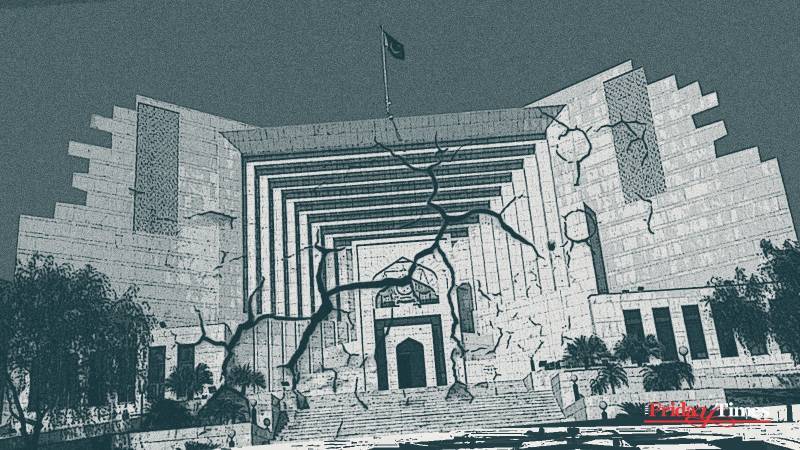

For any prosperous nation, a robust executive, legislative, and judicial system is essential. Developed countries have established sophisticated judicial frameworks, exemplified by nations like the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Denmark, where laws are upheld with stringent adherence and equality in adjudication. In Pakistan, however, justice often feels imbalanced, with laws applied differently depending on the social and economic status on whom it is being applied—a disparity that hinders national progress and undermines trust in the system.

True development, however, requires fair justice, and laws should be established to uphold equality, leaving no room for class-based discrimination.

For over four decades, the legacy of Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto awaited justice. His case, initially seen as a standard death penalty, was only recently acknowledged as a judicial murder. This recognition, although delayed, not only altered Pakistan’s historical narrative but also resonated globally.

By allowing judges from various regions to contribute, the judiciary would not only function more efficiently but also better reflect the diversity and needs of the Pakistani people

One major cause of delayed justice in Pakistan is the overburdened court system. The sheer volume of cases overwhelms the judiciary, leading to excessive wait times and impacting the quality of attention given to each case. Justice, therefore, is often delayed to the point where cases can stretch for years, leaving countless disputes unresolved.

The Senate of Pakistan sets a precedent by ensuring equal representation from all provinces, thereby creating a balanced legislative voice. Similarly, the judiciary would benefit greatly from an equal distribution of judges from each province, which could help reduce case backlogs and accelerate resolutions. By allowing judges from various regions to contribute, the judiciary would not only function more efficiently but also better reflect the diversity and needs of the Pakistani people.

A chief justice should focus solely on judicial responsibilities, avoiding political involvement or actions outside the court’s mandate. Past cases have shown that this line can blur, with one chief justice launched a public fundraising campaign for dam construction, raising concerns about the judiciary’s separation of powers. Another former chief justice appointed over 105 judges, later dismissing 103 of them unilaterally. Such actions disrupt established judicial protocols, as appointments should traditionally be made by the President. In one instance, when faced with opposition, the same judge threatened to reverse constitutional amendments if challenged—a stance that pressured members of Parliament to withdraw their criticism.

Now, more than ever, Pakistan needs a dedicated constitutional court. Such a court would not only uphold the judicial process but also improve justice accessibility across the nation. By incorporating judges from diverse backgrounds, it would more accurately represent the entire nation’s interests, fostering a more equitable and responsive legal system. Chairman PPP Bilawal Bhutto Zardari advocates strongly for this initiative, urging national support to establish a constitutional court as a democratic safeguard of the people’s rights and a cornerstone for justice in Pakistan.