The White Plague, a play written by the prolific Czech playwright, Karel Čapek and adapted into Urdu and English by the multitalented Meher Jaffri, was performed in Lahore Arts Council (Alhamra) from the 4th of September to the 8th. It was Zia Mohyeddin’s last commissioned play before his demise, and stays true to his legacy; it is riveting, fresh and negates the petulant cry of theatre being a dead medium. It was a roaring success, for a good reason– the play bridged the gap between the art and performance communities in Karachi and Lahore, offering a venue of shared collaborative love for storytelling.

Many call theatre a dwindling medium; one that has been overtaken by cinema. Yet, attending the opening and seeing the people come together through micro reactions– gasps, applause, cheers– makes one feel strangely giddy. At the end of the day, it is art that connects us all. And theatre, a medium since the days of Aeschylus and Shakespeare, is one that goes oft ignored.

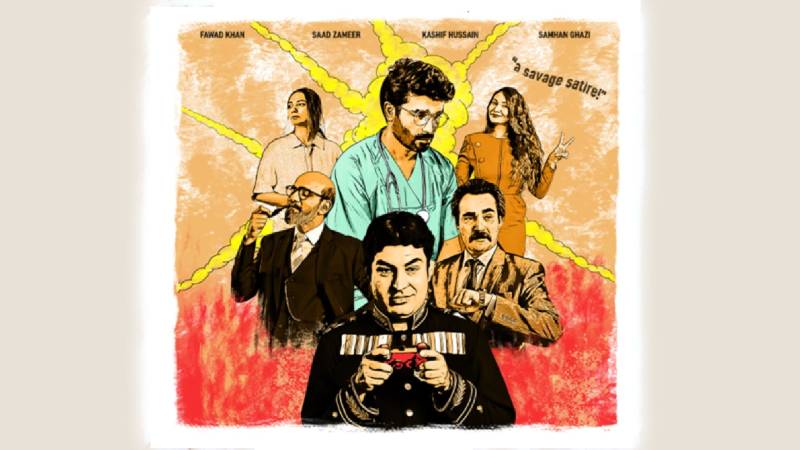

The adaptation stays true to the original story, while traversing timelines that gives it the wonderful, timeless feel of a story that (unfortunately) continues to repeat through history. We see a country marked by a deadly, leprosy-like pandemic that takes the lives of the elderly, causing the city to be an Oedipal reflection of Thebes. There is no Oedipus to solve the riddle, merely vultures that feast upon the main and misery; namely, the pompous Dr Sigelius (played by Fawad M Khan), the audacious Seth Sahib (played by Saman Ghazi) and the caricaturish-ly evil Marshal (played by Saad Zameer Khan). As the disease grips the city, a young doctor steps in to save it from the clutches of disease, brutality and war that the Marshal poses as a necessity for the greatness of his nation. Dr Galen (played by Kashif Hussain), the namesake of the great Greek physician that dominated conversations about anatomy and medicine for 1,300 years, poses a threat; either stop the war, or die without the cure. He reminds of the couplets of Nasir Kazmi, written during a savage military dictatorship:

“Bazaar bandd, raastay sunsaan, becharagh,

Woh raat hai keh gharr se nikalta nahee koi.”

I had the privilege of being in conversation with Meher before the play went live and discussing the journey that made it what it was. How inspiration struck her when she was sixteen, performing the play for the first time back in high school, and how the need to perform it in front of a larger audience solidified in her mind with the deadly pandemic that struck our lives in 2020. It is almost as if we have been left afloat in time, since then. I often wake up thinking it is 2019. I forget that six years have eclipsed past in the blink of an eye, and the reality of the dog-eat-dog world looms over me. What further strengthened the basis for her continuing this trajectory was the horror of genocide we witness, and how the world’s powers continually interject to defy peace. ‘War’ is a necessity. Lives lost will fade as the list grows, who is to think of them? The conversation left me hopeful and excited but also mildly bemused; these were a lot of wonderful ideas to present on stage, but would it be in a cohesive manner? Would it stay true to its purpose? How would it translate to an audience that already had a dwindling attention span– as a PSA against the military-industrial complex, or something that would jolt them? We agreed in the conversation that the live energy of theatre was much more palpable than the distance of cinema. I went with my hopes up, and I am overjoyed that they were cemented after the live performance.

The incorporation of multimedia is fantastic; it combines two forms of media, and as Meher previously mentioned in an interview, reels in the younger audience

The opening scene for the play was jarring, heightened by the ambient red lights that cast a deathly glow, combined with the sound design that loomed over the audience– the scene is defined by body bags and skulls littering the stage as a man groans, and then screams in pain. The first scene sets the tone for the rest of the play: “I’ve only seen poverty. What is He like, the one that takes his anger out on the poor?” the trembling voice says, punctuated with screams and a spectacular costume and makeup design. It chilled me to the core. It glowered over the audience like the Shakespearean depiction of the witches in Macbeth, as they scheme and toil, yet so much more physical than metaphysical.

