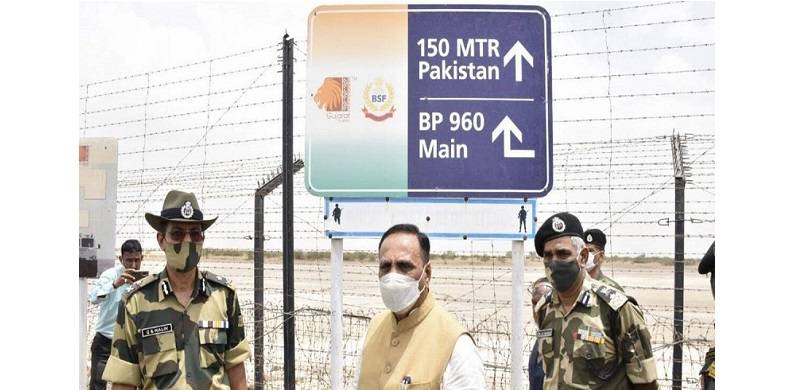

Every few weeks one reads that Pakistan and India have granted visas to religious pilgrims or built a special corridor for them at a time when all other exchange remains prohibited. These announcements are made with a certain sense of noblesse oblige as if a great favour were being bestowed. In a sense this reflects reality because our states do grant visas as favours. But this selectivity does raise a question that needs to be asked: why is religion privileged in this regard? What entitles it to special consideration?

The human identity is multidimensional, and religion is just one of its attributes. It is not even the most consciously considered one, being acquired passively at birth. People are born into a religion, and most are too lazy or incurious to examine if there might be a more attractive one on offer. Nor is there much incentive to do so, unlike, say, in the case of nationality, where one finds everyone, rich or poor, dying to swap theirs for a more beneficial alternative.

Neither can an interest in paying homage to the dead be uncritically considered to be of greater importance than interacting with the living; the latter may yield greater satisfaction to some. Why can’t one be granted a visa to pay homage to Lata Mangeskhar, a once-in-a-century artist, who has a quasi-religious following that, to its credit, rises beyond any particular ethnicity or faith or nationality?

Surely none, except the most simple-minded believe that religious people are somehow better than others. Leave aside the ones who are simply pretending to be religious – of which there are many. If the proposition were indeed true, our maulvis and priests and babas, steeped in religion, would be paragons of virtue. Are they?

Given the above, the question remains: why privilege religion? Those with the power to issue visas are unable to advance a convincing argument. Do they really believe that people not overtly religious or not wearing their religions on their sleeves - or for whom visiting religious sites is not a priority - are less deserving of consideration? Even if officials personally disapprove of a lack of interest in religious sites, is that reason enough for discrimination? Shouldn’t they be forced to reconsider their own position instead of passing moral judgement on the interests of others from the vantage point of their own unexamined prejudices?

Do they believe that those who take their religion lightly are morally deficient? They must be aware that in Europe half the population answers ‘None’ to their religious affiliation. Are all those people less moral than the rest? Should they be discriminated against on that account? If so, does Pakistan enquire about their religious affiliation and refuse them visas if they belong to the ‘None’ category?

More to the point: when a non-believing, pork-eating, dignitary visits Pakistan he/she is received at the airport with honour. Clearly, this is a situation in which religion is deemed an irrelevant attribute. So, why is it relevant for those living inside the country? Why do they have to declare their religion on their passports?

Those who are scared of questions wish to avoid them. Or, perhaps, they feel that encouraging questions would not be to their advantage. The argument is simple enough: just as a person with interest in religion considers a religious site to be special, an academic accords the same status to a university, an author to a festival of books, an artist to an exhibition, a musician to a conference, and a child to the place where his/her grandparents were born. Is there a flaw in this reasoning?

Nothing about religion makes it superior to other legitimate passions and interests. And one should be wary of justifying the illogical nature of the policy by reference to the impossibility of having any truck with the “enemy.” It would lead to a bigger absurdity. How is it alright to ban all exchange with the “enemy,” even that of books, while at the same time dying to play cricket with it? Why not forfeit a little match for such a grand resolve?

