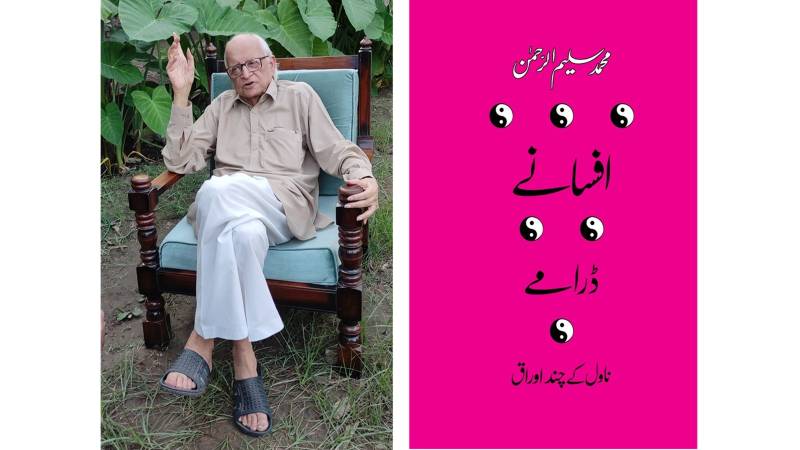

Reading Muhammad Saleem ur Rehman sahib can be like discovering an old leather-bound volume in some long-forgotten almirah in a locked storeroom no one goes to anymore. I say this because his recently published volume of writings contains a beautifully evocative lexicon that is rapidly being lost to our collective memory and usage. However, not just quaint vestiges of the past, his recently published collection of twelve stories, two dramas and some pages from an unfinished novel is also like the Borgesian Book of Ages that the brilliant American speculative fiction writer Ted Chiang talks about in his tale The Story of Your Life. The Book of Ages that contains every detail of the future so that if it is read our future is known and pre-determined. Such is Saleem sahib’s simultaneous and unique bond with antiquity and his nexus with modernity. This is what endows tremendous diversity to his writing and makes it extraordinary in its thematic range and imaginative reach. The volume of collected earlier published pieces with its delightfully shocking pink cover — youthful is the heart and mind that has envisioned these tales — is the precious output of a man whose gaze encompasses many an age.

Saleem sahib resides in Lahore, beyond the enclosed deep shadows of Shalimar Gardens, like a beneficent guardian spirit of the devotees of the written word. A Saeen for scribblers of stories. A holy baba for booklovers. Such is the provenance of his tradition of largesse, and may he live long, that those who have benefited from his wisdom and gentle guidance have gone on to become illustrious writers in their ow right and have in turn mentored others who are now inspiring yet another generation of writers. Not unlike a Sufi Qutab, he is reclusive, retiring, a hermit of few words, placid, and gleefully lost in his own labyrinths of tales ancient and modern. Those like myself who have had the pleasure and privilege of meeting him can vouch for his dry wit, his poetic and linguistic genius, and his astoundingly vast knowledge of global literature both acclaimed as well as obscure. The unique diction and penchant for themes of time, loss, nostalgia, antiquity, alienation, seasons and nature that characterize his distinctive and beautiful poetry also shines through in his prose.

Amongst the multiple gems in the newly minted volume my favourite is the sensual and dream-like Sagar aur Seerhian which merges joyful descriptions of childhood nostalgia with the growing anxiety of displacement and alienation, and chronicles a journey real, emotional and symbolic, whose purpose and precise destination are kept ambiguous and never fully delineated. So breathtakingly beautiful are the imagery and metaphors in this story that I frequently pause, pencil in hand, to fully savour them. This too is a ‘Story of Your Life’ — and it unravels a world where fear quietly opens the window shutters and peeks in like a cat at a half-asleep child; port lights in the night appear like darkness sewn together with a shining thread; a sinister old woman silently approaches, gradually, like smoke; music awakens within ages past and unseeable; sleep lies indolently, curled up, layer upon layer; grey smoke climbs and spreads through the sky like a vine; thoughts come to the mind like dry leaves caught up in a whirlwind, dancing; memories suck one in like a whirlpool; leaves fly about on the road in the autumn eve, like stories; and, on the horizon specks of light rotate gently, linger and disappear, like a lullaby. So richly textured is this story, so redolent in its visual depiction, and so wistful in capturing the rich tapestry of joys, longings, uncertainty and the ultimate culmination in enigmatic nothingness that is our life, that as a writer I see myself returning to it often, for inspiration and for reflection.

