Moving to Mumbai, India's business capital, after living in the power capital of New Delhi for more than two decades is not easy. From way of life to culture to people’s behaviour, the two cities are poles apart.

The only commonality between the two metropolises is the Jinnah House. In Mumbai, the residence of the founder of Pakistan Muhammad Ali Jinnah adorns Malabar Hills, near Maharashtra government secretariat. In New Delhi, it stands tall and neat on Dr APJ Abdul Kalam Road (Aurangzeb Road), opposite Gandhi Smriti, where India's freedom icon Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated in 1948.

Mumbaikars are unable to cope with open spaces in Delhi and Delhiites feel cramped in pigeonhole-like spaces in Mumbai. For me, as a journalist covering the parliament, it is surprising to learn that Sachin Tendulkar and Rekha, both nominated as MPs for the Upper House (Rajya Sabha), did not take the official lushly landscaped bungalows in New Delhi but opted to arrive in the capital city early in the morning, attend parliament sessions, and return to Mumbai the same evening. Mumbai-based liquor baron Vijay Mallya, an MP for many years, followed the same pattern – after attending a parliament session in Delhi he would return to Mumbai the same evening on his chartered plane.

A Mumbaikar friend often justified this extravagance, saying, "You Delhiwalas do not appreciate the importance of the sea and its soothing effect. We love the sea more than the open spaces of Delhi."

For a Delhiwala like me, moving to Mumbai was a culture shock. I realised Mumbai does not value power but money.

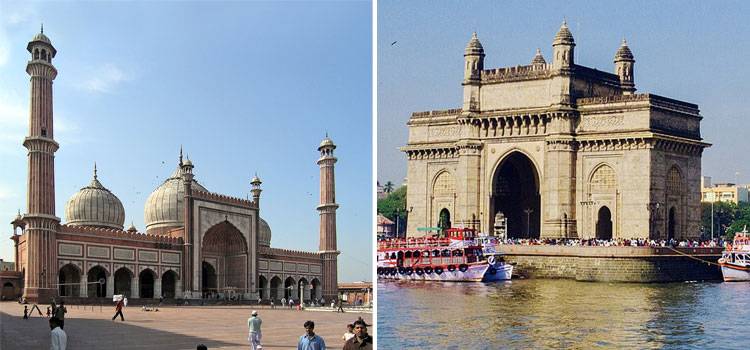

Delhi has been the political capital of South Asia for many centuries and has a rich historical and cultural heritage. Monuments from the time of the Pandavas, Khaljis, Tughlaqs, Lodhis, Mughals, Sikhs and British are everywhere. Whether it is Purana Qila, Qutub Minar or Gurudwara Rakab Ganj, Delhites live and breathe history.

Cultural Differences

If Delhi had Ghalib and Khusro, Mumbai had the proletarian Lokshahir (poet) Anna Bhau Sathe's Marathi Powada songs glorifying the traditional Marathi ballad tracing the history of Maratha.

Thus, the Ganga-Jamuna tehzeeb of Delhi, identified with Hindu-Muslim synergy, blends in Punjabi with Haryanvi and Bhojpuri, and gives a unique flavour to Delhi's language. Notwithstanding the slang borrowed from regions around Delhi, the language of Delhiwalas denotes respectful words. Mothers address their children with the Urdu-Hindi term, aap. In contrast, in Mumbai, where Marathi is the official language, the use of tum is common. Children address their parents with tum, as if they were addressing someone younger. In Delhi, however, tum is considered disrespectful.

Mumbai, with its swamps and creeks, is a city where different values merge and is heavily influenced by Parsi, Gujarati and Marathi cultures. Founded much later than Delhi, Mumbai has been a cosmopolitan city from the times of Portuguese and British in the 15th century. "It had the advantage of ports and was thus exposed to different cultures. Thanks to the ports, machinery could be imported from different parts of the world, which led to rapid industrialization. This led to the establishment of chawls, the indigenous cities of the colonial period," Mumbai-based architect and urban researcher Neear Adarkar tells The Friday Times.

The mills attracted Parsis and Gujarati investors and labour from the Konkan region, which straddles the west coast of Maharashtra, Goa and Karnataka. Later immigration from the southern states made Mumbai a region of many classes, religions, castes, and languages. The mill owners of Bombay soon began to enter various trades, with opium becoming a cash cow and money flowing into the economy.

