The Lal Masjid (Red Mosque) siege followed in the wake of a series of radical activist campaigns initiated by Islamist women of the associated madrasa of the Jamia Hafsa, and effectively ruptured the façade of the extremist discourse as a purely masculine purview. The government-appointed head cleric (khateeb) of the Lal Masjid, Abdul Rashid Ghazi, was a vocal opponent of joint Pak/US military operations and used the space of the Red Mosque to wage a campaign against them. Two generations of clerics claimed to have enjoyed historical support from members of Pakistan’s intelligence community (Rashid, 2008; Sarwar, 2007).

In 2004, the mosque had issued a fatwa declaring that Pakistani soldiers killed in tribal Waziristan should be denied an Islamic burial, whereas only militants who died in confrontation qualified as ‘martyrs’ for the Islamic cause (Ali, 2014; Munir, 2011; The News, 2013). The effect of such an edict was said to have resulted in refusals by soldiers to enter the battlefield and was later echoed by the amir of the mainstream Islamist party, Jamaat e Islami. In April 2007, the Red Mosque set up its own Sharia courts and warned of thousands of suicide attacks if the government tried to shut these courts down.

The uprising of the Jamia Hafsa women students in Islamabad in 2007 was the only serious political confrontation to General Musharraf ’s dictatorial regime of nine years by any group of women activists. These girl students belonged to a religious school or madrasa, attached to the Lal Masjid in an upscale location in the capital, Islamabad. The women clerics who ran the girls’ madrasa were related to the male imams (clerics) of the main mosque, who in turn were suspected for their affiliation with radical religious militants in the north of the country, in the wake of the war on terror.

In 2007, the young women of the Hafsa madrasa led by Umme Hassan, after a series of vigilante activities in the city, illegally occupied the premises adjoining the mosque land. This was in protest against the government’s threat to demolish and reclaim this property (and other illegally constructed mosques in the city) because it was suspected to have become a hotbed for terrorist indoctrination.

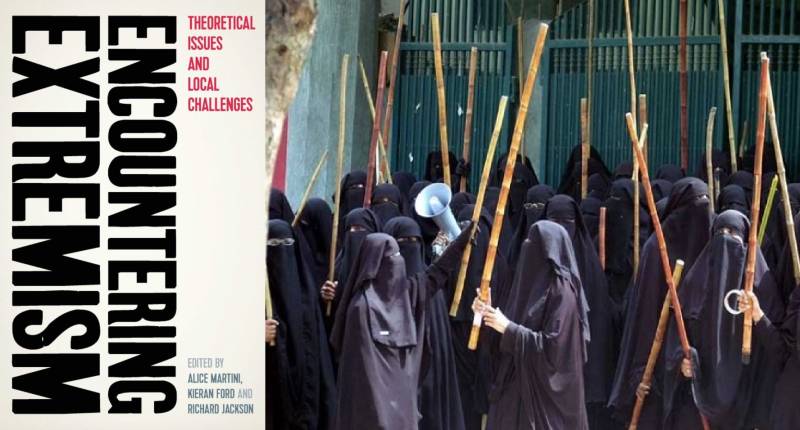

The Jamia Hafsa women wore complete black veils, carried banners in English and Urdu and wore headbands declaring Sharia ya Shahadat (Sharia or martyrdom). They carried bamboo sticks and kidnapped a woman from the neighborhood whom they accused of running a prostitution enterprise. They only let her free once she ‘repented’. The imagery soon caught the attention of global media and challenged the notion of Muslim women as veiled and victimized by oppressive religious practices of their male counterparts and, at times, in need of liberation through military or non-military interventions (Abu-Lughod, 2002; Razack, 2007). This was in diametric opposition to the image of feminine victimhood that the Islamist men were invested in soon after the all-out military operation that followed.