Not just that: how is it kosher for the same functionaries who deny visas to visit the “enemy” to dash off to see a game with it leaving behind self-ignited fires burning at home? Especially when, irony of ironies, the fires are lit by the very same religious people who would be first in line to be issued visas to pray across the border?

We live in religious times and are governed by pious people. But the slide down the corruption index continues unabated. On raising irreverent questions, we will be reminded that our religion enjoins thinking. This reminder basks in the security of knowing that religion is meant to be privileged rather than actually followed!

The human identity is multidimensional, and religion is just one of its attributes. It is not even the most consciously considered one, being acquired passively at birth. People are born into a religion, and most are too lazy or incurious to examine if there might be a more attractive one on offer. Nor is there much incentive to do so, unlike, say, in the case of nationality, where one finds everyone, rich or poor, dying to swap theirs for a more beneficial alternative.

Neither can an interest in paying homage to the dead be uncritically considered to be of greater importance than interacting with the living; the latter may yield greater satisfaction to some. Why can’t one be granted a visa to pay homage to Lata Mangeskhar, a once-in-a-century artist, who has a quasi-religious following that, to its credit, rises beyond any particular ethnicity or faith or nationality?

Surely none, except the most simple-minded believe that religious people are somehow better than others. Leave aside the ones who are simply pretending to be religious – of which there are many. If the proposition were indeed true, our maulvis and priests and babas, steeped in religion, would be paragons of virtue. Are they?

Given the above, the question remains: why privilege religion? Those with the power to issue visas are unable to advance a convincing argument. Do they really believe that people not overtly religious or not wearing their religions on their sleeves - or for whom visiting religious sites is not a priority - are less deserving of consideration? Even if officials personally disapprove of a lack of interest in religious sites, is that reason enough for discrimination? Shouldn’t they be forced to reconsider their own position instead of passing moral judgement on the interests of others from the vantage point of their own unexamined prejudices?

The argument is simple enough: just as a person with interest in religion considers a religious site to be special, an academic accords the same status to a university, an author to a festival of books, an artist to an exhibition, a musician to a conference, and a child to the place where his/her grandparents were born. Is there a flaw in this reasoning?

Do they believe that those who take their religion lightly are morally deficient? They must be aware that in Europe half the population answers ‘None’ to their religious affiliation. Are all those people less moral than the rest? Should they be discriminated against on that account? If so, does Pakistan enquire about their religious affiliation and refuse them visas if they belong to the ‘None’ category?

More to the point: when a non-believing, pork-eating, dignitary visits Pakistan he/she is received at the airport with honour. Clearly, this is a situation in which religion is deemed an irrelevant attribute. So, why is it relevant for those living inside the country? Why do they have to declare their religion on their passports?

Those who are scared of questions wish to avoid them. Or, perhaps, they feel that encouraging questions would not be to their advantage. The argument is simple enough: just as a person with interest in religion considers a religious site to be special, an academic accords the same status to a university, an author to a festival of books, an artist to an exhibition, a musician to a conference, and a child to the place where his/her grandparents were born. Is there a flaw in this reasoning?

Nothing about religion makes it superior to other legitimate passions and interests. And one should be wary of justifying the illogical nature of the policy by reference to the impossibility of having any truck with the “enemy.” It would lead to a bigger absurdity. How is it alright to ban all exchange with the “enemy,” even that of books, while at the same time dying to play cricket with it? Why not forfeit a little match for such a grand resolve?

Not just that: how is it kosher for the same functionaries who deny visas to visit the “enemy” to dash off to see a game with it leaving behind self-ignited fires burning at home? Especially when, irony of ironies, the fires are lit by the very same religious people who would be first in line to be issued visas to pray across the border?

We live in religious times and are governed by pious people. But the slide down the corruption index continues unabated. On raising irreverent questions, we will be reminded that our religion enjoins thinking. This reminder basks in the security of knowing that religion is meant to be privileged rather than actually followed!