“The public will be allowed to enter the National Stadium through gates number four, five, six and eight,” announced the DIG Traffic on the day of Abdul Sattar Edhi’s funeral in Karachi, before adding, without shame or irony: “The VIPs and VVIPs, most of whom will be coming from Defence, Clifton and Shahrah-e-Faisal, will enter through the main gate.”

The main gate for the rulers, the “other” gates for commoners. Business as usual in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, where doors are always being opened for the high and mighty.

But it is a testament to Abdul Sattar Edhi’s greatness, and to the tragedy of the country he leaves behind, that on the day of his funeral, Pakistan’s credibility-hungry generals and politicians were lining up behind his coffin to bask in some reflected glory.

Who was Abdul Sattar Edhi? A conventional timeline places him in a strife-ridden century: born in 1928 in what is now Indian Gujarat, this young Bantva Memon was deeply affected by his mother’s physical paralysis, and tended to her until her death when he was 19. After Partition, Edhi moved to Karachi and sold cloth in its wholesale market. But the panoply of afflictions in that migrant-heavy city appealed to his conscience: in the 1950s he set up a drug dispensary, then a makeshift hospital to treat victims of an influenza epidemic, then an ambulance service for the victims of the 1965 war with India. In the last thirty years of his life, as Karachi was wracked by ethnic and sectarian violence, Edhi’s duty-bound ambulances could be seen beeping from site to site, their red-and-white logo a hope-instilling icon of commitment and consistency.

For such a motivated man, Edhi was remarkably free of ambition. In fact it would be accurate to say that his life was one long exercise in self-abnegation. Famously “simple” and unfussy, Edhi sat on a wooden bench in his office, slept in a windowless room and drew no salary from his sprawling network of charities. He is said to have owned only two pairs of clothes when he died. In these Tolstoyan attempts at transparency and moral exactitude, this perpetually perturbed-looking, white-bearded nana (as he was called by the children in his orphanage) was steadfastly assisted by his wife Bilquis, who came to embody the virtues of patience and forbearance, the necessary sabr to his saadgi.

The accounts of acquaintances and journalists all conjure up a clear-eyed man, one who had no time for abstract or overly romantic ideas about poverty. “Never give to beggars,” he once told a wealthy philanthropist from Lahore. Another time, recalling the plight of people wounded in the 1965 war, he admitted, “My heart became so hard after that. I made humanity my religion and devoted my life to it.”

In the 1990s, he was approached by General Hameed Gul and Imran Khan for mercenary enlistment against Benazir Bhutto’s government. But Edhi refused to redeem their conspiracy with his participation, even when they threatened him with force. “They wanted to fire a gun from my shoulder,” he told an interviewer, “but I wouldn’t let them.”

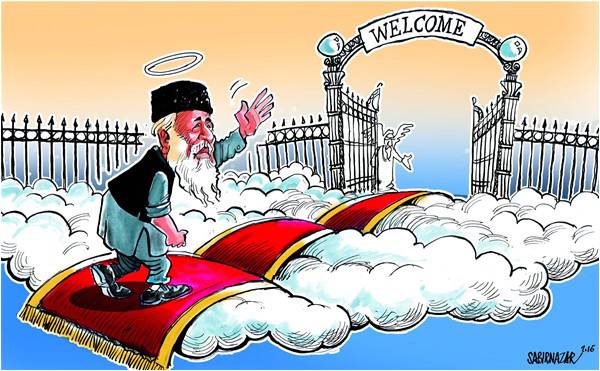

How might we assess the legacy of such a Spartan and singularly upright figure? First, by placing him in a long line of revolutionary ascetics, men whose renunciation of wealth and power bestowed on them a purifying aura of spiritual and moral authority. The Buddha, the Sufis, even Gandhi with his complicated engagement of colonial power, all rose to prominence through a paradoxical shunning of privilege; it was their symbolic embrace of poverty that became their capital, their nearness to suffering that elevated them in the eyes of a cynical and motive-wary public. For Abdul Sattar Edhi, who lived in a particularly turbulent time, and who witnessed first hand the toxicification of Pakistan’s religious fabric, that passage to sainthood was lined with the additional pitfall of the new-age missionary’s deceptive piety. Let us not forget that Edhi was operating his orphanages and soup kitchens in the age of Jamaat-ud-Dawa and other insidious “charities” whose bright and shiny aid programs are often fronts for hate-filled recruitment drives. Indeed, let us uphold Edhi’s stance on religious discrimination as reformist and exemplary: “There were many who asked me, ‘Why must you pick up Christians and Hindus in your ambulance?’ And I said, ‘Because the ambulance is more Muslim than you.’”

