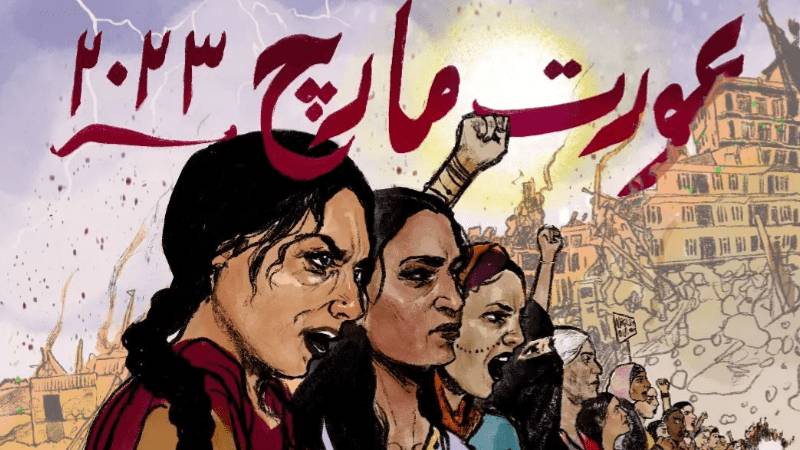

Aurat March 2023 is here, and so is its unabashed opposition and antagonism from the state and sections of society.

Every year close to the International Women’s Day, March 8, there ensues an onslaught of feminists, especially those at the forefront of the Aurat March (AM) organisation. Every year without fail, parts of the mainstream media erupt in frenzy against AM and its allies, while social media explodes with anti-feminist fury.

From 2018 to 2020, AM progressively increased its outreach and media impact, despite a far greater backlash from a wide range of social groups, including opposition from some of the purportedly liberal voices. As the noise increased, so did the diversity of AM participants. Six years on, it is now pertinent to take stock of how the society, state, and feminist collective behind AM have changed. Or not.

In 2018 when the younger generations of Pakistani feminists in Karachi made a move to organise the Aurat March – women’s day rallies as we used to call it in the 1980s and 90s – we were all taken aback by the success – in terms of diversity and volume of participation. The participants revolted against the patriarchal social order and, for the first time, used humour and satire effectively in slogans and speeches.

The system had to respond, and it did. Women were attacked from all fronts – the religious zealots, hyper-nationalists, netizens, and even liberals. For the rest of the month, feminists were made to face ferocious attacks on their integrity by the media and conservative religious quarters. Their agency and motives were questioned, and they were denounced as agents of the West on a mission to destroy the moral order of Islamic Pakistan.

The ripples that AM created in 2018 were enough to shake feminists – or feminist-leaning liberals who weren’t yet ready to be labelled feminists – from slumber. By 2019, there was a visible excitement to make it the next big thing in town and be part of it. And voila – a diverse range of social classes and ideological groups joined the Aurat March in 2019.

That year, women repeated the Mera Jism Meri Marzi slogan in unison after it became the ultimate thorn in the eyes of the religiously inclined, social conservatives, and section of liberal ‘democrats’ alike. The attacks on AM increased manifold.

But that did not deter women from raising it again in 2020. That’s when Khalilur Rehman Qamar made a joke of himself days before the March by melting down using abusive words on live TV – a first in the history of television in Pakistan. The next day, feminist collectives in Lahore, Karachi, Islamabad, Hyderabad, and Quetta raised the slogan in their meetings in an ultimate act of defiance. That year, the Aurat March was joined by Pakistani women in many capitals, including London and Washington D.C., who organised solidarity events on March 8.

