The story of how the aggrandisement of the British East India Company spread its tentacles all over India using brute power, intrigues and falsification of facts is these days being revisited with renewed vigour and painstaking research. We know that in 1857 finally things came to a head and a popular uprising took place in many parts of India against British rule, but already in the second half of the 18th century, a resistance movement had started taking shape.

One such book published recently is The Lost Hero of Banaras: Babu Jagat Singh by HA Qureshi and Shreya Pathak. It has as its backdrop the decline of the Mughal Empire as well as that of the Kingdom of Awadh and other native rulers – when the East India Company becoming the de facto ruler of much of India.

The fact that Jagat Singh respected the faiths of all his subjects means that a composite culture existed long before this term began to be used in modern parlance

In such a background the travails of Babu Jagat Singh to succeed to the position of the Raja of Banaras are examined in detail. Jagat Singh’s claims were set aside in favour of a more plaint and obsequious cousin Chait Singh, and later upon his death a descendant from the maternal line instead of Jagat Singh who belonged to the paternal line was made the Raja of Banaras. Such a decision was contrary to the established praxis of both Hindu and Islamic law, which applied in those times. The British did grant Jagat Singh a modest estate in Banaras, but not the coveted title of Raja.

Title: The Lost Hero of Banaras: Babu Jagat Singh

Authors: HA Qureshi and Shreya Pathak

Publishers: Primus Books, Delhi

Year: 2024

We learn that it was not simply a notorious case of highhanded tactics of seating and unseating Rajas and Nawabs on entirely arbitrary grounds, but a long-term strategic policy to target those native rulers who practised enlightened policies towards their subjects and who had the temerity to act in an upright manner vis-à-vis the Company government.

Jagat Singh not only established a Shiv mandir but also a mosque. Recently when I was in Banaras, I had the privilege of visiting both, which were functioning for devotees. In fact the mosque was built earlier than the mandir. One could read plaques in Persian and Sanskrit mentioning that Jagat Singh has bestowed his land as a service to the people who lived on his estate. It was Ramadan, so when we arrived it was time for taravia prayers. He had even donated land to build a Sikh gurdwara which could not be completed in his lifetime and since then has been the subject of some litigation.

The fact that Jagat Singh respected the faiths of all his subjects means that a composite culture existed long before this term began to be used in modern parlance to underscore the unity of all peoples and communities of India. This is true of the distinctive cultural ethos of the subcontinent and its roots can be traced to the established custom of the ruler being considered in principle the protector of all communities.

Jagat Singh continued to protest the injustice done to him by the British who exercised suzerainty over north India as well as Bengal and south India. His persistence to get justice irked the Company officers who in retaliation accused him of starting excavation in 1787 and stealing and destroying Buddhist relics from nearby Sarnath where the Buddha had begun his mission and converted his first five disciples.

The book seeks to set the record straight by examining a vast number of documents and other source material which has been collected with painstaking research. What the findings show is on the contrary – Jagat Singh stopped excavating as soon as he realised that site around Sarnath was once a Buddhist holy place. It is also shown that some of the relics which were reported missing by the British officers were stolen by their own colleagues.

In any event, in 1796 Jagat Singh was accused of assembling men to plunder the treasury and seize guns at Sekrore by his enemies, which made the British institute an inquiry against him. It was a period during which the British had intensified their power tactics to remove rulers who remained defiant which including the young Nawab of Awadh Wazir Ali. Armed clashes took place on 14th January 1799 between the forces assembled by Babu Jagat Singh and Wazir Ali and regular forces of the British Army. It established the precedent which was widely repeated in the great uprising of 1857 to make their venture as a forerunner to it.

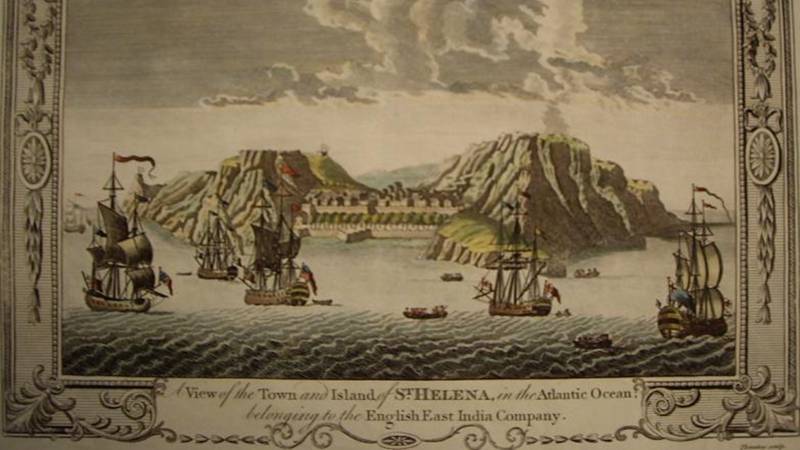

This was seized upon by the British and in a kangaroo court trial Jagat Singh was sentenced to death on 22 July 1799. It was later commuted to transportation for life to St. Helena. He was taken in a boat to embark a ship for transportation to that solitary island but when the boat reached the Ganga River Jagat Singh jumped into it and killed himself rather than accept the indignity of a life of a prisoner.

Thus, the first ripples of a resistance movement to the misrule of the English East India Company were already felt in the last decade of the 18th century.