At the end of Thursday’s hearing this week by the House Armed Services Committee examining the U.S. strategy towards ISIS, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs General Martin Dempsey declared, “We’ve got our assets focused like a laser beam on learning more about this enemy.” Amidst all of the logistical and operational talk, it was a refreshing and significant declaration—and an admission that the United States does not know nearly enough.

It is this basic confusion about the nature of ISIS that is putting Washington in danger of failing yet again in the Middle East. The United States seems to have ignored the famous definition of insanity, which is to make the same mistake again and again and hope for a different result. America has within the last few years gone into countries including Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Somalia, and Yemen to fight against Muslim tribal groups. In each case, these societies are currently in chaos and the groups that were the target of the Americans continue to play havoc and spread violence. The new player, which calls itself the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, is yet another example of a tribal group now involved in a direct military confrontation with the United States and its allies.

Events this week pointed up the need to better understand the nature of the enemy if the United States is to win its new war in the Middle East. After Iraqi officials reported that ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi had been wounded in a U.S. airstrike, he apparently emerged in an audio recording Thursday calling for new “volcanoes of jihad” all over the world. A moment of possible triumph appeared to turn into another recruiting opportunity for the jihadists. Another report suggested that ISIS had formed an alliance with a faction of al Qaeda in Syria.

So just who are these people?

Not Getting the Name Right

Obama—and his administration—are not even sure what the name of the enemy is. Obama calls the entity ISIL. His administration talks of ISIS. In one joint news conference, Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel referred to the group as ISIL and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs General Martin Dempsey called it ISIS. Others call it IS or the Islamic State. The group refers to itself as daiish, which is an Arabic acronym for the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria.

The naming of the enemy may be little more than semantics in the course of events of such global import. Yet it is an indication of the confusion that surrounds the subject of ISIS (let us call it that for the purposes of this article—even though POLITICO normally follows the style of the Associated Press, which uses ISIL).

The Scale of the Threat

There is no unanimity on the scale of the threat either. Obama has said that there is no intelligence that is planning any attacks in the United States. ISIS, however, is described in the U.S. media as the greatest threat to the homeland. Senator Lindsey Graham, the Republican from South Carolina, predicted that ISIS would “open the gates of hell” and told Obama to act before “we all get killed back here at home.” Congressmen have actually declared that “ISIS fighters” were caught trying to cross the southern border. Adding to the confusion, the Department of Homeland Security denied that this had occurred.

An “Existentialist Enemy”?

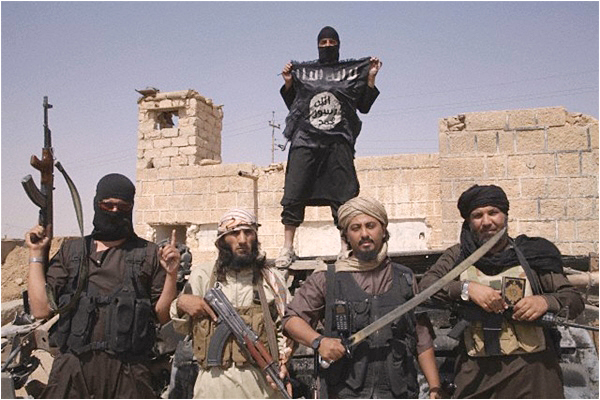

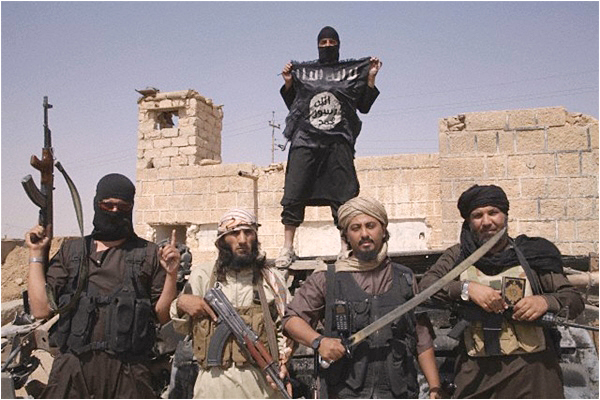

ISIS is being widely projected, in the words of the former U.S. ambassador to Iraq Ryan Crocker, as an “existentialist enemy.” Analysts have cited the adoption of an Islamic title by its leader, its control of territory, its brutality towards women and minorities, and its beheading of prisoners to underline its unprecedented nature.

