The imminent retirement—as of now—of Chief of Army Staff General Raheel Sharif continues to attract speculation. The rumour mill and alarmist analysts are still talking about whether the general will bow out quietly or pursue some misadventure to trump the civilian Sharif. None of this gossip was quelled by his announcement early this year that he would not be seeking an extension. Those who speculate about the November decision dredge up history, citing the peculiar past of the Pakistan army when it comes to such matters. Perhaps they should give more weight to the immediate past.

Pakistan’s army, the bedrock of an otherwise fragile state, may not be the most progressive of institutions. But recent developments suggest that our military leaders realise it needs to change, even if key concerns remain, said the Guardian in 2010, months after General Ashfaq Kayani had replaced General Musharraf as the chief of army staff.

Unlike his predecessor, Kayani came across as a modest man of a few words, focused on military matters, even if the army stood out as the predominant stakeholder in domestic politics. He generally avoided “rhetorical flourishes or getting involved in public politics.”

Kayani had inherited an army that reeled from the long controversial Musharraf years. His primary focus was to rehabilitate its image, contain and neutralize the bloody spate of violence and acknowledge the rank and file. Never before had a COAS focused so much energy on the welfare of the soldier as much as Kayani did. He dealt with possibly the worst multiple security crises this country ever faced, particularly the years 2009 to 2011. Despite that, recalls General Asif Yasin, a former corps commander, Gen. Kayani spent four Eids in various Fata forward locations. He even raised money—at least $300 million—for the flood-affected Swat following his meeting with an Abu Dhabi prince.

General Sharif, too, commands respect as much as Kayani did, but there is one slight difference: Raheel Sharif doesn’t hold back when he deems it fit to express his reservations on issues that he holds dear. The National Action Plan (NAP), the Karachi operation or the anti-corruption campaign are three cases in point. He stirred the political nest by expressing his displeasure over NAP in November last year as well as on August 13, both during corps commander conferences. Some of his passion with the anti-terror and anti-corruption projects resonated in his September 6 speech a little over a week ago at the General Headquarters too.

The content of the speech simply reaffirmed the military’s concerns about the government’s performance in dealing with the problems already identified, such as the future of the anti-terror Protection of Pakistan Act that expired in July, the poor prosecution of cases, the lack of progress on the Federally Administered Tribal Areas and madressah reform. There have been problems raising the new Frontier Corps wings in Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and a lack of focus on capacity building of civilian law-enforcement agencies.

Describing the National Action Plan as central to the consolidation of gains from Operation Zarb-i-Azb, Gen. Raheel once again pointed out that unless all arms deliver meaningfully and all inadequacies are addressed, remnants of terrorism would continue to simmer and long-term peace and stability would remain a distant dream. Similarly, under Gen. Raheel, the army establishment began openly naming India for the troubles in Balochistan and elsewhere. This too has been seen as displeasing for the prime minister.

His candid opinions on major components of NAP have been as discomforting for the civilian government as have been his foreign visits, particularly those to Saudi Arabia and the extended one to the US in 2015. Most civilian politicians simply overlook or perhaps advertently ignore the fact that, regardless of who the COAS is, the bulk of foreign tours take place on invitations to the chief by his counterparts abroad.

