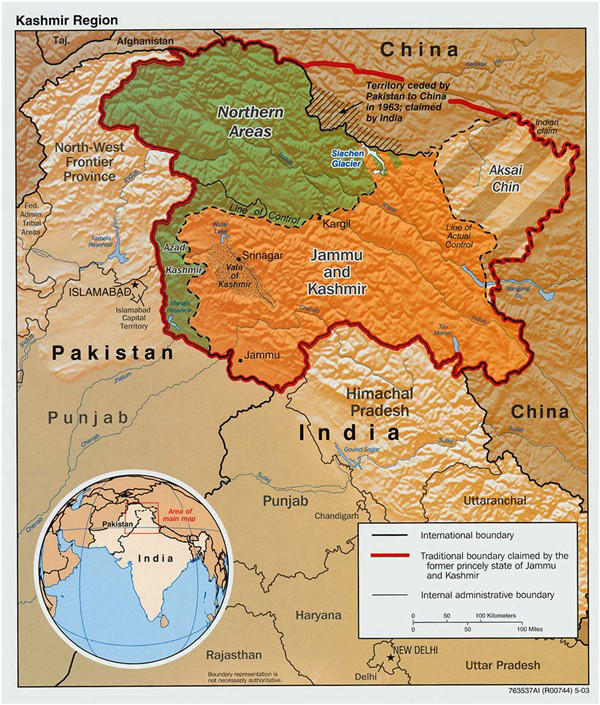

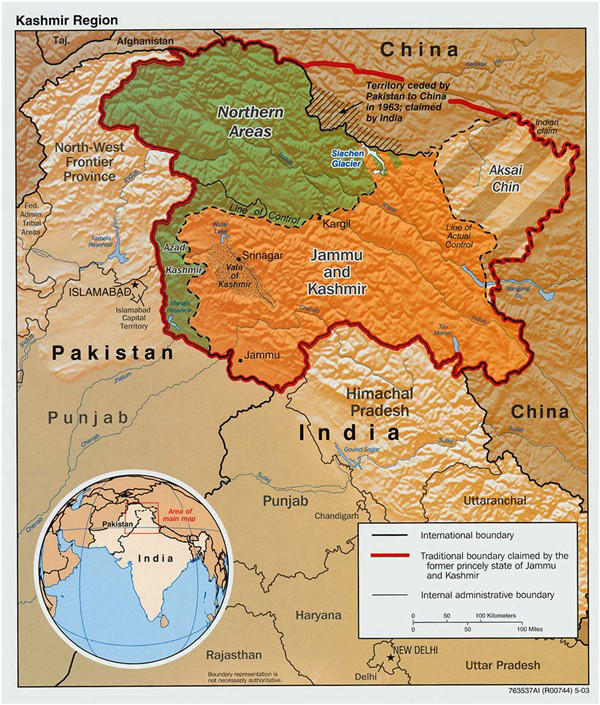

Kashmir has been a bone of contention between Pakistan and India since the two nations parted ways in 1947. Following Partition, both countries exercised their claim over the former independent princely state, leading to the establishment of the Line of Control (LoC), dividing Kashmir between India and Pakistan after a UN-backed ceasefire. However, that did not resolve the issue and there have been occasional skirmishes in the region every few years. The violence reached its peak during the 1980s and 1990s, claiming thousands of lives and leading to grave human rights violations. Mattters appeared to settle down in the early 2000s as both sides showed increased faith in the dialogue process (according to figures by the South Asia Terrorism Portal, the number of casualties went down from 4,507 in 2001 to 377 in 2009), also leading to the 1999 Lahore Declaration, in which both India and Pakistan committed to the peaceful resolution of the Kashmir issue.

Since 2010, sporadic instances of violence have triggered tension and loss of numerous civilian lives. The most recent episode took place after Indian security forces gunned down Hizbul Mujahideen commander Burhan Muzaffar Wani, who was considered a freedom fighter by some and a separatist militant by others, on July 8. His death sparked a series of protests and led to at least 60 deaths in the clashes that ensued between civilians and Indian security forces. The use of pellet guns by Indian security forces to disperse protests also led to the “dead eyes” epidemic, which caused mutilated retinas, severed optic nerves and irises seeping out for the victims.