Once negotiations between Musharraf’s government and the Lal Masjid leaders broke down, the state seemed bent on a show of force that resulted in the evacuation of 1,200 occupants, the death of Abdul Rashid Ghazi and an estimated 100–200 fatalities (Bokhari and Johnson, 2007). The spectacle of Maulana Aziz escaping the smoke-filled complex of the Lal Masjid under the disguise of a burqa earned him the mocking and emasculating title of ‘Mulla Burqa’ by critics. After the siege was over, breaking the vow that it was un-Islamic to be photographed, Aziz went on to invoke the victim card and castigate the government in the media and in sermons (Dawn, 2014). He remains a cleric at the reconstructed Lal Masjid at a new site in Islamabad and continues to call for a caliphate to be established in Pakistan.

Umme Hassan too, appeared in the media and justified the kidnapping of Shamim Akhtar by saying ‘She was a factory of Aids and if we got her brothel closed, what is wrong about it?’ (Ansari, 2007). Hassan referred to the government as a ‘lazy mother’ who is neglectful of her duties and claimed that the girls of Jamia Hafsa were only carrying out the government’s job in cleaning up the brothels since the police were unable to crack down on prostitution without retaliation from influential government officials who themselves patronised these brothels (Perlez, 2007). The Jamia Hafsa women claim several of their female students were killed, although the state denies this and there has been no evidence or legal testimony confirming this assertion. The army’s willingness to bomb a site of worship became proof of the state’s brutality and its anti-Islam orientation. For years following, Umme Hassan and her students continued to narrate graphic stories about the atmosphere of death and destruction inside the mosque during Operation Silence. Many have appeared on television to mobilise sympathy and support through their stories of grief. This strategy of ‘truth-telling’ and invocation of gendered tropes to counter the official state narrative surrounding the operation has been immensely successful (Yusuf, 2011).

The state used the uprising to justify the need for more operations against deep-seated terrorist infiltration, and the Islamists marketed it as confirmation that Musharraf’s regime was acting as proxy for anti-Islamic, US governmental interests. The narrative of the survivors reminisced the sufferings of Kashmiri women in a land occupied by non-Muslim infidels and mimicked the Shia tradition of enacting public lamentations during the Islamic month of Muharram to commemorate the historic cruelties suffered by the martyrs of Karbala.

In a booklet entitled Saniha Lal Masjid: Hum Par Kya Guzri that was later published by the mosque administration, Umme Hassan narrates the horrors of the siege and cites last wills posted by the residents on the inside walls and pillars of the mosque as the young women allegedly prepared themselves for the possibility of ‘martyrdom’. The two strongest emotions invoked in such narrations are of grief and forfeiture of feminine desires for the larger political cause. A strategic difference between this and the other women’s religious movements lies in how they appropriate and deploy constructs of ‘woman-as-nation’ in their political activism (Yuval Davis, 1997).

The most pious movement of the Al-Huda in Pakistan emphasizes religious education so that women can raise pious children and families and build more Islamically aligned nations (Ahmad, 2009). For mothers of the militant group Lashkar-e-Tayyaba, their cause is the willingness to sacrifice their sons to become martyrs for the movement and Islamic nation (Haq, 2007). However, the state’s perceived willingness to compromise sovereignty to infidels’ interests motivates the women of Jamia Hafsa to break out of the private, domestic and protective sphere, discard their invisibility and engage in an aggressive moral-cleansing campaign in order to re-build an Islamic nation-state themselves.

Liberal commentators disparagingly viewed these ‘ninjas’, ‘burqa brigades’ and ‘chicks with sticks’ (Shamsie, 2007) as mere pawns in the hands of the Red Mosque’s male leadership, citing their impoverished class backgrounds as the reason behind their susceptibility to manipulation by a powerful leadership seeking a popular base. On the other hand, sympathetic scholars (Bano, 2012) sanitised the politics of the Lal Masjid by denying its historical role with state-sponsored jihadist strategies (Ahmed, 2016; Hussain, 2013) and glorifying the social significance that the women disciples of the Jamia Hafsa derive in their roles as mothers, sisters, wives and daughters, as they spread their Islamic learnings. Bano (2012, p. 146) argues madrasa education and learned piety ‘empower[s] the girls to deal with material scarcity’ and cope with peer pressure against observing Valentine’s Day and fashion trends. Such scholars advocate support for Islamic female leadership as a viable alternative to Western feminism. Some even described the Jamia Hafsa vigilantism as a civil society movement (Devji, 2008, p. 21).

