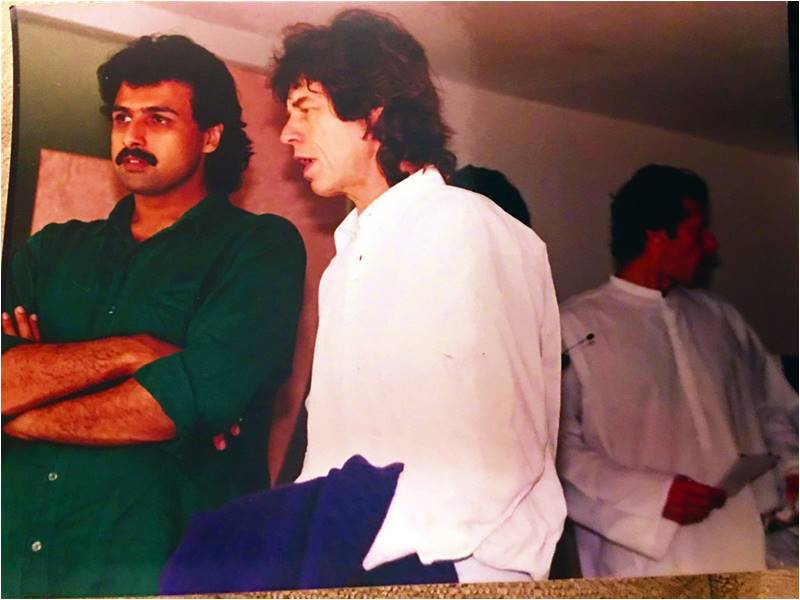

I’m not a cricket fan. Chances are you’re not a fan of tumour removal video playlists on Youtube, but here we are. The closest I got to being a cricket fan was when I saw Mick Jagger at the urinal during the 1996 World Cup Final held in Lahore. Athough I didn’t personally know who he was, his fame was obvious to everyone else, and his presence impressed me enough to look kindly on cricket, if for no other reason than its celebrity fan-base.

Since then cricket has evolved so much that I don’t think I can catch up even if I tried. One cannot simply ask questions like “What’s an ‘over’ exactly?” without getting some blowback. But despite my practiced apathy, every time the Cricket World Cup comes around I feel an excited little jerk in my stomach; a dormant, pre-verbal kind of hope, the kind that we as a nation have had to extinguish so many times over the years that it hardly flickers anymore. But it’s there. We could win, it suggests. We’ve done it before.

From what I have gathered, we didn’t win and consequently a lot of people are very angry at the cricket team. As I was reading what went down during those matches, what became clear was not how we lost, but rather how we approach winning. All the of write-ups I read about the Pak team focused on their strength but also overwhelmingly on their unpredictability. They spoke about how they can play well one day and poorly the next, as if Pakistan’s performance were tethered to chance, not talent. Once we exited the tournament is when I really began to see the way Pakistanis think about our national teams, most succinctly illustrated by the recently ubiquitous phrase “We deserved to be in the semi-final!”

No, we didn’t. Had we deserved to be in the semi-final, we would have known about it by having beaten the other team. If my middle-school trauma taught me one lesson it was this: performance dictates advancement in sport. That’s sort of the point of it. To be honest, if any one “deserved” to go through it was a country like Afghanistan, which we can all agree has had a rough set of decades. But in that one word - “deserved” - I saw a whole way of thinking prevalent in our culture, and it’s one that isn’t simply focused on cricket.

“Deserved” betrays an underlying assumption that winning has more to do with fate than resources, training, or leadership. When defeated (in cricket, football, finance, life) Pakistanis often say we were robbed, as if our victory was a sure thing derailed by nefariously talented phantom adversaries. If we win, we celebrate with a maniacal abandon all while not really knowing for sure if we could ever replicate those results. In a way this kind of thinking comes from self-preservation: in a country where so few people do make it big solely on the back of hard work and talent, it seems nearly fair that we should view all competitions as rigged unless we win them. It seems plausible that we, even subconsciously, believe that it is divine intervention and not stellar sports management that will see us through. But dig deeper, and that way of thinking goes from self-preservational to self-destrcutive – because entertaining our delusions means we don’t have to think about what really needs to be changed. And that just leads to more delusions.

I met a friend this week who is a scientist in Pakistan, and works as the head of a very prestigious set of labs. While she was telling me about the interesting work they are doing, she veered back into her first week on the job. Fresh from years in clinically-run English laboratories with strict guidelines and codes, she was still adjusting to life in a Pakistani hospital when she opened a temperature-controlled case to take out some highly infectious bio samples. There, in what was meant to be a sterile environment, she noticed a small styrofoam box. A man leaned over her and scooped it up nonchalantly.

“What is that?” my friend asked.

“It’s biryani,” he said, opening the box to show the rice.

“But,” she began, shocked. “but – that’s supposed to be an airtight sterile case!”

“Yes, but it’s also the perfect temperature...”