Pakistan categorized Wani’s death as an extra-judicial killing and Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif wrote a letter to the United Nations secretary-general two weeks ago, urging him to send a fact-finding mission to Indian-Administered Jammu & Kashmir to investigate the violations of international humanitarian law being perpetrated by the Indian security forces. The secretary-general, in response, offered to play the role of the mediator between Pakistan and India, but according to Pakistan’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations, Maleeha Lodhi, any mediatory role can be played if both parties come to the table. “India continues to harp on the theme that it is an internal matter for India and there is nothing to talk about,” she told The Friday Times. “And a series of offers made by Pakistan to talk about the Kashmir issue have been spurned.”

Lodhi maintains that India’s unwillingness to either accept bilateral talks or to accept some kind of a multilateral role has been the main roadblock in the resolution of the Kashmir issue. She adds that Pakistan has always focused on both aspects of the issue – human rights violations and self-determination for Kashmiris, as there is a cause and effect role between the two. Munir Akram, Pakistan’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations from 2002 to 2008, agrees with Lodhi’s position. According to Akram, India will only come to the negotiating table once it is compelled to do so by losing control on the ground, which is not the case right now as India is operating from a position of strength.

However, according to political analyst Shuja Nawaz, when Pakistan and India talk about Kashmir, they tend to forget the crux of the issue—the Kashmiris themselves. “I think the conflict can only be resolved by the people of the region,” Nawaz said, adding that there was a new demographic of Kashmiri youth taking the reins in the region, whose voices can no longer be ignored. “What Pakistan can do is not be seen as an active participant in fueling insurgence in the area, provide moral support to people from the area to raise their own voice and try and set Azad Kashmir as an example of how a democratic, autonomous region can operate.”

Despite the long-drawn out nature and gravity of the conflict, the Kashmir issue has received limited attention on global platforms. Lodhi says the OIC and a few other countries have backed Pakistan’s position but the issue ultimately falls victim to power politics. “International focus is divided between various issues and the amount of attention a certain issue gets from big powers is really contingent on their interest—at the end of the day principle is trounced by interest,” she says. Akram adds that in the current global environment, unfortunately Muslim struggles are equated with terrorist struggles. “The success of a Muslim group over a non-Muslim one is seen as a triumph for militants,” he says. While he recognizes the presence of militant elements in the regions, he emphasizes that it is unfair to lump legitimate struggles, such as the ones in Kashmir and Palestine, with the illegitimate ones. Nawaz, however, feels that for the international community to pay attention, it is important for local, credible and recognizable voices from Kashmir to take global stage, instead of the issue being tossed back and forth between Pakistan and India, which ultimately ends up looking like a blame game. On the other hand, Michael Kugelman, senior program associate for South Asia at the Woodrow Wilson International Center, feels that it is wise of the international community not to try to mediate the dispute, as India might reject external involvement, arguing that the status of the region has long been settled. In fact, he suggests an alternative approach of the two sides engaging in confidence-building measures, such as initiating talks on trade, education, water sharing, and so forth, that build up repositories of goodwill and allow them to tackle the “tough stuff like Kashmir.”

Both Lodhi and Akram fear that the Kashmir situation has the potential to escalate into very dangerous tensions between Pakistan and India and constitutes a great security threat in the region. Lodhi says Pakistan’s position has always been consistent i.e. that there is no military solution to the problem, the LOC cannot be the basis of a solution as it divides the Kashmiri people and it is critical to involve the Kashmiris in the ultimate evolution of a situation. But the gridlock cannot end unless India meets them halfway. However, not everyone is equally optimistic. Kugelman considers Kashmir one of those perpetually hyper-intractable disputes, similar to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, in which no matter how much progress you may make, you always end up falling short. “The question, ultimately, is if India and Pakistan can find ways to somehow get along even if you continue to have the status quo in Kashmir—a status that is precarious and explosive, based on what we’re seeing on the ground there these days. In other words, can India and Pakistan move beyond Kashmir?”

Sarah Munir is a freelance journalist based in New York

Note: This story had incorrectly spelled Maliha. It has since been amended.

Since 2010, sporadic instances of violence have triggered tension and loss of numerous civilian lives. The most recent episode took place after Indian security forces gunned down Hizbul Mujahideen commander Burhan Muzaffar Wani, who was considered a freedom fighter by some and a separatist militant by others, on July 8. His death sparked a series of protests and led to at least 60 deaths in the clashes that ensued between civilians and Indian security forces. The use of pellet guns by Indian security forces to disperse protests also led to the “dead eyes” epidemic, which caused mutilated retinas, severed optic nerves and irises seeping out for the victims.