Bombay's gross domestic product (GDP) today is estimated at around $368 billion, or about 6 percent of India's GDP. It is also home to the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE), one of Asia's oldest and largest stock exchanges, which plays a crucial role in the country's financial markets.

The chawls of Mumbai are not simply a form of mass housing. "Each chawl imported village characteristics into its neighbourhood. Along with dialects and idioms, cultural forms and performances, deities and temples, stores, goods, and restaurants from a particular area of origin established themselves in the specific localities," authors Sandeep Pendse, Neera Adarkar, and Maura Finkelstein write in their book, titled ‘The Chawls of Mumbai: Galleries of life’.

Ganesh Festival And Politics

In the 19th century, Lokmanya Tilak recognised the potential of these chawls and urged upper-caste Brahmins to hold a 10-day Ganesh festival to arouse nationalist fervour against the British. The tradition of holding this festival continues and shows how religion and politics can be woven into a festival.

In contrast, Delhi is clearly demarcated by the size of houses and the layout of villages. The city is planned and less cluttered.

Mumbai is an up-and-coming city. With a job to be done, a salary to be earned, exorbitantly high apartment rents to be paid for matchbox-sized houses, the expenses of living in the most expensive city of India keep residents on the move. The fast-paced lifestyle makes Mumbai the "city of dreams". People come to Mumbai to pursue dreams.

The city also has a vibrant nightlife, with numerous restaurants, bars and clubs open till late into the night, where women can move about alone without a sense of insecurity.

Delhi is a relatively relaxed city. It sleeps early. But citizens of this city, even if they use a more respectful language than Mumbaikars, quarrel over trivial matters – like shootouts over parking spaces in housing estates.

In Delhi, a Mumbaikar feels marginalised because last-mile connectivity is still a problem in much of the city, despite the introduction of the metro. "In Mumbai, you feel free. You have the freedom of mobility. You can hop in a cab or take a local train almost anywhere. In Delhi, you can get stuck," explains a journalist friend. From corporate CEOs to office workers, everyone prefers to take local trains to work.

Film Industry

Delhi is a political hub. Even a cab driver can give a crash course on the country's politics while driving passengers to their destination. The Mumbai cab drivers are clueless about current politics but authority on Bollywood.

Bombay, as the city used to be called, has been the centre of Indian film industry since 1910s. Studios and production houses make this port city that has attracted a diverse population, an ideal location for the film industry.

Bombay lent itself as a location for the Lumiere brothers' emissaries to project their moving images. In July 1896, the world's first successful moving picture was shot in Bombay, and the rest of India followed. "Ever since Dadasaheb Phalke shot his first silent film Raja Harishchandra (1913) in Bombay, the city surpassed other film production centres in the country in terms of overall infrastructure. From its film studios came mythical, fantastic, romantic, dancing and singing images that transported the nation to a dreamlike world," says film critic and historian Amrit Gangar.

Before the partition of the subcontinent, Bombay and Lahore were the two main centres of studios in the country. While Delhi suffered from the migrant crisis and struggled to provide basic necessities to them, Bombay opened its doors to artists, directors, producers and performers.

It is difficult for Delhi to break away from its feudal character, and its walls love tokens and favours. In Delhi, having little influence over others is considered power. Delhi is a city of jugaad, where everyone boasts of social and political connections.

Most Delhiwalas do not want to pay for a ticket to a concert or a play. They are looking for a free ticket. People in Mumbai appreciate hard work of others and play by rules. “Jugaad does not work in Mumbai," explains Dr Harish Bhalla, a New Delhi-based cultural historian.

Even though Delhi is one of the most popular cities for a variety of street foods, like kebabs, chole bhatura and chaats, Mumbai offers affordable food, like the iconic vada pav. The deep-fried potato cutlet stuffed in a bun became a popular food in Mumbai in 1960s. When Bal Thackeray was building his political party, Shiv Sena, in Maharashtra, vada pav was served to his volunteers and party cadres. It was easy to pack and transport, made one feel full, and was affordable. Its popularity and availability have increased over years.

Delhi, on the other hand, has been rebuilt, destroyed and rebuilt by rulers. Delhi is feudal, hierarchical and power-centred. "It lacks the middle ground, like vada pavs in Mumbai. There are either dhabas or five-star restaurants," Gangar sums up.

Despite my personal preference for Delhi, Mumbai stands out for its discipline and inclusive nature. A Mumbaikar will always stand in a queue and wait for his or her turn, on a bus, train, food court or mall. Breaking or jumping queues is not a part of Mumbai culture.