She was telling me the story as an illustration of the different standards we ourselves uphold when it comes to anything to do with Pakistan. And it isn’t only Pakistanis. I’ve heard the same sentiment about their own people from Brazilians, Indians, Egyptians, Italians, Moroccans, South Africans, Thai, Indonesians and so many more. The citizens of every developing nation probably feel this way at some point, particularly when the surroundings don’t always reflect their ambition or abilities. They all have the abilities, as do we. Maybe that’s why its scary to look facts squarely in the face and realize that in order to win hard (at anything) we would have to work hard. But that means changing how we’ve done things, which we are not great at.

It may be kind of funny to think of a Pakistani technician unbothered enough to store his lunch in a sterile environment, but the story is less cute when you remember they were storing virus samples in there.

So let’s be better. And if we can’t be better, let’s figure out why and not just refuse to ask difficult questions because it may require us to change too many things. Acknowledging the truth - about the lack of infrastructure around our national teams, or budget, or leaders - let’s us have a shot at changing it for the better. And if we do, then, well, who knows? You, too, could be peeing next to Mick Jagger in four years. Heaven willing!

Since then cricket has evolved so much that I don’t think I can catch up even if I tried. One cannot simply ask questions like “What’s an ‘over’ exactly?” without getting some blowback. But despite my practiced apathy, every time the Cricket World Cup comes around I feel an excited little jerk in my stomach; a dormant, pre-verbal kind of hope, the kind that we as a nation have had to extinguish so many times over the years that it hardly flickers anymore. But it’s there. We could win, it suggests. We’ve done it before.

In that one word - “deserved” - I saw a whole way of thinking prevalent in our culture, and it’s one that isn’t simply focused on cricket

From what I have gathered, we didn’t win and consequently a lot of people are very angry at the cricket team. As I was reading what went down during those matches, what became clear was not how we lost, but rather how we approach winning. All the of write-ups I read about the Pak team focused on their strength but also overwhelmingly on their unpredictability. They spoke about how they can play well one day and poorly the next, as if Pakistan’s performance were tethered to chance, not talent. Once we exited the tournament is when I really began to see the way Pakistanis think about our national teams, most succinctly illustrated by the recently ubiquitous phrase “We deserved to be in the semi-final!”

No, we didn’t. Had we deserved to be in the semi-final, we would have known about it by having beaten the other team. If my middle-school trauma taught me one lesson it was this: performance dictates advancement in sport. That’s sort of the point of it. To be honest, if any one “deserved” to go through it was a country like Afghanistan, which we can all agree has had a rough set of decades. But in that one word - “deserved” - I saw a whole way of thinking prevalent in our culture, and it’s one that isn’t simply focused on cricket.

“Deserved” betrays an underlying assumption that winning has more to do with fate than resources, training, or leadership. When defeated (in cricket, football, finance, life) Pakistanis often say we were robbed, as if our victory was a sure thing derailed by nefariously talented phantom adversaries. If we win, we celebrate with a maniacal abandon all while not really knowing for sure if we could ever replicate those results. In a way this kind of thinking comes from self-preservation: in a country where so few people do make it big solely on the back of hard work and talent, it seems nearly fair that we should view all competitions as rigged unless we win them. It seems plausible that we, even subconsciously, believe that it is divine intervention and not stellar sports management that will see us through. But dig deeper, and that way of thinking goes from self-preservational to self-destrcutive – because entertaining our delusions means we don’t have to think about what really needs to be changed. And that just leads to more delusions.

I met a friend this week who is a scientist in Pakistan, and works as the head of a very prestigious set of labs. While she was telling me about the interesting work they are doing, she veered back into her first week on the job. Fresh from years in clinically-run English laboratories with strict guidelines and codes, she was still adjusting to life in a Pakistani hospital when she opened a temperature-controlled case to take out some highly infectious bio samples. There, in what was meant to be a sterile environment, she noticed a small styrofoam box. A man leaned over her and scooped it up nonchalantly.

“What is that?” my friend asked.

“It’s biryani,” he said, opening the box to show the rice.

“But,” she began, shocked. “but – that’s supposed to be an airtight sterile case!”

“Yes, but it’s also the perfect temperature...”

She was telling me the story as an illustration of the different standards we ourselves uphold when it comes to anything to do with Pakistan. And it isn’t only Pakistanis. I’ve heard the same sentiment about their own people from Brazilians, Indians, Egyptians, Italians, Moroccans, South Africans, Thai, Indonesians and so many more. The citizens of every developing nation probably feel this way at some point, particularly when the surroundings don’t always reflect their ambition or abilities. They all have the abilities, as do we. Maybe that’s why its scary to look facts squarely in the face and realize that in order to win hard (at anything) we would have to work hard. But that means changing how we’ve done things, which we are not great at.

It may be kind of funny to think of a Pakistani technician unbothered enough to store his lunch in a sterile environment, but the story is less cute when you remember they were storing virus samples in there.

So let’s be better. And if we can’t be better, let’s figure out why and not just refuse to ask difficult questions because it may require us to change too many things. Acknowledging the truth - about the lack of infrastructure around our national teams, or budget, or leaders - let’s us have a shot at changing it for the better. And if we do, then, well, who knows? You, too, could be peeing next to Mick Jagger in four years. Heaven willing!