"I have to go to a meeting, I'm getting late." These words, seemingly ordinary, were the final echoes of an extraordinary life. Karamat Ali, a man who had lived 78 years with the intensity of a thousand suns, uttered them as he prepared to embark on his final journey.

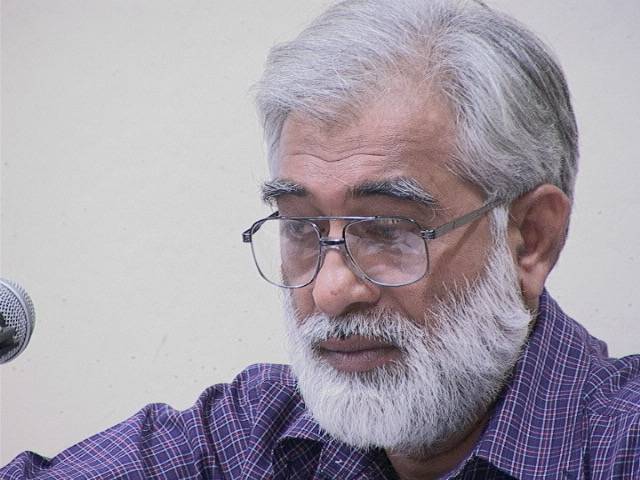

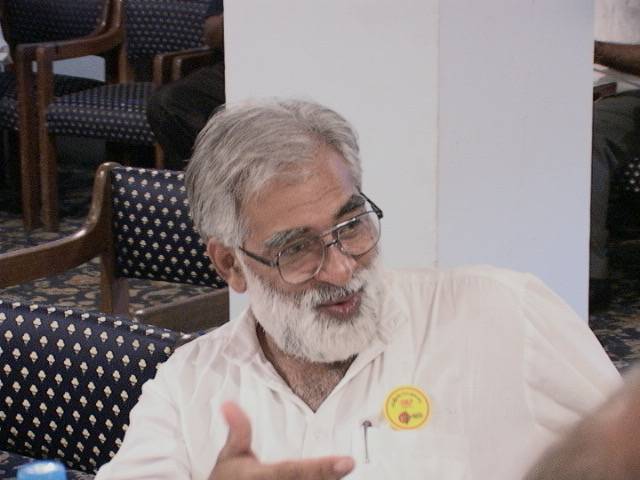

Picture a man with eyes that sparkled with wisdom, framed by a halo of white hair. Karamat was no ordinary soul; he was a living, breathing archive of human struggle and resilience. His mind, a vast library of labour laws, political histories, and the vibrant tapestry of seven decades of social change, never ceased to whir with activity.

Even as dementia clouded his final days, Karamat's spirit remained undiminished. In the sterile confines of Aga Khan Hospital's isolation ward, his eyes seemed to gaze into a realm beyond the present. Here was a man who had never known stillness, who had filled every moment with purpose - speaking, organising, striking, protesting. Now, in this unexpected quiet, the film reel of his remarkable life played on in his mind.

But to truly understand Karamat, we must journey back to the dusty streets of Multan, where a young boy's heart first flickered with the flame of rebellion. It was a solemn procession, with the air heavy with mourning. Among the devout, a child's voice rings out, clear and defiant. Young Karamat, facing his Shia father, declares he will no longer participate in self-flagellation during these rituals. "Until the wealthy join us in our pain," he proclaims, "we will not bear it alone."

Karamat's courageous stand became the cornerstone of a philosophy that prioritised human dignity and social justice over blind adherence to religious customs. This early act of defiance set the stage for a life dedicated to challenging not just religious norms, but any system that perpetuated inequality or oppression. Karamat's path was set - he would become a beacon for those who dared to question, to challenge, to fight for justice.

Fast forward to Emerson College, where the simple act of ringing a school bell became a clarion call for change. In a tense situation, exiled students from Karachi during Ayub’s era, seeking refuge from oppression, find an unexpected ally in Karamat. At the gates of Multan College, there stood Mukhtar Rizvi, Meraj Muhammad Khan, and Nafees Siddiqui – not just men, but living embodiments of resistance and hope. With no prior experience in activism, Karamat listens to their plight and asks a simple question: "How can I help?" The answer – a strike – leads to a clash that would open Karamat's eyes to the power of collective action.