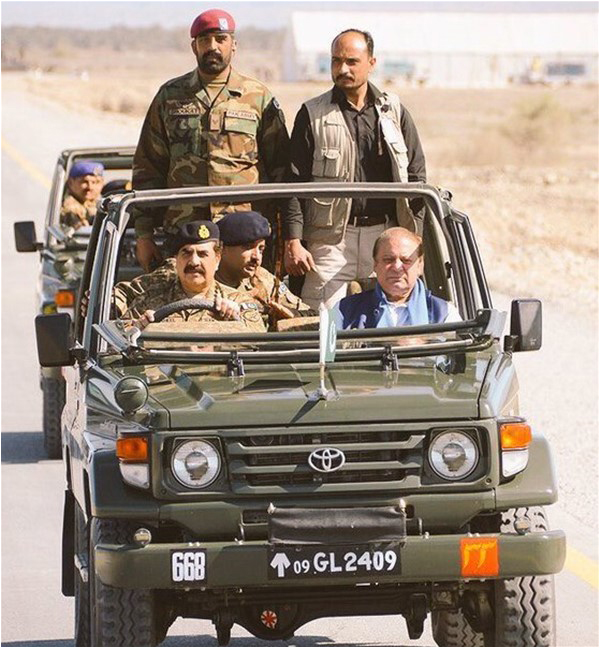

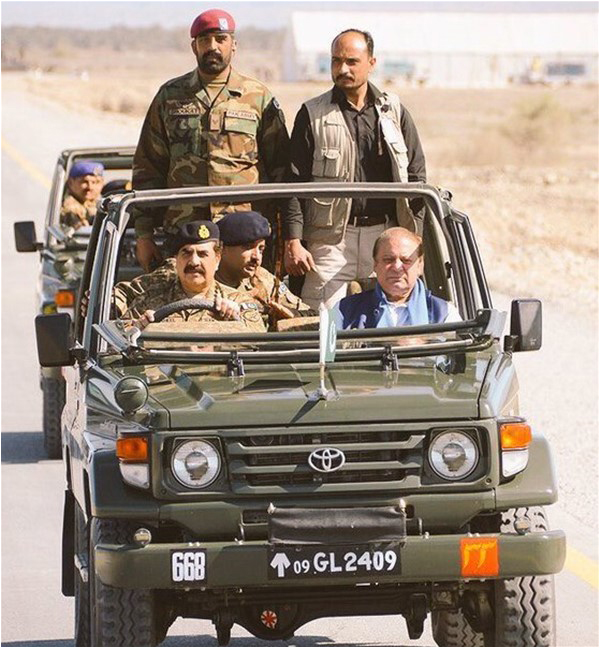

Zarb-i-Azb, his personal engagement and the response to the attack on the Army Public School have all counted as the omni presence of the COAS. Add to this his endless morale-boosting interaction with his soldiers from the north to the south and it is not difficult to see why this has won him praise and recognition as a professional soldier. Much of his efforts are buttressed by the massive public relations campaign by the ISPR which has mastered the art of strategic communications. In contrast, most of the PML-N brigade, led by a visibly unhealthy prime minister, has been seen as preoccupied with Imran Khan. The military machinery, all the while, churns ahead with a focus on how to highlight the role it plays in Pakistan. The big ticket in this campaign, of course, remains the chief of army staff, largely to the displeasure of the civilian authorities. His performance as an army chief is being interpreted, in a smug circularity of logic, as reason or argument enough for him to want an extension. These quarters seem to suggest that if someone does a good job, they would want to continue in the post.

Those who have been busy talking about Gen. Raheel’s career, and entertaining rumours of an extension, might consider that their entire debate has been coloured by a subtext of the civil-military tensions. A more pertinent question, rather than whether Gen. Raheel will stay or go, is if the civilians are ready to recalibrate their conduct in governance if they want to trump the military apparatus. As long as the civilians are unwilling to stick their necks out in national interest, the civil-military balance will remain skewed. In essence, whether the next COAS is Gen. Raheel or someone else, the government should know that it has to perform regardless.

Imtiaz Gul heads the independent Centre for Research and Security Studies in Islamabad

Pakistan’s army, the bedrock of an otherwise fragile state, may not be the most progressive of institutions. But recent developments suggest that our military leaders realise it needs to change, even if key concerns remain, said the Guardian in 2010, months after General Ashfaq Kayani had replaced General Musharraf as the chief of army staff.

Unlike his predecessor, Kayani came across as a modest man of a few words, focused on military matters, even if the army stood out as the predominant stakeholder in domestic politics. He generally avoided “rhetorical flourishes or getting involved in public politics.”