Although the national capital, people in Delhi live in ghettos. It is rare to see a woman in a burqa or hijab and a man in a skullcap in a mall, movie theatre or office outside the walled city of Delhi. But in Mumbai, you find pluralism and people of all religions and their symbols.

The only commonality between the two metropolises is the Jinnah House. In Mumbai, the residence of the founder of Pakistan Muhammad Ali Jinnah adorns Malabar Hills, near Maharashtra government secretariat. In New Delhi, it stands tall and neat on Dr APJ Abdul Kalam Road (Aurangzeb Road), opposite Gandhi Smriti, where India's freedom icon Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated in 1948.

Mumbaikars are unable to cope with open spaces in Delhi and Delhiites feel cramped in pigeonhole-like spaces in Mumbai. For me, as a journalist covering the parliament, it is surprising to learn that Sachin Tendulkar and Rekha, both nominated as MPs for the Upper House (Rajya Sabha), did not take the official lushly landscaped bungalows in New Delhi but opted to arrive in the capital city early in the morning, attend parliament sessions, and return to Mumbai the same evening. Mumbai-based liquor baron Vijay Mallya, an MP for many years, followed the same pattern – after attending a parliament session in Delhi he would return to Mumbai the same evening on his chartered plane.

A Mumbaikar friend often justified this extravagance, saying, "You Delhiwalas do not appreciate the importance of the sea and its soothing effect. We love the sea more than the open spaces of Delhi."

For a Delhiwala like me, moving to Mumbai was a culture shock. I realised Mumbai does not value power but money.

Delhi has been the political capital of South Asia for many centuries and has a rich historical and cultural heritage. Monuments from the time of the Pandavas, Khaljis, Tughlaqs, Lodhis, Mughals, Sikhs and British are everywhere. Whether it is Purana Qila, Qutub Minar or Gurudwara Rakab Ganj, Delhites live and breathe history.

The only commonality between the two metropolises is the Jinnah House. In Mumbai, the residence of the founder of Pakistan Muhammad Ali Jinnah adorns Malabar Hills, near Maharashtra government secretariat. In New Delhi, it stands tall and neat on Dr APJ Abdul Kalam Road (Aurangzeb Road), opposite Gandhi Smriti, where India's freedom icon Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated in 1948.

Cultural Differences

If Delhi had Ghalib and Khusro, Mumbai had the proletarian Lokshahir (poet) Anna Bhau Sathe's Marathi Powada songs glorifying the traditional Marathi ballad tracing the history of Maratha.

Thus, the Ganga-Jamuna tehzeeb of Delhi, identified with Hindu-Muslim synergy, blends in Punjabi with Haryanvi and Bhojpuri, and gives a unique flavour to Delhi's language. Notwithstanding the slang borrowed from regions around Delhi, the language of Delhiwalas denotes respectful words. Mothers address their children with the Urdu-Hindi term, aap. In contrast, in Mumbai, where Marathi is the official language, the use of tum is common. Children address their parents with tum, as if they were addressing someone younger. In Delhi, however, tum is considered disrespectful.

Mumbai, with its swamps and creeks, is a city where different values merge and is heavily influenced by Parsi, Gujarati and Marathi cultures. Founded much later than Delhi, Mumbai has been a cosmopolitan city from the times of Portuguese and British in the 15th century. "It had the advantage of ports and was thus exposed to different cultures. Thanks to the ports, machinery could be imported from different parts of the world, which led to rapid industrialization. This led to the establishment of chawls, the indigenous cities of the colonial period," Mumbai-based architect and urban researcher Neear Adarkar tells The Friday Times.

The mills attracted Parsis and Gujarati investors and labour from the Konkan region, which straddles the west coast of Maharashtra, Goa and Karnataka. Later immigration from the southern states made Mumbai a region of many classes, religions, castes, and languages. The mill owners of Bombay soon began to enter various trades, with opium becoming a cash cow and money flowing into the economy.

Bombay's gross domestic product (GDP) today is estimated at around $368 billion, or about 6 percent of India's GDP. It is also home to the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE), one of Asia's oldest and largest stock exchanges, which plays a crucial role in the country's financial markets.

The chawls of Mumbai are not simply a form of mass housing. "Each chawl imported village characteristics into its neighbourhood. Along with dialects and idioms, cultural forms and performances, deities and temples, stores, goods, and restaurants from a particular area of origin established themselves in the specific localities," authors Sandeep Pendse, Neera Adarkar, and Maura Finkelstein write in their book, titled ‘The Chawls of Mumbai: Galleries of life’.

