifugal political thinking is not the dominant trend in Pashtun society in the present times. The bureaucracy and army generals display a particular form of favoritism towards leaders from their ethnic stocks. Nawaz Sharif and Imran Khan can launch abusive diatribes against the military and its top brass and yet they can get away with it. They can both intrude into the internal affairs of the military and yet remain safe from highhandedness of the military and its intelligence agencies. Both leaders are playing with the ignorance about their own history and short memory of Pakistani masses—Pakistanis don’t seem to remember why Eastern Pakistan was separated into an independent country? And Pakistan media never tells them that Punjab-centric parties and their politics will not change anything in the power structures of the country, no matter how revolutionary both Nawaz Sharif and Imran Khan may try to sound.

Marginalized communities like Balochis and to some extent Sindhis are not part of Nawaz Sharif and Imran Khan’s stories. One strong indicator of the Punjab-centric nature of Imran Khan and Nawaz Sharif’s politics is the fact that both carried out long marches between Lahore and Islamabad—an area that could be described as Punjab’s heartland. Whatever may be the outcome of their exhaustive and useless contest, one thing is for sure that the outcome of this contest will not introduce any change in the nature of the process of distribution of resources in the society. Its only Punjabi middle classes are changing loyalties from one Punjab-centric party to another one. Military, bureaucracy and Punjab’s leadership will continue to secure the lion’s share of resources in our society. Marginalized communities can lick their wounds while the Punjab elites reach a re-settlement agreement over the spoils.