The important point here is that agentive embodied performances are not always docile. This form of ‘agency’ relies on self-construction as authentic moral actors who oppose a supposedly secular state beholden to foreign interests. The cultural purity claimed by the Jamia Hafsa women is invested in rigidly patriarchal constructions of gender and sexuality. Their narrative supports the discipline and purpose of gendered bodies and prescribes their roles and representations in public spaces. The common charge against Islamic militants is that they simply deny women’s agency. This was progressively challenged as militants recognised the potential in offering women temporal roles in the insurgency and immortality as martyrs.

Disclaimer: The above extract is from the chapter authored by Afiya Shehrbano Zia in the book Encountering Extremism; Theoretical Issues and Local Challenges, edited by Alice Martini, Kieran Ford and Richard Jackson, and published by Manchester University Press in 2020.

In 2004, the mosque had issued a fatwa declaring that Pakistani soldiers killed in tribal Waziristan should be denied an Islamic burial, whereas only militants who died in confrontation qualified as ‘martyrs’ for the Islamic cause (Ali, 2014; Munir, 2011; The News, 2013). The effect of such an edict was said to have resulted in refusals by soldiers to enter the battlefield and was later echoed by the amir of the mainstream Islamist party, Jamaat e Islami. In April 2007, the Red Mosque set up its own Sharia courts and warned of thousands of suicide attacks if the government tried to shut these courts down.

The uprising of the Jamia Hafsa women students in Islamabad in 2007 was the only serious political confrontation to General Musharraf ’s dictatorial regime of nine years by any group of women activists. These girl students belonged to a religious school or madrasa, attached to the Lal Masjid in an upscale location in the capital, Islamabad. The women clerics who ran the girls’ madrasa were related to the male imams (clerics) of the main mosque, who in turn were suspected for their affiliation with radical religious militants in the north of the country, in the wake of the war on terror.

In 2007, the young women of the Hafsa madrasa led by Umme Hassan, after a series of vigilante activities in the city, illegally occupied the premises adjoining the mosque land. This was in protest against the government’s threat to demolish and reclaim this property (and other illegally constructed mosques in the city) because it was suspected to have become a hotbed for terrorist indoctrination.

The Jamia Hafsa women wore complete black veils, carried banners in English and Urdu and wore headbands declaring Sharia ya Shahadat (Sharia or martyrdom). They carried bamboo sticks and kidnapped a woman from the neighborhood whom they accused of running a prostitution enterprise. They only let her free once she ‘repented’. The imagery soon caught the attention of global media and challenged the notion of Muslim women as veiled and victimized by oppressive religious practices of their male counterparts and, at times, in need of liberation through military or non-military interventions (Abu-Lughod, 2002; Razack, 2007). This was in diametric opposition to the image of feminine victimhood that the Islamist men were invested in soon after the all-out military operation that followed.

Once negotiations between Musharraf’s government and the Lal Masjid leaders broke down, the state seemed bent on a show of force that resulted in the evacuation of 1,200 occupants, the death of Abdul Rashid Ghazi and an estimated 100–200 fatalities (Bokhari and Johnson, 2007). The spectacle of Maulana Aziz escaping the smoke-filled complex of the Lal Masjid under the disguise of a burqa earned him the mocking and emasculating title of ‘Mulla Burqa’ by critics. After the siege was over, breaking the vow that it was un-Islamic to be photographed, Aziz went on to invoke the victim card and castigate the government in the media and in sermons (Dawn, 2014). He remains a cleric at the reconstructed Lal Masjid at a new site in Islamabad and continues to call for a caliphate to be established in Pakistan.