Pakistan categorized Wani’s death as an extra-judicial killing and Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif wrote a letter to the United Nations secretary-general two weeks ago, urging him to send a fact-finding mission to Indian-Administered Jammu & Kashmir to investigate the violations of international humanitarian law being perpetrated by the Indian security forces. The secretary-general, in response, offered to play the role of the mediator between Pakistan and India, but according to Pakistan’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations, Maleeha Lodhi, any mediatory role can be played if both parties come to the table. “India continues to harp on the theme that it is an internal matter for India and there is nothing to talk about,” she told The Friday Times. “And a series of offers made by Pakistan to talk about the Kashmir issue have been spurned.”

Lodhi maintains that India’s unwillingness to either accept bilateral talks or to accept some kind of a multilateral role has been the main roadblock in the resolution of the Kashmir issue. She adds that Pakistan has always focused on both aspects of the issue – human rights violations and self-determination for Kashmiris, as there is a cause and effect role between the two. Munir Akram, Pakistan’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations from 2002 to 2008, agrees with Lodhi’s position. According to Akram, India will only come to the negotiating table once it is compelled to do so by losing control on the ground, which is not the case right now as India is operating from a position of strength.

However, according to political analyst Shuja Nawaz, when Pakistan and India talk about Kashmir, they tend to forget the crux of the issue—the Kashmiris themselves. “I think the conflict can only be resolved by the people of the region,” Nawaz said, adding that there was a new demographic of Kashmiri youth taking the reins in the region, whose voices can no longer be ignored. “What Pakistan can do is not be seen as an active participant in fueling insurgence in the area, provide moral support to people from the area to raise their own voice and try and set Azad Kashmir as an example of how a democratic, autonomous region can operate.”

Despite the long-drawn out nature and gravity of the conflict, the Kashmir issue has received limited attention on global platforms. Lodhi says the OIC and a few other countries have backed Pakistan’s position but the issue ultimately falls victim to power politics. “International focus is divided between various issues and the amount of attention a certain issue gets from big powers is really contingent on their interest—at the end of the day principle is trounced by interest,” she says. Akram adds that in the current global environment, unfortunately Muslim struggles are equated with terrorist struggles. “The success of a Muslim group over a non-Muslim one is seen as a triumph for militants,” he says. While he recognizes the presence of militant elements in the regions, he emphasizes that it is unfair to lump legitimate struggles, such as the ones in Kashmir and Palestine, with the illegitimate ones. Nawaz, however, feels that for the international community to pay attention, it is important for local, credible and recognizable voices from Kashmir to take global stage, instead of the issue being tossed back and forth between Pakistan and India, which ultimately ends up looking like a blame game. On the other hand, Michael Kugelman, senior program associate for South Asia at the Woodrow Wilson International Center, feels that it is wise of the international community not to try to mediate the dispute, as India might reject external involvement, arguing that the status of the region has long been settled. In fact, he suggests an alternative approach of the two sides engaging in confidence-building measures, such as initiating talks on trade, education, water sharing, and so forth, that build up repositories of goodwill and allow them to tackle the “tough stuff like Kashmir.”

Both Lodhi and Akram fear that the Kashmir situation has the potential to escalate into very dangerous tensions between Pakistan and India and constitutes a great security threat in the region. Lodhi says Pakistan’s position has always been consistent i.e. that there is no military solution to the problem, the LOC cannot be the basis of a solution as it divides the Kashmiri people and it is critical to involve the Kashmiris in the ultimate evolution of a situation. But the gridlock cannot end unless India meets them halfway. However, not everyone is equally optimistic. Kugelman considers Kashmir one of those perpetually hyper-intractable disputes, similar to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, in which no matter how much progress you may make, you always end up falling short. “The question, ultimately, is if India and Pakistan can find ways to somehow get along even if you continue to have the status quo in Kashmir—a status that is precarious and explosive, based on what we’re seeing on the ground there these days. In other words, can India and Pakistan move beyond Kashmir?”

Sarah Munir is a freelance journalist based in New York

Note: This story had incorrectly spelled Maliha. It has since been amended.