If antagonism and attacks on AM were increasing, women’s enthusiasm and rebellious energy were increasing at double the speed. By 2021, however, the backlash had become too strong, dangerous and violent after the Lal Masjid extremists vandalised the AM mural in Islamabad, the March participants were attacked, and the organisers were accused of blasphemy. In 2022, the March was changed to a jalsa in Islamabad with a lesser number of people attending. In almost all the cities that year, the manifestos and slogans of Aurat March and Aurat Azadi March showed a shift from radical dissent to a more accommodating and non-confrontational tone from the organising bodies and participants. The slogans had become far more sanitised, and Islamabad had even retreated on Mera Jism Meri Marzi. The defensive attitude of AM organisers and participants, which was with good reason, was too conspicuous to ignore.

The ‘Rosa Luxemburgism’ of Pakistani feminism that had created the AM fabric is seemingly either losing its ground or is retreating from its original position of forceful rejection of religion-inspired patriarchal values governing women’s bodies. There is, however, still a sliver of the inking of denunciation of the bourgeois standards of morality. It might have been part of strategic expediency in the wake of a violent Islamist backlash, but it has still changed the initial flavour of the resistance. The ideology must find a way to meet the strategy and expediency somewhere midway. Without this, AM would remain short of becoming a movement while being reduced to a project with too many project leaders competing with each other.

Opposition by the state is one of the many challenges that AM faces. Days before the event, the civil administration of at least two cities – Lahore and Islamabad – refused AM the no-objection certificate for holding the event due to ‘security concerns’ and ‘controversial’ placards. This probably alludes to the placards insisting upon the autonomy of women’s bodies and asserting their sexual agency. Not to forget that these were essentially the slogans that Islamabad’s jalsa willingly allowed to forego in 2022 in the hope of greater acceptance from a wider spectrum of society. Some feminists were lamenting that the new feminist movement had pitched itself against religion ‘needlessly’, leaving a vast space for Islamist parties. The 2000-strong Haya March, a counter rally by Jamat-e-Islami women, has been attacking AM for its supposed anti-Islam and anti-culture shades. It is a debate for another day that the party Haya March women belong to does not allow women to be head of the party.

To sum it up, relinquishing the dissent might not be the best strategy to win support or dilute the opposition. That it is counterproductive should be clear from the administration’s denials to hold Aurat March in two big cities. Also, it is important to have an honest debate within the feminist collective on ideological differences to agree on minimum feminist agenda without compromising group-specific values and principles of secularism, democracy, and dissent against patriarchy and imperialism. But far more important is to retain the ability to work together despite the unavoidable competition for attention owing to the new social media order.

With all its strengths and challenges, one thing is clear: Aurat March is here to stay. You may love or hate it but you can’t ignore it.

Every year close to the International Women’s Day, March 8, there ensues an onslaught of feminists, especially those at the forefront of the Aurat March (AM) organisation. Every year without fail, parts of the mainstream media erupt in frenzy against AM and its allies, while social media explodes with anti-feminist fury.

From 2018 to 2020, AM progressively increased its outreach and media impact, despite a far greater backlash from a wide range of social groups, including opposition from some of the purportedly liberal voices. As the noise increased, so did the diversity of AM participants. Six years on, it is now pertinent to take stock of how the society, state, and feminist collective behind AM have changed. Or not.

In 2018 when the younger generations of Pakistani feminists in Karachi made a move to organise the Aurat March – women’s day rallies as we used to call it in the 1980s and 90s – we were all taken aback by the success – in terms of diversity and volume of participation. The participants revolted against the patriarchal social order and, for the first time, used humour and satire effectively in slogans and speeches.

The system had to respond, and it did. Women were attacked from all fronts – the religious zealots, hyper-nationalists, netizens, and even liberals. For the rest of the month, feminists were made to face ferocious attacks on their integrity by the media and conservative religious quarters. Their agency and motives were questioned, and they were denounced as agents of the West on a mission to destroy the moral order of Islamic Pakistan.

The ripples that AM created in 2018 were enough to shake feminists – or feminist-leaning liberals who weren’t yet ready to be labelled feminists – from slumber. By 2019, there was a visible excitement to make it the next big thing in town and be part of it. And voila – a diverse range of social classes and ideological groups joined the Aurat March in 2019.