Young Karamat, facing his Shia father, declares he will no longer participate in self-flagellation during these rituals. "Until the wealthy join us in our pain," he proclaims, "we will not bear it alone"

In that moment, as students faced off against the police, a revelation dawned. Karamat realised that even in the face of military rule, the united voice of students could shake the foundations of power. It was a lesson he would carry with him, a torch he would bear proudly for the rest of his days.

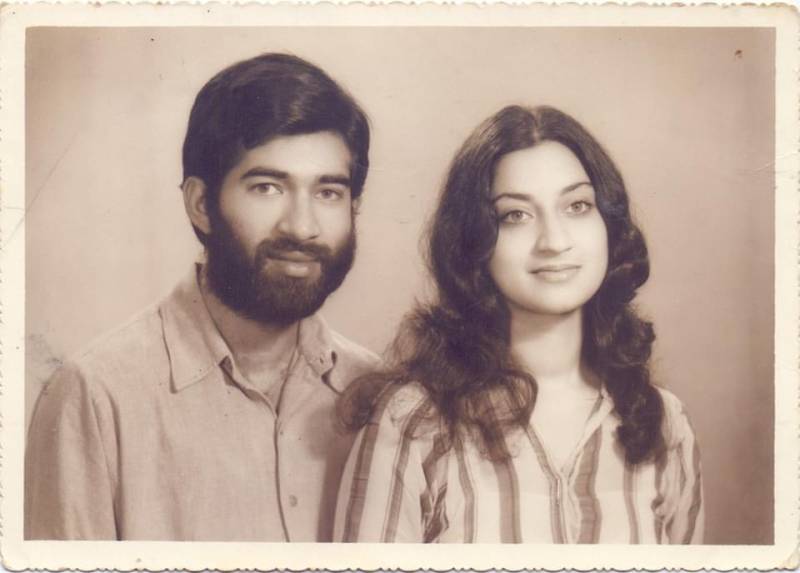

Looking back, in the vibrant city of Karachi, a young man from Multan arrived with dreams in his eyes and determination in his heart. Karamat Ali, like countless others, juggled college studies with factory work, his struggles mirroring those of his mother back home, where she worked in a textile factory Gul Textile Mill. In the threads of their shared sacrifice, a legacy of resilience was woven, each stitch a step towards a brighter future.

Little did Karamat know that fate had cast him for a greater role in the theatre of social change. One fateful day in the 1960s, he arrived at the factory gates to find not just closed doors, but the awakening of a movement. Thousands of workers, united in purpose, marched on the streets of Karachi. In that heated moment, Karamat's individual journey merged with the collective struggle, igniting a lifelong passion to be a part of labour union.

In the tumultuous 1970s, not just in Pakistan but globally, the political landscape was undergoing profound changes. Resistance movements, student politics, and waves of labour revolutions were sweeping through Karachi, a city that had become a crucible of activism. This decade witnessed an extraordinary labour movement that stood firm against Ayub Khan's dictatorship, shaking the foundations of capitalist tranquillity. It was during this fervent time that Karamat Ali, riding Wakeel Khan Swati's motorcycle and Usman Baloch's Vespa, would incite factory workers in industrial zones to rise in revolt. The crescendo of this rebellion was a citywide shutdown of Karachi for three days, a testament to the workers' relentless demand for their rights, with Karamat and Usman Baloch at the very heart of this uprising.

Karamat Ali's foray into Karachi's progressive student politics was an audacious move, undertaken without any prior connections or endorsements. According to Basir Naveed, the leadership of the National Student Federation (NSF) initially hesitated to embrace him. Yet, Karamat's adeptness in dialogue and his fearless demeanour soon made him an indispensable force in student politics. The students affiliated with Jamiat, lacking in the art of discourse, wielded sticks against their adversaries. In the face of these brutal attacks, Karamat often emerged bloodied but unbowed. Mehnaz Rahman vividly recalls a harrowing incident during an NSF protest against Ayub Khan. As she witnessed Karamat being violently beaten by Jamiat students, she screamed in terror when one of the attackers picked up a cement block, poised to strike Karamat's head. Her scream, a cry of sheer desperation, startled the assailants, causing them to flee.