Umme Hassan too, appeared in the media and justified the kidnapping of Shamim Akhtar by saying ‘She was a factory of Aids and if we got her brothel closed, what is wrong about it?’ (Ansari, 2007). Hassan referred to the government as a ‘lazy mother’ who is neglectful of her duties and claimed that the girls of Jamia Hafsa were only carrying out the government’s job in cleaning up the brothels since the police were unable to crack down on prostitution without retaliation from influential government officials who themselves patronised these brothels (Perlez, 2007). The Jamia Hafsa women claim several of their female students were killed, although the state denies this and there has been no evidence or legal testimony confirming this assertion. The army’s willingness to bomb a site of worship became proof of the state’s brutality and its anti-Islam orientation. For years following, Umme Hassan and her students continued to narrate graphic stories about the atmosphere of death and destruction inside the mosque during Operation Silence. Many have appeared on television to mobilise sympathy and support through their stories of grief. This strategy of ‘truth-telling’ and invocation of gendered tropes to counter the official state narrative surrounding the operation has been immensely successful (Yusuf, 2011).

The state used the uprising to justify the need for more operations against deep-seated terrorist infiltration, and the Islamists marketed it as confirmation that Musharraf’s regime was acting as proxy for anti-Islamic, US governmental interests. The narrative of the survivors reminisced the sufferings of Kashmiri women in a land occupied by non-Muslim infidels and mimicked the Shia tradition of enacting public lamentations during the Islamic month of Muharram to commemorate the historic cruelties suffered by the martyrs of Karbala.

In a booklet entitled Saniha Lal Masjid: Hum Par Kya Guzri that was later published by the mosque administration, Umme Hassan narrates the horrors of the siege and cites last wills posted by the residents on the inside walls and pillars of the mosque as the young women allegedly prepared themselves for the possibility of ‘martyrdom’. The two strongest emotions invoked in such narrations are of grief and forfeiture of feminine desires for the larger political cause. A strategic difference between this and the other women’s religious movements lies in how they appropriate and deploy constructs of ‘woman-as-nation’ in their political activism (Yuval Davis, 1997).

The most pious movement of the Al-Huda in Pakistan emphasizes religious education so that women can raise pious children and families and build more Islamically aligned nations (Ahmad, 2009). For mothers of the militant group Lashkar-e-Tayyaba, their cause is the willingness to sacrifice their sons to become martyrs for the movement and Islamic nation (Haq, 2007). However, the state’s perceived willingness to compromise sovereignty to infidels’ interests motivates the women of Jamia Hafsa to break out of the private, domestic and protective sphere, discard their invisibility and engage in an aggressive moral-cleansing campaign in order to re-build an Islamic nation-state themselves.

Liberal commentators disparagingly viewed these ‘ninjas’, ‘burqa brigades’ and ‘chicks with sticks’ (Shamsie, 2007) as mere pawns in the hands of the Red Mosque’s male leadership, citing their impoverished class backgrounds as the reason behind their susceptibility to manipulation by a powerful leadership seeking a popular base. On the other hand, sympathetic scholars (Bano, 2012) sanitised the politics of the Lal Masjid by denying its historical role with state-sponsored jihadist strategies (Ahmed, 2016; Hussain, 2013) and glorifying the social significance that the women disciples of the Jamia Hafsa derive in their roles as mothers, sisters, wives and daughters, as they spread their Islamic learnings. Bano (2012, p. 146) argues madrasa education and learned piety ‘empower[s] the girls to deal with material scarcity’ and cope with peer pressure against observing Valentine’s Day and fashion trends. Such scholars advocate support for Islamic female leadership as a viable alternative to Western feminism. Some even described the Jamia Hafsa vigilantism as a civil society movement (Devji, 2008, p. 21).

The important point here is that agentive embodied performances are not always docile. This form of ‘agency’ relies on self-construction as authentic moral actors who oppose a supposedly secular state beholden to foreign interests. The cultural purity claimed by the Jamia Hafsa women is invested in rigidly patriarchal constructions of gender and sexuality. Their narrative supports the discipline and purpose of gendered bodies and prescribes their roles and representations in public spaces. The common charge against Islamic militants is that they simply deny women’s agency. This was progressively challenged as militants recognised the potential in offering women temporal roles in the insurgency and immortality as martyrs.

Disclaimer: The above extract is from the chapter authored by Afiya Shehrbano Zia in the book Encountering Extremism; Theoretical Issues and Local Challenges, edited by Alice Martini, Kieran Ford and Richard Jackson, and published by Manchester University Press in 2020.