That year, women repeated the Mera Jism Meri Marzi slogan in unison after it became the ultimate thorn in the eyes of the religiously inclined, social conservatives, and section of liberal ‘democrats’ alike. The attacks on AM increased manifold.

But that did not deter women from raising it again in 2020. That’s when Khalilur Rehman Qamar made a joke of himself days before the March by melting down using abusive words on live TV – a first in the history of television in Pakistan. The next day, feminist collectives in Lahore, Karachi, Islamabad, Hyderabad, and Quetta raised the slogan in their meetings in an ultimate act of defiance. That year, the Aurat March was joined by Pakistani women in many capitals, including London and Washington D.C., who organised solidarity events on March 8.

Relinquishing dissent might not be the best strategy to win support or dilute the opposition. That it is counterproductive should be clear from the administration’s denials to hold Aurat March in two big cities. Also, it is important to have an honest debate within the feminist collective on ideological differences to agree on minimum feminist agenda without compromising group-specific values and principles of secularism, democracy, and dissent against patriarchy and imperialism.

If antagonism and attacks on AM were increasing, women’s enthusiasm and rebellious energy were increasing at double the speed. By 2021, however, the backlash had become too strong, dangerous and violent after the Lal Masjid extremists vandalised the AM mural in Islamabad, the March participants were attacked, and the organisers were accused of blasphemy. In 2022, the March was changed to a jalsa in Islamabad with a lesser number of people attending. In almost all the cities that year, the manifestos and slogans of Aurat March and Aurat Azadi March showed a shift from radical dissent to a more accommodating and non-confrontational tone from the organising bodies and participants. The slogans had become far more sanitised, and Islamabad had even retreated on Mera Jism Meri Marzi. The defensive attitude of AM organisers and participants, which was with good reason, was too conspicuous to ignore.

The ‘Rosa Luxemburgism’ of Pakistani feminism that had created the AM fabric is seemingly either losing its ground or is retreating from its original position of forceful rejection of religion-inspired patriarchal values governing women’s bodies. There is, however, still a sliver of the inking of denunciation of the bourgeois standards of morality. It might have been part of strategic expediency in the wake of a violent Islamist backlash, but it has still changed the initial flavour of the resistance. The ideology must find a way to meet the strategy and expediency somewhere midway. Without this, AM would remain short of becoming a movement while being reduced to a project with too many project leaders competing with each other.

Opposition by the state is one of the many challenges that AM faces. Days before the event, the civil administration of at least two cities – Lahore and Islamabad – refused AM the no-objection certificate for holding the event due to ‘security concerns’ and ‘controversial’ placards. This probably alludes to the placards insisting upon the autonomy of women’s bodies and asserting their sexual agency. Not to forget that these were essentially the slogans that Islamabad’s jalsa willingly allowed to forego in 2022 in the hope of greater acceptance from a wider spectrum of society. Some feminists were lamenting that the new feminist movement had pitched itself against religion ‘needlessly’, leaving a vast space for Islamist parties. The 2000-strong Haya March, a counter rally by Jamat-e-Islami women, has been attacking AM for its supposed anti-Islam and anti-culture shades. It is a debate for another day that the party Haya March women belong to does not allow women to be head of the party.

To sum it up, relinquishing the dissent might not be the best strategy to win support or dilute the opposition. That it is counterproductive should be clear from the administration’s denials to hold Aurat March in two big cities. Also, it is important to have an honest debate within the feminist collective on ideological differences to agree on minimum feminist agenda without compromising group-specific values and principles of secularism, democracy, and dissent against patriarchy and imperialism. But far more important is to retain the ability to work together despite the unavoidable competition for attention owing to the new social media order.

With all its strengths and challenges, one thing is clear: Aurat March is here to stay. You may love or hate it but you can’t ignore it.