Karamat was, indeed, a figure of remarkable versatility. While the labour movement defined much of his struggle, his universal persona embraced a myriad of roles. He was deeply involved in progressive politics, peace efforts, and support for oppressed classes. His contributions spanned journalism, economics, resistance literature, and the arts, painting a portrait of a man whose life was a testament to unyielding commitment and multifaceted brilliance. Karamat's legacy is a vivid narrative of courage, resilience, and an unwavering quest for justice in a world rife with challenges.

In the heart of Karachi stood the Pakistan Institute of Labour Education and Research (PILER) Centre, a beacon of hope and learning for the working class. This building was more than just a structure; it was a university for workers, a sanctuary where long speeches by trade union leaders echoed through its halls, and collective chants of solidarity resonated within its walls. For over forty years, this centre became the nucleus that kept thousands of workers connected, imparting political and resistance training to those who walked through its doors.

From the coal mines of Balochistan to the match factories of Charsadda, from the beeri worker unions of Larkana to the voices of the fishermen of Ibrahim Hyderi, labourers from all corners of Pakistan converged at PILER. It was here that labour leaders from across South Asia, including prominent figures from India, gathered, hosted by Karamat Ali, to dream of global worker unity. Visionaries like Tapen Bhose and Comrade Usman Baloch joined forces, singing songs of peace and solidarity.

I remember seeing delegations of Indian journalists at the PILER Centre, their Karachi tour led by Jatin Desai and journalists from the Bombay Press Club. Their experiences translated into newspapers filled with messages of peace. In every speech, Karamat passionately opposed the war frenzy and arms race between Pakistan and India. His dedication to peace extended beyond borders; he became part of an international campaign against weapons, uniting regional leaders through the student unions of Oxford and Cambridge Universities in England. He resonated with peace-loving Indians, agreeing that the battle for peace must be fought on their lands.

Upon returning to Pakistan, Karamat established forums like the Peace Coalition and the Pakistan-India Peace Forum, spearheading long marches for peace between the two countries. Our friend Aslam Khawaja even embarked on a journey from Delhi to Karachi on foot. Caravans of hundreds crossed the Wagah border, symbolising unity, sometimes from one side, sometimes the other. In 2004, during the World Social Forum in Bombay, Pakistani comrades filled trains bound for India, embodying the spirit of cross-border solidarity. PILER was at the heart of this human movement, hosting peace activists like Dr Sandeep Pandey, Didi Nirmala Deshpande, and Kuldip Nayar, who tirelessly advocated for peace on both sides of the border.

Little did Karamat know that fate had cast him for a greater role in the theatre of social change. One fateful day in the 1960s, he arrived at the factory gates to find not just closed doors, but the awakening of a movement

The PILER Centre transformed into an international political meeting place, a hub where peace activists, progressive leaders, and revolutionary workers from around the globe spent days and nights weaving dreams of change. It was a place where hope was nurtured, and the seeds of a better future were sown, one filled with unity, peace, and unwavering solidarity.

Karamat and BM Kutty's partnership wove a tapestry of influence that stretched across the political landscapes of both India and Pakistan, guiding their leaders like beads strung together on a rosary. The doors of PILER (Pakistan Institute of Labour Education and Research) were always open to the top brass from India's Communist parties and Congress's Gandhi leadership, with their visits becoming a familiar and constant presence. Among them was Didi Nirmala Deshpande, a towering figure in the Indian Congress Party, who brought an entire delegation of Congress leaders to Pakistan, bearing a message of goodwill for earthquake victims. Karamat, ever the gracious host, accompanied Didi Nirmala Deshpande throughout Sindh. Such was their bond that Didi requested Karamat to immerse a portion of her ashes in the sacred waters of the Indus River after her death. In a gesture that transcended borders and historical animosities, a Pakistan Air Force plane carried Sherry Rehman, BM Kutty, and Karamat to Delhi for her funeral. Karamat, with a reverence befitting their friendship, wrapped her ashes in a handkerchief and took them to Shah Latif's shrine before finally immersing them in the Indus River in Sukkur.