The themes that the play discusses are so pertinent to our current times. The capitalist world, and how it sees death with indifference, as long as the motivations are for profit. The echo chasm that academia is; especially science and medicine adjacent academia, where the poor are treated as lab rats in the race to save the rich. Diseases serve as a source of morbid interest, as presented in the sheer glee Sigelius expresses as he discusses the symptomatology of the plague; revenue and research are his shrine. You have the precision of a medical professional in him, the semantics too, yet none of the empathy. The scenes in his office are humorous, yes, but depressing too.

The incorporation of multimedia is fantastic; it combines two forms of media, and as Meher previously mentioned in an interview, reels in the younger audience. The media is highlighted as holding hands, too often, with fascist propaganda. “What have the rich done to you?” a reporter scoffs at Galen in the play at some point. Censorship, surveillance and control are highlighted by a 4th wall break that rings out with calls for peace, almost immersive, as scenes of death and destruction play on screen. It is brilliant, all around.

The thing that cemented the play for me as one of the best I’ve experienced is the nuance that all the actors had, whether they played a major role or a minor role– many of them playing double roles, yet I was slightly shaken to realise that. The acting held you riveted, and the humour shone through without it being disconcerting in reference to tragedy.

It is almost as if it took them a snap of their fingers to completely transform into different individuals as they took on other characters– Saman Ghazi’s depiction of both the Father and the Seth stood out to me for this reason. He performs the role of the squeaky, high-pitched Father that is an accountant and incredibly self-absorbed. He shows the privilege of the petit bourgeois that shut their eyes and sew their lips when met with the world tumbling down on them; they think their fingers are closer to touching the simulation constructed by the bourgeois than to falling victim to their greed and being destroyed in the process. The Seth is a sombre, serious man– one that is still strangely principled, as he creates weapons of mass destruction while being funded by the Marshal. His death is the nail in the coffin that picks apart the world of the play brick by brick.

The Marshal’s character is wonderfully depicted; I enjoyed the fact that he lacked subtlety. Evil and greed, especially when it reaches a boiling point, is rarely courteous. We see it plastered across our screens all day, evil that fixates on others being subhuman to further its purpose. It is no surprise that Hitler was the inspiration behind the character in the original play, but I’d say it translates incredibly well into the current era and political climate. We watch the military-industrial complex in its death throes, as it inevitably rips off the mask that blinds all to its evil. I did, at points, notice people drift away from the Marshal’s evil monologue; the reason, I deduce, being how overwhelmed we already are by such depictions of evil not in fiction, but in reality. It was then his fall that piqued their interest; there was a collective glee in watching this evil man fall– and maybe the realisation that if one evil dies, another evil stands up to take his place– made it all the more striking. It is not an individual that is evil, alone; it is the very system that bolsters fascism that must be dismantled. Saad Zameer was excellent in his depiction, and always has been in the myriad of roles I have seen him in.

Kashif Hussain blew me away as Dr Galen; it is the little ticks and emotions behind his character. He flinches when voices are raised, stumbles, yet remains righteous and maintains the strength of his morals. He might cast a shell over himself to protect himself from the violence that surrounds him, yet he does not let it overpower his strong sense of self, his oath to serve. His desperation, his goodness of heart and soul is what makes him such a powerful character and it is all the more highlighted by Kashif’s acting. What could be a generically ‘good’ man, becomes a good man with a past. He seems to exist not for the 2 hour run of the play, but across time and across reality. He yells, and screams out in front of a camera in one of the most striking scenes to me: “You have the right to self-defence, not to violence. Stop it! Destroy these weapons.” Conversation with him was very enlightening; he explained how he had concocted a backstory for the character to play him as he was played, based on a brief mention in the script of him having lost all in the war. “He is traumatised,” he explained, “which explains the flinching and cowering. He lacks social cues too, yes. His desperation is fueled by his need for good in the world; he can’t believe people can be as wretched as they are, or harm someone trying to strive for the goodness of all. Which ultimately explains his end.”

However, the showstopper has to be Dr Sigelius’ character, played by Fawad M Khan. Sigelius is a pompous, wretched man, and god, did the audience love this pompous, wretched man. He is full of himself, incredibly elitist, an active participant of the military-industrial complex that actively uses medicine as a tool in the machine. Absolutely insufferable, yet so brilliantly done. It is as if Dickens himself wrote the caricaturish representation of the monocle-wearing, prideful colonial doctor that nags away at all that comes in his path. It somehow lessens the blow of his insidious ways, yet that is what makes it stand out all the more. He explained how he formed the character: “Meher and I discussed it, and made him a comic character. He is a show-off, full of himself, he is full of a sense of aesthetics, while maintaining a softness. We tried a couple of variations; a short tempered, angry old man. Yet that didn’t translate as well. It was through a process of performances too, 5-6 of them.”

On an ending note, I had several enlightening conversations with the audience– they were delighted as audience. Attendees included Salman Shahid, who had compliments for the cast as well as writer and director, Gohar Rasheed, Shahid Nadeem of Ajoka Theatre, Sarah Rashid, who recently took charge of Alhamra Arts Council and FS Aijazuddin.

I can’t stress it enough; how much we need stories that intersect with the utter depravity of what we see, what we feel, and what we hope to do. Satire that takes apart the cogs in the machines, overgrown with rot. If something exists that can save us, as humans, it is community and connection through art and literature. The White Plague is a wonderful step into this territory.