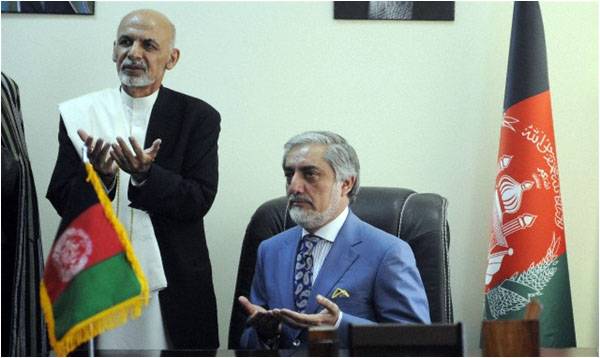

Last year’s presidential elections are being seen as a landmark event in the war ravaged history of Afghanistan. About 8 million people turned out to cast their votes despite threats of violence from the militant opposition, Tehreek-e-Taliban Afghanistan. The elections resulted in a compromise set-up with Ashraf Ghani being sworn in as president and his political rival Dr Abdullah Abdullah given the newly created slot of chief executive. Despite the encouraging signs, analysts predict a tough going for the national unity government in the months coming ahead.

“The 2014 presidential elections were indeed a historic event for Afghanistan, marking its first ever peaceful democratic transition of power,” says Muhammad Tahir Sabarai, advisor to the Afghan President on Tribal Affairs. “There is immense pressure on President Ashraf Ghani and Dr Abdullah Abdullah from within and outside the country to deliver on the promises they had both made during their election campaigns.” But making any real progress on any front is closely linked to the restoration of peace in Afghanistan, he says. “We are occupied with the question of peace and reconciliation with Taliban and we can only divert our energies to other aspects of governance once we succeed in bringing them to the negotiating table.”

According to Arifullah Pashtun, chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee of the Senate of Afghanistan, the unity government – a brave experiment in a country that is stranger to western democracy – is facing complex challenges such as fighting corruption, promoting economic development and pushing ahead with major reforms. Ghani has shown zero tolerance for corruption, he says, and his decision to reopen an investigation into the Kabul Bank scandal – in which the bank collapsed after major corruption by senior Afghan figures who stole close to $1 billion – is a step in that direction.

Professor Dr Sarfaraz, director of the Area Study Center, Central Asia, in Peshawar, agrees. Ashraf Ghani is serious about eliminating corruption, he says, and there have been no major allegations of corruption against the new government so far. There is also a complete synergy between Ghani and Abdullah on peace talks with the Taliban, he adds. “They are ready to talk to them, with active support of Pakistan, in order to bring them to mainstream.”

According to Senator Pashtun, Abdullah Abdullah is also mindful of the brutal fact that war will bring more misery to Afghanistan, and if a negotiated solution to the Afghan quagmire is not worked out, there is a possibility of the war spreading to the north of Afghanistan, which he represents.

“Although the Afghan National Unity Government has survived the initial hiccups and quite ably convinced the international community that their continued support and engagement in Afghanistan is crucial to their own national security and to regional and international peace, the official machinery is haunted by the question, ‘who is in charge’,” says Brig (r) Saad Muhammad, a former defence attaché at the Pakistan embassy in Kabul. “This certainly adds to the confusion and affects the overall working of the government which is yet to prove itself vis-a-vis good governance.” President Ashraf Ghani is a keen administrator, he says, and strictly follows deadlines – a trait that makes him a big misfit in the current set-up. According to Brig (r) Saad, Ghani is facing a hostile parliament which further complicates his stint as an Afghan president sharing powers with a chief executive which are yet to be defined by the Afghan constitution.

But according to Yousaf Ghaznavi, advisor to the Parliament of Afghanistan, Ghani and Abdullah have expressed, during the recent London Conference, their commitment to strengthen the unity government. Although only a third of the new cabinet members have been approved so far, he says, there is a general consensus between the two leaders on their cabinet. Similarly, they have only formally appointed three of the 34 governors so far. The rest are working as acting governors. “There is one important aspect to the delay in the nomination of the cabinet and governors,” he says. “The government may be waiting for Taliban’s response to the offer of peace talks, and they might be offered ministries or governorships as part of a negotiated settlement.”

“The 2014 presidential elections were indeed a historic event for Afghanistan, marking its first ever peaceful democratic transition of power,” says Muhammad Tahir Sabarai, advisor to the Afghan President on Tribal Affairs. “There is immense pressure on President Ashraf Ghani and Dr Abdullah Abdullah from within and outside the country to deliver on the promises they had both made during their election campaigns.” But making any real progress on any front is closely linked to the restoration of peace in Afghanistan, he says. “We are occupied with the question of peace and reconciliation with Taliban and we can only divert our energies to other aspects of governance once we succeed in bringing them to the negotiating table.”

Taliban may be offered ministries or governorships

According to Arifullah Pashtun, chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee of the Senate of Afghanistan, the unity government – a brave experiment in a country that is stranger to western democracy – is facing complex challenges such as fighting corruption, promoting economic development and pushing ahead with major reforms. Ghani has shown zero tolerance for corruption, he says, and his decision to reopen an investigation into the Kabul Bank scandal – in which the bank collapsed after major corruption by senior Afghan figures who stole close to $1 billion – is a step in that direction.

Professor Dr Sarfaraz, director of the Area Study Center, Central Asia, in Peshawar, agrees. Ashraf Ghani is serious about eliminating corruption, he says, and there have been no major allegations of corruption against the new government so far. There is also a complete synergy between Ghani and Abdullah on peace talks with the Taliban, he adds. “They are ready to talk to them, with active support of Pakistan, in order to bring them to mainstream.”

According to Senator Pashtun, Abdullah Abdullah is also mindful of the brutal fact that war will bring more misery to Afghanistan, and if a negotiated solution to the Afghan quagmire is not worked out, there is a possibility of the war spreading to the north of Afghanistan, which he represents.

“Although the Afghan National Unity Government has survived the initial hiccups and quite ably convinced the international community that their continued support and engagement in Afghanistan is crucial to their own national security and to regional and international peace, the official machinery is haunted by the question, ‘who is in charge’,” says Brig (r) Saad Muhammad, a former defence attaché at the Pakistan embassy in Kabul. “This certainly adds to the confusion and affects the overall working of the government which is yet to prove itself vis-a-vis good governance.” President Ashraf Ghani is a keen administrator, he says, and strictly follows deadlines – a trait that makes him a big misfit in the current set-up. According to Brig (r) Saad, Ghani is facing a hostile parliament which further complicates his stint as an Afghan president sharing powers with a chief executive which are yet to be defined by the Afghan constitution.

But according to Yousaf Ghaznavi, advisor to the Parliament of Afghanistan, Ghani and Abdullah have expressed, during the recent London Conference, their commitment to strengthen the unity government. Although only a third of the new cabinet members have been approved so far, he says, there is a general consensus between the two leaders on their cabinet. Similarly, they have only formally appointed three of the 34 governors so far. The rest are working as acting governors. “There is one important aspect to the delay in the nomination of the cabinet and governors,” he says. “The government may be waiting for Taliban’s response to the offer of peace talks, and they might be offered ministries or governorships as part of a negotiated settlement.”