Most of the PML-N brigade, led by a visibly unhealthy prime minister, has been seen as preoccupied with Imran Khan. The military machinery, all the while, churns ahead with a focus on how to highlight the role it plays in Pakistan

Kayani had inherited an army that reeled from the long controversial Musharraf years. His primary focus was to rehabilitate its image, contain and neutralize the bloody spate of violence and acknowledge the rank and file. Never before had a COAS focused so much energy on the welfare of the soldier as much as Kayani did. He dealt with possibly the worst multiple security crises this country ever faced, particularly the years 2009 to 2011. Despite that, recalls General Asif Yasin, a former corps commander, Gen. Kayani spent four Eids in various Fata forward locations. He even raised money—at least $300 million—for the flood-affected Swat following his meeting with an Abu Dhabi prince.

General Sharif, too, commands respect as much as Kayani did, but there is one slight difference: Raheel Sharif doesn’t hold back when he deems it fit to express his reservations on issues that he holds dear. The National Action Plan (NAP), the Karachi operation or the anti-corruption campaign are three cases in point. He stirred the political nest by expressing his displeasure over NAP in November last year as well as on August 13, both during corps commander conferences. Some of his passion with the anti-terror and anti-corruption projects resonated in his September 6 speech a little over a week ago at the General Headquarters too.

The content of the speech simply reaffirmed the military’s concerns about the government’s performance in dealing with the problems already identified, such as the future of the anti-terror Protection of Pakistan Act that expired in July, the poor prosecution of cases, the lack of progress on the Federally Administered Tribal Areas and madressah reform. There have been problems raising the new Frontier Corps wings in Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and a lack of focus on capacity building of civilian law-enforcement agencies.

Describing the National Action Plan as central to the consolidation of gains from Operation Zarb-i-Azb, Gen. Raheel once again pointed out that unless all arms deliver meaningfully and all inadequacies are addressed, remnants of terrorism would continue to simmer and long-term peace and stability would remain a distant dream. Similarly, under Gen. Raheel, the army establishment began openly naming India for the troubles in Balochistan and elsewhere. This too has been seen as displeasing for the prime minister.

His candid opinions on major components of NAP have been as discomforting for the civilian government as have been his foreign visits, particularly those to Saudi Arabia and the extended one to the US in 2015. Most civilian politicians simply overlook or perhaps advertently ignore the fact that, regardless of who the COAS is, the bulk of foreign tours take place on invitations to the chief by his counterparts abroad.

Zarb-i-Azb, his personal engagement and the response to the attack on the Army Public School have all counted as the omni presence of the COAS. Add to this his endless morale-boosting interaction with his soldiers from the north to the south and it is not difficult to see why this has won him praise and recognition as a professional soldier. Much of his efforts are buttressed by the massive public relations campaign by the ISPR which has mastered the art of strategic communications. In contrast, most of the PML-N brigade, led by a visibly unhealthy prime minister, has been seen as preoccupied with Imran Khan. The military machinery, all the while, churns ahead with a focus on how to highlight the role it plays in Pakistan. The big ticket in this campaign, of course, remains the chief of army staff, largely to the displeasure of the civilian authorities. His performance as an army chief is being interpreted, in a smug circularity of logic, as reason or argument enough for him to want an extension. These quarters seem to suggest that if someone does a good job, they would want to continue in the post.

Those who have been busy talking about Gen. Raheel’s career, and entertaining rumours of an extension, might consider that their entire debate has been coloured by a subtext of the civil-military tensions. A more pertinent question, rather than whether Gen. Raheel will stay or go, is if the civilians are ready to recalibrate their conduct in governance if they want to trump the military apparatus. As long as the civilians are unwilling to stick their necks out in national interest, the civil-military balance will remain skewed. In essence, whether the next COAS is Gen. Raheel or someone else, the government should know that it has to perform regardless.

Imtiaz Gul heads the independent Centre for Research and Security Studies in Islamabad