PILER Centre was a hub for Pakistani politicians, particularly the leadership of Balochistan, who seemed to be permanent guests of Karamat and Kutty. Three generations of Ghous Bakhsh Bizenjo's family maintained close ties with Karamat. BM Kutty's typewriter might well have drafted the most resolutions for Pakistan's leftist politics, and Karamat's magnetic charisma drew pro-democracy factions and political discussions like a beacon. Rasool Bux Palijo was one of Karamat's closest friends. After negotiating with Zia-ul-Haq, it was Karamat who secured Palijo's release from Lahore jail and arranged for his treatment in England. Palijo acknowledged that his international leftist connections were largely thanks to Karamat.

Karamat's deep care for his comrades was legendary. When Ghous Bakhsh Bizenjo battled cancer, Karamat stayed in England, looking after him, handling everything from laundry to grooming. He also supported the struggling Anila Naz, who was fighting cancer while advocating for the Anjuman Mazarain. Karamat provided her with shelter at PILER, taking care of her food, drink, and medical treatment for an entire year. Anila Naz wept more than Karamat's own children at his funeral, a testament to his profound impact on her life.

In the heart of Karachi stood the Pakistan Institute of Labour Education and Research (PILER) Centre, a beacon of hope and learning for the working class. This building was more than just a structure; it was a university for workers

Umar Asghar Khan spent his last evening at PILER. Karamat, struck by grief, was silent for days following Umar Asghar's death. At Umar's memorial, Karamat revealed that when Umar left the army to start teaching in Lahore, he dedicated half his salary to support worker education and training at PILER. The silent tears of Asghar Khan and Umar Asghar's wife at PILER spoke volumes of their shared sorrow.

Lal Khan and Chaudhry Manzoor regularly organised ideological education sessions for comrades at PILER, benefiting from Karamat's generosity and vast network. Karamat never kept his connections to himself; instead, he shared them freely, touring the country with his guests, ensuring they experienced the breadth and depth of Pakistan's struggles and hopes.

According to Sheema Kermani, Karamat was the epitome of a complete Marxist. Living humbly in a two-room house in Gulshan-e-Memar, he never sought the luxuries of Karachi's posh areas, steadfastly maintaining his middle-class identity and welcoming people from all walks of life into his world. The hostel rooms at Pakistan Institute of Labour Education and Research (PILER) were a testament to this inclusivity, hosting everyone from factory workers to government ministers. There, revolutionary and pro-democracy advocates alike enjoyed simple meals of lentils and rice, lovingly prepared by Inam Bengali and Roshan Thari.

Karamat was a remarkable orator. The stage never intimidated him; he would often sit quietly in the back rows without an invitation, yet inevitably, the stage would call him forth. Such was the magnetic pull of his presence. He dined with drivers, even in five-star hotels, and stood in solidarity with the downtrodden during their protests. His humility and courage knew no bounds.

Throughout his life, Karamat was a tireless champion for the oppressed. Whether seeking compensation for the burned workers of the Baldia factory or advocating for bonded labourers, Karamat showed up everywhere, fully prepared and organised. He knocked on the doors of the Supreme Court and navigated international organisations with equal finesse. His relentless advocacy made him a full-time lawyer for the marginalised, always ready to fight their battles.

Karamat's friendships were vast and diverse. He was a lifetime member of the Arts Council and a familiar face at the Karachi Press Club gallery, with a network of friends that spanned every corner of society. Even in his final year, while resting on a bed at the National Institute of Cardiovascular Diseases (NICVD), he was still connected to his passions, listening to Mukesh's songs. Despite the doctors' efforts to treat his illness, Karamat maintained his unique habit of mixing alcohol with mineral water, even on his sickbed.

One memorable incident showcased his unyielding spirit. During a rally against the US invasion of Iraq at Mazar-e-Quaid, Karamat, feeling the heat, shared his drink with Muhammad Hussain Mehnati, Karachi's leader of Jamaat-e-Islami. Mehnati, after taking a sip, curiously asked what Karamat had mixed into the water. With a twinkle in his eye, Karamat smiled and replied, "You've tasted a heavenly drink while still alive."

