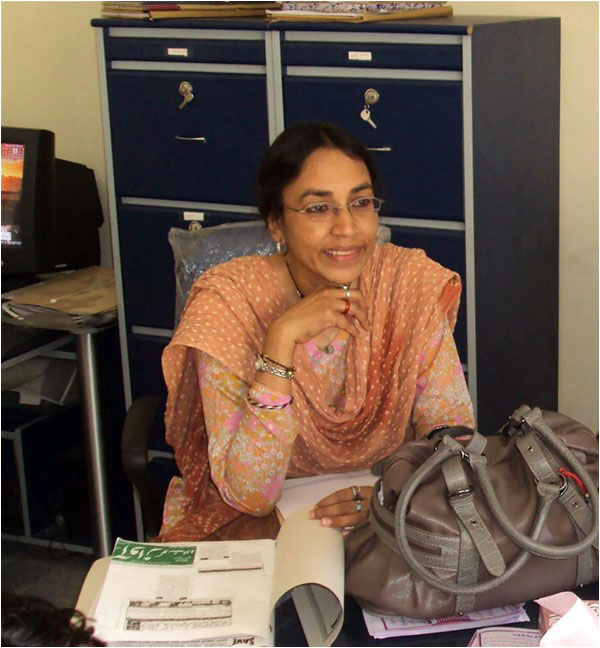

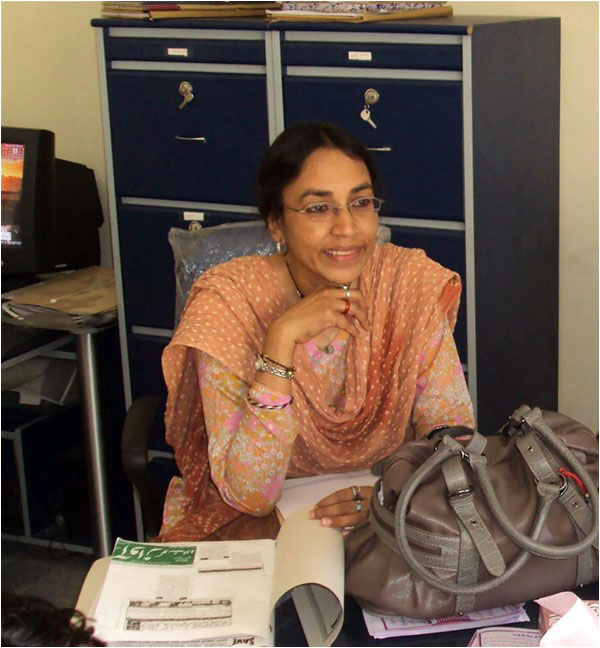

Perween Rahman left us four years ago during the month of March. Countless obituaries and tributes have been paid to the memory of a selfless professional who worked to make the lives of the poor and downtrodden better and respectable. Investigations into her assassination have been through many labyrinths. Many questions still remain unanswered. After her tragic and untimely departure from the development scene in Karachi, many of her close colleagues and fellow comrades have shared their views about her work. A documentary film has also been made on her life and accomplishments to introduce her extraordinary resolve to fight the case of urban poor through solid professional work. However, it is also appropriate to revisit the principles for which Perween stood and refused to compromise on throughout the course of her work at the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP). She taught these principles to her students, co-workers, students and colleagues in many formal and informal discussions.

Perween and her colleagues at OPP considered the underprivileged people a worthy part of society who did not need to live on handouts or charity. Such people, in the absence of state assistance, attempt to change their lives and destiny through self-help. It is in this vein that these communities needed assistance in the form of professional and managerial guidance, Perween believed. They needed support when it came to health care, sanitation, upscaling enterprise, education, building homes and other infrastructure and neighbourhood facilities. In other words, this large population all across Karachi and many other cities and locations in the developing world wanted and needed input from doctors, engineers, educationists, business professionals and architects to develop solutions that they could apply to change their lives. OPP, under the leadership of Perween, had embarked on such a path that aimed to evolve catalytical actions for communities by working closely with them. This appreciation of the plight of the poor was what Perween had the capacity to sharply observe. She had the ability to interact and relate with hard-up people and her intention was to be a catalyst to change through cooperative action. She taught her students of architecture with the same approach.

