In my article two weeks ago, I discussed the New Institutional Economic Theory. This school of thought emphasizes the role of institutions in economic history and political development. Rather than rejecting traditional neo-classical economic theory, it is simply reworked by bringing messy humans, and their institutions, into the elegant mathematical world of traditional theory.

The foundational principles of the new theory build on, modify, and extend neo-classical economic theory, by continuing its fundamental assumptions of scarcity and competition driven by choice. But the assumption of rationality that undergirds neo-classical theory is put aside and that automatically adds uncertainty - common to human exchange. Uncertainty requires human intervention and the core concept of the new theory is that humans create institutions to reduce the uncertainty in human exchange.

New Institutional Economics has added an entire new layer of theory on the nature of economies and societies. The theory postulates that institutions are created fundamentally to solve the problem of violence that would be endemic in human society without them. Since economic systems are based on scarcity and competition for resources, violence is certain unless constrained. Countries grant favored elites access to resources and to the rents they produce, and these elites minimize violence in order to maximize the rents, i.e. the extra amount earned by (or unearned income from) a resource. Most countries are considered Limited Access Orders (LAOs) because they ration access to the rents by fiat. Many of the developed countries have transitioned to Open Access Orders (OAOs), which work out access to rents through open competition.

What follows is a brief history of Pakistan and Bangladesh as seen through the lens of this theory. The first period has two segments. The first, 1947 to 1958, was characterized by a constitutional crisis as the two units could not agree on what the formula should be for two sets of elites to divide access to rents. The constitution, the institution to solve that problem took almost 10 years to write, but proved unacceptable to the bureaucracy and military which really governed the country and was never implemented. In 1958 the military, with strong support from the bureaucracy, took overt control.

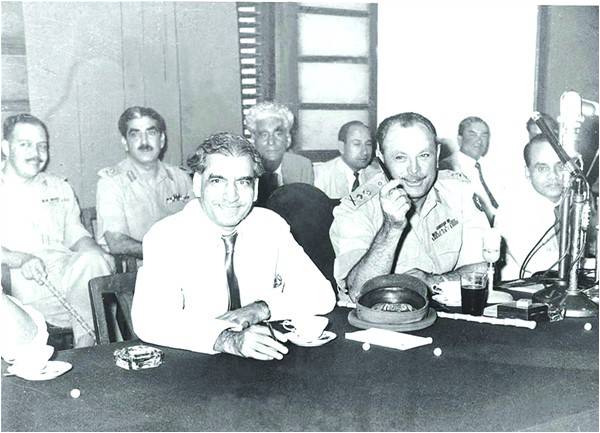

In the second segment, 1958 to 1971, the ruling coalition was dominated by West Pakistanis, with the military and the inherited bureaucracy in charge. Access to the rents went mainly to West Pakistani business houses. The interesting part is that this was justified under an ambitious development plan which aimed at creating a modern industrial base, so the rents went to those businesses thought capable of creating modern industries in new sectors. The state provided incentives - direct export subsidies, as well as indirect subsidies like an over-valued exchange rate, import controls - that created powerful incentives for investment. It was also hoped that an allocation of rents to the rural areas would help constrain violence, but the main deterrent was force. This dual strategy seemed to work for a while as economic growth was strong and, initially at least, there seemed more political stability. But, in retrospect, this appears to be a gigantic miscalculation as it underestimated the power of the excluded elites, most of them East Pakistani, to foster violence. And the very narrow basis of access to rents even in West Pakistan surely contributed to the uprising against Ayub Khan. The lesson here is that a basic LAO (the lower end of the developing country scale) will only be stable if the main potential organizers of violence are accorded access to rents. This becomes hard when resources are very scarce; thus force often becomes a necessity.