In one of his last interviews, a visibly ailing Edhi expressed a wish to see a political revolution in Pakistan. When pressed for details, he prophesied a Khomeni-like savior. “When conditions deteriorate to such an extent,” he said in his frail, phlegmy voice, “such men become inevitable. They may be late, but they are inevitable.”

Alas, such men and their predictably self-righteous and often misplaced passions pale in comparison to the transparent services of one Abdul Sattar Edhi, a man whose wilful residence on the margins of society offers the only template for Pakistan’s salvation – and that is the truest (and oldest) form of democracy.

The main gate for the rulers, the “other” gates for commoners. Business as usual in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, where doors are always being opened for the high and mighty.

But it is a testament to Abdul Sattar Edhi’s greatness, and to the tragedy of the country he leaves behind, that on the day of his funeral, Pakistan’s credibility-hungry generals and politicians were lining up behind his coffin to bask in some reflected glory.

Who was Abdul Sattar Edhi? A conventional timeline places him in a strife-ridden century: born in 1928 in what is now Indian Gujarat, this young Bantva Memon was deeply affected by his mother’s physical paralysis, and tended to her until her death when he was 19. After Partition, Edhi moved to Karachi and sold cloth in its wholesale market. But the panoply of afflictions in that migrant-heavy city appealed to his conscience: in the 1950s he set up a drug dispensary, then a makeshift hospital to treat victims of an influenza epidemic, then an ambulance service for the victims of the 1965 war with India. In the last thirty years of his life, as Karachi was wracked by ethnic and sectarian violence, Edhi’s duty-bound ambulances could be seen beeping from site to site, their red-and-white logo a hope-instilling icon of commitment and consistency.

For such a motivated man, Edhi was remarkably free of ambition. In fact it would be accurate to say that his life was one long exercise in self-abnegation. Famously “simple” and unfussy, Edhi sat on a wooden bench in his office, slept in a windowless room and drew no salary from his sprawling network of charities. He is said to have owned only two pairs of clothes when he died. In these Tolstoyan attempts at transparency and moral exactitude, this perpetually perturbed-looking, white-bearded nana (as he was called by the children in his orphanage) was steadfastly assisted by his wife Bilquis, who came to embody the virtues of patience and forbearance, the necessary sabr to his saadgi.

The accounts of acquaintances and journalists all conjure up a clear-eyed man, one who had no time for abstract or overly romantic ideas about poverty. “Never give to beggars,” he once told a wealthy philanthropist from Lahore. Another time, recalling the plight of people wounded in the 1965 war, he admitted, “My heart became so hard after that. I made humanity my religion and devoted my life to it.”

In the 1990s, he was approached by General Hameed Gul and Imran Khan for mercenary enlistment against Benazir Bhutto’s government. But Edhi refused to redeem their conspiracy with his participation, even when they threatened him with force. “They wanted to fire a gun from my shoulder,” he told an interviewer, “but I wouldn’t let them.”

How might we assess the legacy of such a Spartan and singularly upright figure? First, by placing him in a long line of revolutionary ascetics, men whose renunciation of wealth and power bestowed on them a purifying aura of spiritual and moral authority. The Buddha, the Sufis, even Gandhi with his complicated engagement of colonial power, all rose to prominence through a paradoxical shunning of privilege; it was their symbolic embrace of poverty that became their capital, their nearness to suffering that elevated them in the eyes of a cynical and motive-wary public. For Abdul Sattar Edhi, who lived in a particularly turbulent time, and who witnessed first hand the toxicification of Pakistan’s religious fabric, that passage to sainthood was lined with the additional pitfall of the new-age missionary’s deceptive piety. Let us not forget that Edhi was operating his orphanages and soup kitchens in the age of Jamaat-ud-Dawa and other insidious “charities” whose bright and shiny aid programs are often fronts for hate-filled recruitment drives. Indeed, let us uphold Edhi’s stance on religious discrimination as reformist and exemplary: “There were many who asked me, ‘Why must you pick up Christians and Hindus in your ambulance?’ And I said, ‘Because the ambulance is more Muslim than you.’”

In one of his last interviews, a visibly ailing Edhi expressed a wish to see a political revolution in Pakistan. When pressed for details, he prophesied a Khomeni-like savior. “When conditions deteriorate to such an extent,” he said in his frail, phlegmy voice, “such men become inevitable. They may be late, but they are inevitable.”

Alas, such men and their predictably self-righteous and often misplaced passions pale in comparison to the transparent services of one Abdul Sattar Edhi, a man whose wilful residence on the margins of society offers the only template for Pakistan’s salvation – and that is the truest (and oldest) form of democracy.