Her favourite courses were studies in environment and urban planning. Through an informed discussion format, Perween used to lay down key knowledge points around the core topics of the curriculum. She would outline the important facts and observations in her succinct analytical style of review before her students. Then they were asked to add new facts and observations to expand the knowledge base around the subject under discussion. Thus rather dry topics such as the environmental profile of South Asian regions, development and environment interface in Pakistan, a critical review of major human interventions in the natural environment, the reasons for variation in the typologies of buildings and the assessment of diversities in human habitat were deliberated with profound enthusiasm. Perween brought such energy and liveliness to the classroom that even the dull and distracted would find some interesting attribute to be part of the group work. Perween, in her usual unassuming manner and soft voice, would delve into some of the most complicated trajectories of intellectual discourse with effortless ease. Most of the students used to look forward to her class as it provided them the opportunity to freely express and interact with the teacher without any fear of reprimand and rejection. Her simple but bold methodology made many shy and laid-back students gather courage and the strength to speak their minds.

Educational experts are usually of the view that rote learning and textbook-based pedagogy alone cannot sharpen young professionals to address complex challenges in the real world. Perween taught with an objective to make her students observe the ground realities of the topics under discussion. Many such topics were covered by undertaking field observations, surveys and interviews with the area and people concerned. When she was teaching her students the process of evolution of katchi abadis (squatter settlements), she took them to the terrains of Orangi and Qasba to make them observe first-hand the dilapidated and inhuman conditions in which people lived. It was a tough yet life-changing exposure for many architects under training who became motivated to adopt careers for the benefit of the poor and society at large. Perween also emphasized the importance of exploring the real truth behind the obvious situations. Through interviews and other research methods, she taught her students the sequence and process that could lead to the unearthing of reality that was usually hidden under smudgy layers of fiction!

If young people with little or no resources remain unemployed, they can become a huge social liability. Community youth from various underprivileged areas were invited by Perween to learn skills of various kinds to earning a living. She emphasized map-making as a distinct method for projecting analysis and presenting realities. Information gathering around the topic of consideration, basics of drawing, reading and interpreting visual symbols and details, understanding the symbols representing various phenomena and then preparing a commensurate map, accommodating the details, was a usual combination. It may be noted that these young people often had very little backgrounds in formal education. But during their stints of learning at youth training programmes, they not only gained competence as technical expertise but also social entrepreneurship to support themselves. A sizable number of such youth is now gainfully employed in Orangi and elsewhere in Karachi. A small institution, the Technical Training Resource Centre, has been set up by alumni of this programme and is extending valuable services to community members in different regions. Such skilled youth have been instrumental in assisting flood affectees in rebuilding their houses and rehabilitating their enterprises, mapping the unabated land grabbing along the peri-urban village locations in Karachi and extending input to infrastructure development works in under- developed neighbourhoods in various cities. The Asian Coalition for Housing Rights, a large group of development organisations and individuals in this continent, sent many young people from various countries to learn such methodologies from Perween and her comrades. On several occasions, Perween also visited and conducted short trainings in various parts of the world. A sizable number of beneficiaries of such inputs have been all praise for the worthwhile training input and exposure received at her hands. While these professionals did not attain any recognized or high sounding degree, they were called para-professionals, a term coined by OPP to give recognition to this useful cadre of groomed workers.

The best tribute that one can pay Perween is to consolidate the path of training and education of young people around issues of deprived communities. Perween proved, by way of her work and eventually martyrdom, that an alternative path to professional work can lead to a social change, nothing short of a silent revolution!

Perween and her colleagues at OPP considered the underprivileged people a worthy part of society who did not need to live on handouts or charity. Such people, in the absence of state assistance, attempt to change their lives and destiny through self-help. It is in this vein that these communities needed assistance in the form of professional and managerial guidance, Perween believed. They needed support when it came to health care, sanitation, upscaling enterprise, education, building homes and other infrastructure and neighbourhood facilities. In other words, this large population all across Karachi and many other cities and locations in the developing world wanted and needed input from doctors, engineers, educationists, business professionals and architects to develop solutions that they could apply to change their lives. OPP, under the leadership of Perween, had embarked on such a path that aimed to evolve catalytical actions for communities by working closely with them. This appreciation of the plight of the poor was what Perween had the capacity to sharply observe. She had the ability to interact and relate with hard-up people and her intention was to be a catalyst to change through cooperative action. She taught her students of architecture with the same approach.