In 1972, Bangladesh separated from Pakistan in an orgy of violence. From 1972 to 1975 it was a populist authoritarian LAO that failed to quell the violence and provide stability primarily because it could not come close to satisfying the demand for rents by the numerous elite claimants that could generate violence. That manifestation disappeared after trying to impose rent discipline through a one-party state in yet another violent episode. This was succeeded by a government that looked much like the one that had ruled Unified Pakistan from 1958 to 1971, but there were crucial differences that allowed it to endure for 14 years. The military leaders used rent allocation to form parties which would compete for the rents. These allocations were negotiated individually with the government, and there were no set boundaries for the right to negotiate and/or join the government. Anybody could play if they had sufficient violence power and offered their fealty at a reasonable price. Similar to the Ayub Khan period, the military leaders opened up the system to rural elites, but did not rely on this to quell violence as the Ayub model had. Nor did they use rents in any deliberate way to execute a development plan. A significant amount of privatization took place which led to a substantial increase in a class of small capitalists. And Bangladesh got lucky as the leaders of this military clientistic state had the instinct to take advantage of the 1973 Multi Fibre Agreement, which had created what could be called “free rents,” garment manufacturers seeking a new home were brought together with the new Bangladeshi capitalists looking for investment opportunities.

In 1990, this military clientilistic LAO ran out of steam and was replaced by what seemed like a more stable and modern political system, one that could bring the country to the brink of prosperity and modernization in this century. This optimism has now abated as the government seems to be headed for another try at a one-party state and a return to an authoritarian LAO model that it tried in darker times over 40 years ago. It may work this time as the economy, led by the garment export industry, is going great guns, but the lessons from the previous try do not lend confidence. SOAS Economist Mushtaq Khan points out that such states require “either the military dominance of a leadership based on its control over a significant immediate flow of rents coming for instance from natural resources or…broadly based party organizations that offer [upward] career paths for organizers…,” i.e. a party organization that can hold out the prospect of access to rents from a growing real economy. While China’s example is appealing, the ruling party in Bangladesh is not in the same position, especially given that there remain opposing elites with the potential to create violence if shut out from access to economic rents.

And what would does the New Institutional Economic Theory have to say about contemporary Pakistan? To my knowledge the quantitative empirical work that is the heart of the theory has not been done. One can surmise, however, that after 1972, Pakistan’s elites were whipsawed by the rise of Zulfikar Bhutto, who would have given access to a whole new set of elites through his nationalization programs, and that his downfall was brought about when the elites of the previous regime, and their patrons (including the Army) were able to push back with strength. I imagine that under Ziaul Haq, Pakistan would have reverted to a military authoritarian LAO, with the same emphasis of using rents to spur investment in modern industries. Since 1988, Pakistan has probably been a combination of authoritarian and competitive clientelistic LAO, with some sort of unspoken but understood understanding (subject to change at short notice of course) between the military and the civilian governments as to the distribution of rents among their various clients. One thing that would run through Pakistan’s various versions of a LAO is that the ultimate deterrent to violence is surely force. These vague thoughts may be wildly off the mark, but the one certainty under this theory is that there are patrons and clients parceling out the economic rents in Pakistan as in all other LAOs.

The foundational principles of the new theory build on, modify, and extend neo-classical economic theory, by continuing its fundamental assumptions of scarcity and competition driven by choice. But the assumption of rationality that undergirds neo-classical theory is put aside and that automatically adds uncertainty - common to human exchange. Uncertainty requires human intervention and the core concept of the new theory is that humans create institutions to reduce the uncertainty in human exchange.

New Institutional Economics has added an entire new layer of theory on the nature of economies and societies. The theory postulates that institutions are created fundamentally to solve the problem of violence that would be endemic in human society without them. Since economic systems are based on scarcity and competition for resources, violence is certain unless constrained. Countries grant favored elites access to resources and to the rents they produce, and these elites minimize violence in order to maximize the rents, i.e. the extra amount earned by (or unearned income from) a resource. Most countries are considered Limited Access Orders (LAOs) because they ration access to the rents by fiat. Many of the developed countries have transitioned to Open Access Orders (OAOs), which work out access to rents through open competition.

What follows is a brief history of Pakistan and Bangladesh as seen through the lens of this theory. The first period has two segments. The first, 1947 to 1958, was characterized by a constitutional crisis as the two units could not agree on what the formula should be for two sets of elites to divide access to rents. The constitution, the institution to solve that problem took almost 10 years to write, but proved unacceptable to the bureaucracy and military which really governed the country and was never implemented. In 1958 the military, with strong support from the bureaucracy, took overt control.