Karamat Ali's sense of humour was as sharp as his political acumen. Evening sessions at PILER were often punctuated with bouts of laughter as Karamat and BM Kutty exchanged jokes, lightening the weight of their heavy discussions. Karamat once recounted a story of how he had told prominent communists of the time that the dinner for that night included wild boar hunted by Mir Ali Ahmed Khan Talpur. This revelation caused quite a stir among the staunch comrades, who ended up vomiting in reaction. Such tales highlighted Karamat's exceptional wit and his ability to find humour even in the most serious of situations.

But Karamat was much more than a source of laughter; he was an international leader of immense repute. His personal friends included luminaries like Nobel Peace Prize winner Desmond Tutu and former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan. He counted Palestinian fighter Leila Khaled among his friends and hosted Kashmiri separatist leader Yasin Malik in Karachi for three days. During the 2006 World Social Forum in Karachi, even the Dalai Lama was expected to attend, underscoring the global significance of Karamat's network. Activists like Arundhati Roy and Medha Patkar were part of his circle, and from Iqbal Ahmed Khan to Tariq Ali, hundreds of international intellectuals were connected with him. Economists from across Pakistan, including Ghulam Kibriya, Akbar Zaidi, Qaiser Bengali, Asad Sayeed, and Dr Aly Ercelawn, frequented PILER, discussing and advocating for workers' rights.

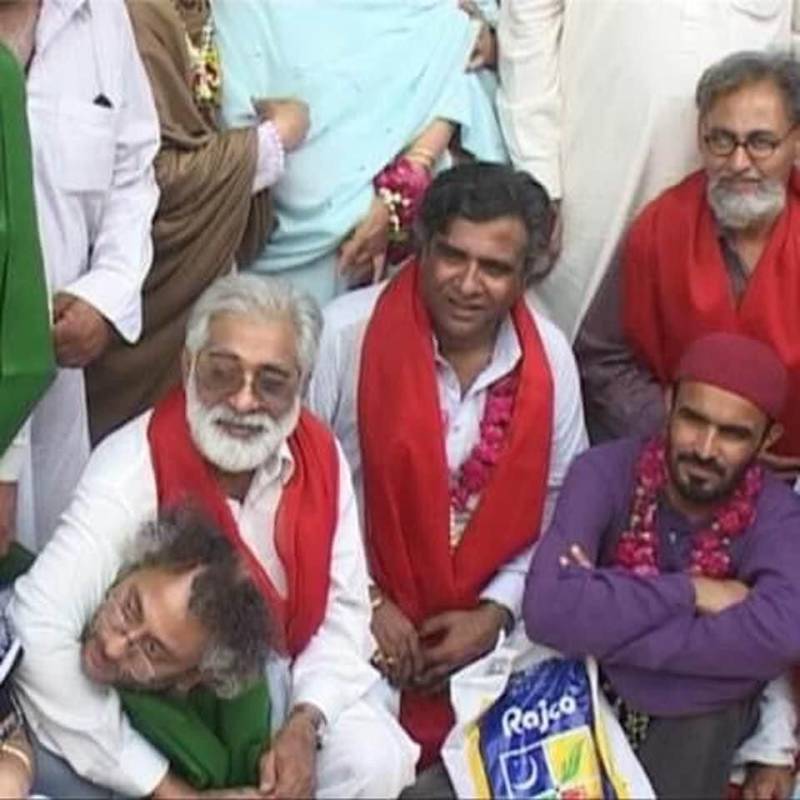

Karamat believed that progressives were in the minority and thus needed to unite despite their differences to raise a collective voice. His ability to bring people together was part of his charm. He succeeded in uniting all factions of trade unions on a single stage, and I personally witnessed gatherings of Sindh's nationalist leaders at the PILER Centre. There wasn't a single progressive, democratic, or peace-loving gathering in Karachi that Karamat wasn't a part of. His remarkable talent for finding common ground amidst differences made him a unifying force in a fragmented world.