Perween and her colleagues at OPP considered the underprivileged people a worthy part of society who did not need to live on handouts or charity

Her favourite courses were studies in environment and urban planning. Through an informed discussion format, Perween used to lay down key knowledge points around the core topics of the curriculum. She would outline the important facts and observations in her succinct analytical style of review before her students. Then they were asked to add new facts and observations to expand the knowledge base around the subject under discussion. Thus rather dry topics such as the environmental profile of South Asian regions, development and environment interface in Pakistan, a critical review of major human interventions in the natural environment, the reasons for variation in the typologies of buildings and the assessment of diversities in human habitat were deliberated with profound enthusiasm. Perween brought such energy and liveliness to the classroom that even the dull and distracted would find some interesting attribute to be part of the group work. Perween, in her usual unassuming manner and soft voice, would delve into some of the most complicated trajectories of intellectual discourse with effortless ease. Most of the students used to look forward to her class as it provided them the opportunity to freely express and interact with the teacher without any fear of reprimand and rejection. Her simple but bold methodology made many shy and laid-back students gather courage and the strength to speak their minds.

Community youth from various underprivileged areas were invited by Perween to learn skills of various kinds to earning a living. She emphasized map-making as a distinct method for projecting analysis and presenting realities

Educational experts are usually of the view that rote learning and textbook-based pedagogy alone cannot sharpen young professionals to address complex challenges in the real world. Perween taught with an objective to make her students observe the ground realities of the topics under discussion. Many such topics were covered by undertaking field observations, surveys and interviews with the area and people concerned. When she was teaching her students the process of evolution of katchi abadis (squatter settlements), she took them to the terrains of Orangi and Qasba to make them observe first-hand the dilapidated and inhuman conditions in which people lived. It was a tough yet life-changing exposure for many architects under training who became motivated to adopt careers for the benefit of the poor and society at large. Perween also emphasized the importance of exploring the real truth behind the obvious situations. Through interviews and other research methods, she taught her students the sequence and process that could lead to the unearthing of reality that was usually hidden under smudgy layers of fiction!

If young people with little or no resources remain unemployed, they can become a huge social liability. Community youth from various underprivileged areas were invited by Perween to learn skills of various kinds to earning a living. She emphasized map-making as a distinct method for projecting analysis and presenting realities. Information gathering around the topic of consideration, basics of drawing, reading and interpreting visual symbols and details, understanding the symbols representing various phenomena and then preparing a commensurate map, accommodating the details, was a usual combination. It may be noted that these young people often had very little backgrounds in formal education. But during their stints of learning at youth training programmes, they not only gained competence as technical expertise but also social entrepreneurship to support themselves. A sizable number of such youth is now gainfully employed in Orangi and elsewhere in Karachi. A small institution, the Technical Training Resource Centre, has been set up by alumni of this programme and is extending valuable services to community members in different regions. Such skilled youth have been instrumental in assisting flood affectees in rebuilding their houses and rehabilitating their enterprises, mapping the unabated land grabbing along the peri-urban village locations in Karachi and extending input to infrastructure development works in under- developed neighbourhoods in various cities. The Asian Coalition for Housing Rights, a large group of development organisations and individuals in this continent, sent many young people from various countries to learn such methodologies from Perween and her comrades. On several occasions, Perween also visited and conducted short trainings in various parts of the world. A sizable number of beneficiaries of such inputs have been all praise for the worthwhile training input and exposure received at her hands. While these professionals did not attain any recognized or high sounding degree, they were called para-professionals, a term coined by OPP to give recognition to this useful cadre of groomed workers.

The best tribute that one can pay Perween is to consolidate the path of training and education of young people around issues of deprived communities. Perween proved, by way of her work and eventually martyrdom, that an alternative path to professional work can lead to a social change, nothing short of a silent revolution!