Ganesh Festival And Politics

In the 19th century, Lokmanya Tilak recognised the potential of these chawls and urged upper-caste Brahmins to hold a 10-day Ganesh festival to arouse nationalist fervour against the British. The tradition of holding this festival continues and shows how religion and politics can be woven into a festival.

In contrast, Delhi is clearly demarcated by the size of houses and the layout of villages. The city is planned and less cluttered.

Mumbai is an up-and-coming city. With a job to be done, a salary to be earned, exorbitantly high apartment rents to be paid for matchbox-sized houses, the expenses of living in the most expensive city of India keep residents on the move. The fast-paced lifestyle makes Mumbai the "city of dreams". People come to Mumbai to pursue dreams.

The city also has a vibrant nightlife, with numerous restaurants, bars and clubs open till late into the night, where women can move about alone without a sense of insecurity.

Delhi is a relatively relaxed city. It sleeps early. But citizens of this city, even if they use a more respectful language than Mumbaikars, quarrel over trivial matters – like shootouts over parking spaces in housing estates.

In Delhi, a Mumbaikar feels marginalised because last-mile connectivity is still a problem in much of the city, despite the introduction of the metro. "In Mumbai, you feel free. You have the freedom of mobility. You can hop in a cab or take a local train almost anywhere. In Delhi, you can get stuck," explains a journalist friend. From corporate CEOs to office workers, everyone prefers to take local trains to work.

If Delhi had Ghalib and Khusro, Mumbai had the proletarian Lokshahir (poet) Anna Bhau Sathe's Marathi Powada songs glorifying the traditional Marathi ballad tracing the history of Maratha.

Film Industry

Delhi is a political hub. Even a cab driver can give a crash course on the country's politics while driving passengers to their destination. The Mumbai cab drivers are clueless about current politics but authority on Bollywood.

Bombay, as the city used to be called, has been the centre of Indian film industry since 1910s. Studios and production houses make this port city that has attracted a diverse population, an ideal location for the film industry.

Bombay lent itself as a location for the Lumiere brothers' emissaries to project their moving images. In July 1896, the world's first successful moving picture was shot in Bombay, and the rest of India followed. "Ever since Dadasaheb Phalke shot his first silent film Raja Harishchandra (1913) in Bombay, the city surpassed other film production centres in the country in terms of overall infrastructure. From its film studios came mythical, fantastic, romantic, dancing and singing images that transported the nation to a dreamlike world," says film critic and historian Amrit Gangar.

Before the partition of the subcontinent, Bombay and Lahore were the two main centres of studios in the country. While Delhi suffered from the migrant crisis and struggled to provide basic necessities to them, Bombay opened its doors to artists, directors, producers and performers.

It is difficult for Delhi to break away from its feudal character, and its walls love tokens and favours. In Delhi, having little influence over others is considered power. Delhi is a city of jugaad, where everyone boasts of social and political connections.

Most Delhiwalas do not want to pay for a ticket to a concert or a play. They are looking for a free ticket. People in Mumbai appreciate hard work of others and play by rules. “Jugaad does not work in Mumbai," explains Dr Harish Bhalla, a New Delhi-based cultural historian.

Even though Delhi is one of the most popular cities for a variety of street foods, like kebabs, chole bhatura and chaats, Mumbai offers affordable food, like the iconic vada pav. The deep-fried potato cutlet stuffed in a bun became a popular food in Mumbai in 1960s. When Bal Thackeray was building his political party, Shiv Sena, in Maharashtra, vada pav was served to his volunteers and party cadres. It was easy to pack and transport, made one feel full, and was affordable. Its popularity and availability have increased over years.

Delhi, on the other hand, has been rebuilt, destroyed and rebuilt by rulers. Delhi is feudal, hierarchical and power-centred. "It lacks the middle ground, like vada pavs in Mumbai. There are either dhabas or five-star restaurants," Gangar sums up.

Despite my personal preference for Delhi, Mumbai stands out for its discipline and inclusive nature. A Mumbaikar will always stand in a queue and wait for his or her turn, on a bus, train, food court or mall. Breaking or jumping queues is not a part of Mumbai culture.

Although the national capital, people in Delhi live in ghettos. It is rare to see a woman in a burqa or hijab and a man in a skullcap in a mall, movie theatre or office outside the walled city of Delhi. But in Mumbai, you find pluralism and people of all religions and their symbols.