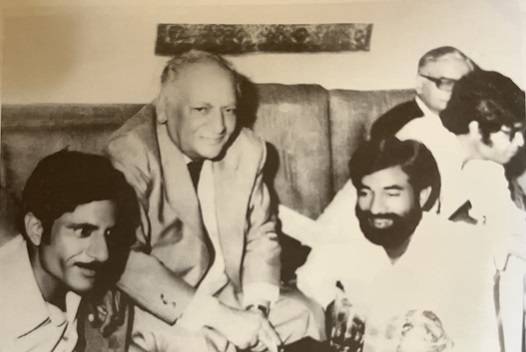

Although Karamat Ali did not align with Zulfikar Bhutto's politics, he maintained close ties with Bhutto's party members, demonstrating his ability to find common ground and build bridges even with those he disagreed with. Karamat often said that Bhutto was not corrupt, a testament to his nuanced understanding of political figures. Benazir Bhutto, Bhutto's daughter, was a personal friend of both Karamat and BM Kutty. When Wali Khan gave an interview to an American journalist, published in Foreign Economic Review, where he lied against Bhutto, Benazir sent a message to Kutty, requesting a rejoinder. It was Karamat who convinced Kutty to pen the response, showcasing his persuasive skills and loyalty to his friends.

Karamat's friendship with Hakim Ali Zardari was equally profound. It began when Karamat handed over his presidential chair to Zardari at a Sindhiyani Tehreek conference in Jungshahi, Thatta. This gesture was repaid when Benazir became Prime Minister. At an MRD leaders' meeting in Karachi, Zardari, holding Karamat by the arm at the gate, said, "My daughter-in-law is now the Prime Minister. Tell me what you need." Such moments highlighted the deep, personal connections Karamat cultivated throughout his life.

Karamat was a master orator. His speeches, delivered with perfect vocal and expressive harmony, often included sharp critiques of the military. For his May Day addresses, Karamat would sit in the library, meticulously taking notes to ensure his messages were both powerful and precise. He often remarked that since the 1970s, workers' issues had remained largely the same, with the only change being the increasing numbers of workers each year.

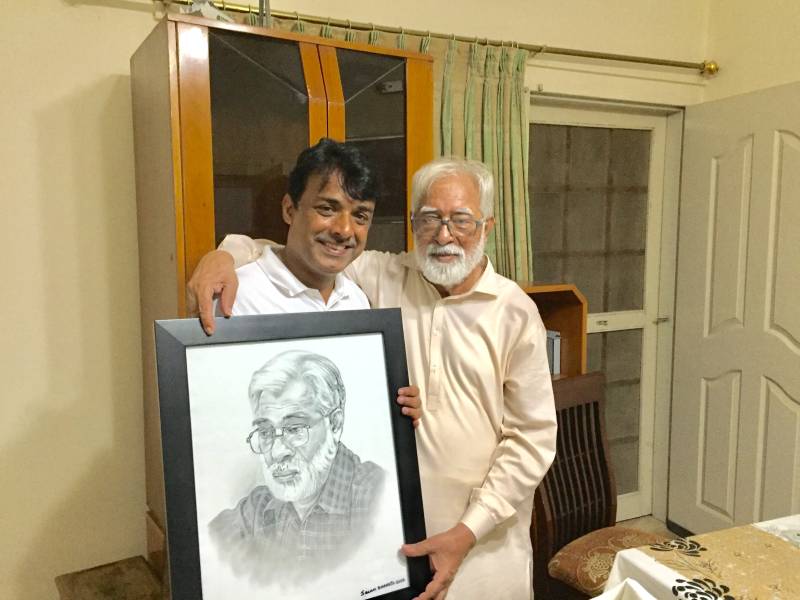

In the Umar Asghar Hall at PILER, there is a gallery of photos of Pakistan's labour leaders, all of whom have passed away. Now, it seems, the last photo in that gallery might be Karamat's. As Sheema Kermani aptly put it, "Karamat was not someone who would sit quietly. Now he has joined his old comrades, probably waking them up for meetings as well."

Karamat's life was a testament to his unyielding commitment to justice, his ability to forge lasting friendships, and his unwavering dedication to the cause of the oppressed. His legacy continues to inspire, reminding us all of the power of unity, the importance of dialogue, and the enduring strength of a committed heart.