In the second segment, 1958 to 1971, the ruling coalition was dominated by West Pakistanis, with the military and the inherited bureaucracy in charge. Access to the rents went mainly to West Pakistani business houses. The interesting part is that this was justified under an ambitious development plan which aimed at creating a modern industrial base, so the rents went to those businesses thought capable of creating modern industries in new sectors. The state provided incentives - direct export subsidies, as well as indirect subsidies like an over-valued exchange rate, import controls - that created powerful incentives for investment. It was also hoped that an allocation of rents to the rural areas would help constrain violence, but the main deterrent was force. This dual strategy seemed to work for a while as economic growth was strong and, initially at least, there seemed more political stability. But, in retrospect, this appears to be a gigantic miscalculation as it underestimated the power of the excluded elites, most of them East Pakistani, to foster violence. And the very narrow basis of access to rents even in West Pakistan surely contributed to the uprising against Ayub Khan. The lesson here is that a basic LAO (the lower end of the developing country scale) will only be stable if the main potential organizers of violence are accorded access to rents. This becomes hard when resources are very scarce; thus force often becomes a necessity.

In 1972, Bangladesh separated from Pakistan in an orgy of violence. From 1972 to 1975 it was a populist authoritarian LAO that failed to quell the violence and provide stability primarily because it could not come close to satisfying the demand for rents by the numerous elite claimants that could generate violence. That manifestation disappeared after trying to impose rent discipline through a one-party state in yet another violent episode. This was succeeded by a government that looked much like the one that had ruled Unified Pakistan from 1958 to 1971, but there were crucial differences that allowed it to endure for 14 years. The military leaders used rent allocation to form parties which would compete for the rents. These allocations were negotiated individually with the government, and there were no set boundaries for the right to negotiate and/or join the government. Anybody could play if they had sufficient violence power and offered their fealty at a reasonable price. Similar to the Ayub Khan period, the military leaders opened up the system to rural elites, but did not rely on this to quell violence as the Ayub model had. Nor did they use rents in any deliberate way to execute a development plan. A significant amount of privatization took place which led to a substantial increase in a class of small capitalists. And Bangladesh got lucky as the leaders of this military clientistic state had the instinct to take advantage of the 1973 Multi Fibre Agreement, which had created what could be called “free rents,” garment manufacturers seeking a new home were brought together with the new Bangladeshi capitalists looking for investment opportunities.

In 1990, this military clientilistic LAO ran out of steam and was replaced by what seemed like a more stable and modern political system, one that could bring the country to the brink of prosperity and modernization in this century. This optimism has now abated as the government seems to be headed for another try at a one-party state and a return to an authoritarian LAO model that it tried in darker times over 40 years ago. It may work this time as the economy, led by the garment export industry, is going great guns, but the lessons from the previous try do not lend confidence. SOAS Economist Mushtaq Khan points out that such states require “either the military dominance of a leadership based on its control over a significant immediate flow of rents coming for instance from natural resources or…broadly based party organizations that offer [upward] career paths for organizers…,” i.e. a party organization that can hold out the prospect of access to rents from a growing real economy. While China’s example is appealing, the ruling party in Bangladesh is not in the same position, especially given that there remain opposing elites with the potential to create violence if shut out from access to economic rents.

And what would does the New Institutional Economic Theory have to say about contemporary Pakistan? To my knowledge the quantitative empirical work that is the heart of the theory has not been done. One can surmise, however, that after 1972, Pakistan’s elites were whipsawed by the rise of Zulfikar Bhutto, who would have given access to a whole new set of elites through his nationalization programs, and that his downfall was brought about when the elites of the previous regime, and their patrons (including the Army) were able to push back with strength. I imagine that under Ziaul Haq, Pakistan would have reverted to a military authoritarian LAO, with the same emphasis of using rents to spur investment in modern industries. Since 1988, Pakistan has probably been a combination of authoritarian and competitive clientelistic LAO, with some sort of unspoken but understood understanding (subject to change at short notice of course) between the military and the civilian governments as to the distribution of rents among their various clients. One thing that would run through Pakistan’s various versions of a LAO is that the ultimate deterrent to violence is surely force. These vague thoughts may be wildly off the mark, but the one certainty under this theory is that there are patrons and clients parceling out the economic rents in Pakistan as in all other LAOs.