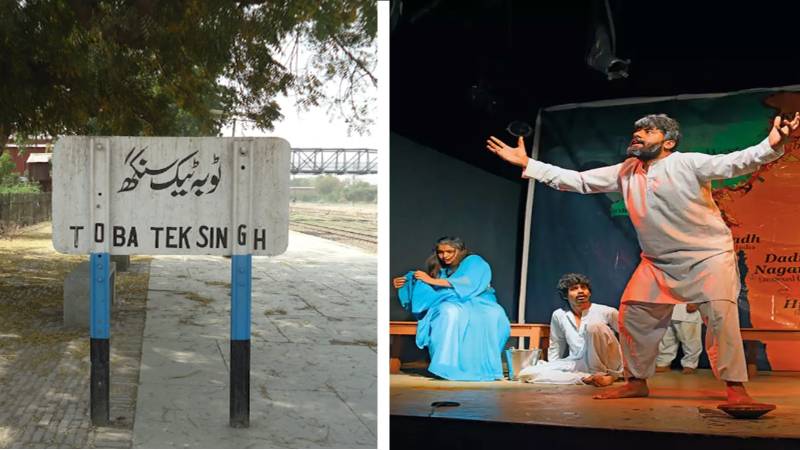

This weekend I reread Saadat Hasan Manto's short story Toba Tek Singh. It reminded me of how powerful a story teller Manto was. Even after 70 years, it remains one of the most memorable Urdu stories. It documents the horrors of the partition of the Punjab, seen through the eyes of the Hindu and Muslim inmates in a lunatic asylum. Suddenly, overnight, they belong neither to Pakistan nor to India.

For many of us who observe the patterns of elections in Pakistan or what is happening in India ,we often wonder: where have we come from and which direction are we heading in? Or, as Bishen Singh so cleverly puts it “uper the gur gur the annex, the bay dhayana, the mung the dal of Pakistan and India…dur fittay moun.”

The lunatics in the asylum of Manto’s story ask rational questions. What is the concept of our land which was once called something else? How can it be called something else with the stroke of a pen? Why do we need to move? What is the purpose of this political upheaval anyway?

Today’s forcibly displaced people, who number over 110 million, may ask themselves the same questions.

Though partition occurred over 70 years ago, the trauma of it still remains – and from it, how do we define ourselves as people?

Growing up, I was quite confused by the notion of being Pakistani. As a child, the concept is hard to grasp – perhaps closely identified with Eid biryanis, comfort food of dal and rice and the road trips along the GT Road. I was seven when we moved abroad, right after Bhutto’s hanging in 1979, and then, returning every year since, the concept has become even more confusing. They say the immigrant experience is like that – you assume the country remains static though things and people change, as do cultural and political norms.

The Pakistan of my childhood no longer exists. It is like being Alice in Wonderland – a disorienting experience where we are in a strange new world, where the rules have changed. Though the surroundings are familiar, the political discourse is not, and it can be a disorienting experience.

No fear of that confusion these days, though, with our political leaders. They are in a political roundabout with the same cast of characters forming and reforming alliances and political affiliations. The French have a saying for this – “plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose” (the more things change, the more they remain the same).

In one of his nine letters written to Chacha Sam, Manto predicted: “We will have buses fitted with American tools. We will have Islamic pajamas stitched by American machines. We will have clods of earth ‘untouched by hands’ from the American soil. We will have American folding stands for the Holy Quran and American prayer-mats.”

He had foreseen the importance of the US to Pakistan even then. Apart from the longstanding ties between the military industry complex in both countries, the US still remains the largest export market for Pakistan, over US$8 billion in 2022, a high source of remittances, over US$3 billion, and a key source of foreign direct investment. Other regional benefactors are not far behind, extracting economic value while building infrastructure, roads, highways and hospitals.

Even with the backdrop of our political instability, we continue to be a resilient nation – recovering whether from earthquakes or floods or the incarceration of our political leaders (a rite of passage). We are now 250-million-strong, lurching in every direction.

Why is stability so important? After all, we have managed so far without it for almost the entirety of Pakistan’s existence.

Stability means having a steady and reliable source of income, a stable home environment, and good health for most people. That is usually what people desire on a daily basis. Political stability, like in relationships or in careers, is almost like having solid ground under our feet. Without it, we teeter and cannot plan for the future. At a national level, it is a regarded as a crucial element which helps to stabilise the various components of our system – whether it be the government, economic or political policies or the efficient functioning of many core facets of our lives, such education, health or even wellbeing.

I stay well away from political armchair analysis, but studying Pakistan’s development data over the last two decades has made me fearful of change and its impact on the youth of our country, and how lack of foresight or future planning makes us vulnerable to more political chaos and a directionless future.

Where is the North Star to guide us into the rest of the 21st century? As I read and watch the unfolding political spectacle, especially after the recent general elections, I am reminded of Manto's reluctant hero Bishen Singh, who shrugs his shoulders and then observes philosophically:

“uper the gur gur the annex the bay dhayana the dal of the Government of Pakistan.”

Sometimes wisdom comes not only from the mouth of babes, but out of the confusion of the divided deranged.