While nostalgia also permeates stories like Neend ka Bachpan, snaring us with its charm like an ancient spell, others like Raakh are imbued with a deep sense of foreboding and abject helplessness. Raakh is actually a great example of the modernism that’s also so vibrant in Saleem sahib’s work. The story brilliantly conveys the impressions, experiences and sentiments of ordinary people — insignificant residents of the Global South — caught up in the midst of an apocalyptic nuclear war being waged between the great powers.

Waqt Pighalnay ki Raat is one of the most haunting stories I have read about the horrors of Partition. It’s description of phantom hordes of massacred and violated migrants, silently treading through the night in the border countryside, shall long remain etched in my memory. Others like Siberia depict the mundaneness of everyday lives, enlivened by longings for the distant, the fabled and the extraordinary, which are ultimately unachievable. Ba Khabar, Bai Khabar on the other hand dissects exploitative mediocrity in the literary world with sharp observation, humour and abiding pathos. Awazain on the other hand is a melancholic and touching reflection on solid marital companionship, approaching old age and the ingratitude of neglectful offspring. Then there is the surreal Rozgar with its aliens embedded in human society who love to consume arhar ki dal; a story with such a wonderfully different mood and tone. We also have astute and irreverent social satire with a violent twist in Bai Kar Mabash. And then there are others that would well please Poe as well-crafted tales of mystery and imagination, such as Muamma and Muaqay. Sifarshi on the other hand subtly and humorously divulges how ordinariness can cloak extra-ordinariness.

The two dramas in the collection stand out for the spontaneity and sharpness of their dialogue. Professor Nafarman Khan Ki Machine is a science fiction story about a machine that takes your troubles away. The well-intentioned inventor soon realizes that how much more complex humans are than what we are willing to give them credit for. It is, however, the second drama Bees Baras Baad which brilliantly creates a dystopia brought about by overpopulation and drastically shrunk living space that I found very impactful and disturbing. Perhaps it is because the world that it creates is so familiar and relatable and yet so shocking.

One’s delight at finding Novel kai Chand Auraq in this volume is mingled with longing for the completed work. But I dare to still hope. What we do have with us offers great insight into Saleem sahib’s love of nature as an escape, a rejuvenator, and a healer, and his wonderfully evocative descriptions and eye for detail. The passages describe amongst other things a jungle covered hill with the remains of ruin. Lovingly bringing to life its plant, animal and bird life as well as its topography and interplays of light and shade, Saleem sahib conjures a magical space. A space overgrown with multi-coloured variegated foliage and enveloped by a verdurous intoxication, with veined roots stealing water in the dark, green leaves drinking up the sunshine, and a bewitching solitude. A dark forest from ancient tales whose paths led to the underworld, with filtering sun light resting in patches, pieces and bands on the forest floor; with motes aquiver and cobwebs sparkling in the pillars of light. This is writing for the pure pleasure of writing. Delight drawn from words like nectar that in turn sweetens our lives and allows us to carry on living despite all that is intent on embittering them. It is also writing that restores one’s faith in the written word to elevate us from the sordid and the mundane and to dream of better days and better places. An ambrosia that we owe to such sublime tellers of tales such as the one who dwells beyond the enclosed deep shadows of Shalimar Gardens, like a beneficent guardian spirit of the devotees of the written word.