But how quickly we seem to have forgotten that only a few short years ago, Mullah Omar was given the title of leader of the Muslims (Amir Al-Mu’minin), controlled territory first in Kandahar and then in Kabul, and treated women and minorities brutally. As far as beheadings go, the Pakistani Taliban—who had their own “Amir”—are as brutal as ISIS. In one particularly gruesome act, they beheaded 23 soldiers of the Pakistan army and filmed themselves playing football with their heads.

The same pattern—with leaders adopting similar Islamic titles—can be found among other Muslim tribal groups like Al Shabab in East Africa and Boko Haram in West Africa.

Tribal Islam

What Washington has not been able to wrap its mind around is the fact that tribal people like those that form ISIS live in a particular culture and society. They identify themselves as Muslim and take great pride in that fact, but they also take similar pride in their identity as tribal people. While most analysts look to religion—Islam and the Quran—to describe these societies, they almost entirely miss their tribal character. Without it, it is impossible to make sense of ISIS or the tribal societies in other parts of the Muslim world where America has taken military action since 9/11.

The Code of Honor

The core feature that defines Muslim tribal people—including those fighting under the banner of ISIS—across the Muslim world is belonging to a particular family or clan group who all believe they are descended from a common ancestor. Their actions are defined by a code of honor which emphasizes hospitality towards strangers, bravery and courage in battle, and, crucially, revenge.

It is on this point that the tribal code so frequently trumps Islam. In Muslim tribal societies, if someone kills a member of one’s family or tribe, members of that family or tribe are obligated to kill a member of the offender’s clan or tribe. Though brutal and peremptory—frontier justice at best—the code provided a kind of stability for centuries to these tribal societies.

Although Islam categorically forbids the taking of revenge, the code has prevailed in tribal societies since the coming of Islam 1,400 years ago.

Center and Periphery

In my recent book, The Thistle and the Drone: How America’s War on Terror Became a Global War on Tribal Islam, I examined 40 case studies of tribal societies across the Muslim world from Morocco to the Caucasus. Upholding these societies were three pillars of authority and leadership: respected tribal leaders, religious leaders especially committed to mediation between warring clans, and representatives of central government authority.

These tribes have traditionally lived in remote regions in mountains and deserts often along borders between states. Considering their desire to maintain their codes and customs and the desire of the central government to directly govern all parts of its territory, relations between the two have invariably been difficult.

It should be noted that the support of ISIS comes from tribal groups almost exclusively in what is the periphery in both Iraq and Syria. The failure of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and of former Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki to deal with the tribes fairly as respected citizens of the state provided the catalyst for the growth of ISIS. In short, the eastern tribes of Syria are fighting the central government in Damascus, and the western tribes of Iraq are fighting the central government in Baghdad.

The Importance of History

None of these tribal societies can be understood without placing them in the context of recent history, especially where it connects with the last days of colonization. It was then that imperial officers created boundaries and conjured up new states. The Sykes-Picot agreement after the First World War is directly responsible for the havoc that was almost guaranteed in the Middle East in the way the boundaries and borders were drawn. New nations were created and entire tribes were cut, splitting brother from brother. The tribes which extended on both sides of the border between Iraq and Syria were no exception.

Perhaps the most unfair example of the division of a tribal nation is that of the Kurds. The Kurds have always had a very strong case for their own nation—they have a common language, territory, history, and culture—but were split into half a dozen states including Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and Syria. The Kurds have been very poorly treated by the central authority in each state. It is only with the very strong support of the Americans recently that the Kurds have had some breathing space in north Iraq and live with some dignity and autonomy.

The ghost of Sykes-Picot hovers over the Middle East. It is no coincidence that one of the first actions of the leader of ISIS, when he captured territory on both sides of the Syria/Iraq border, was to jubilantly declare Sykes-Picot to be dead and buried.

The Breakdown of the Tribal Code and Society

Over the last decades, but escalating after 9/11, the conflict between center and periphery has created so much violence that the traditional code of the tribes has broken down. What has remained, in a mutated form, is the notion of revenge. There is a mathematical rhythm to the gruesome killings by groups like ISIS and the Taliban as revenge for military action against them, including airstrikes. ISIS has repeatedly used social media to announce that its barbaric beheadings are acts of revenge. The Pakistan Taliban make exactly the same pronouncement of revenge in relation to the military actions of the central government or American drone strikes.

It is well to keep in mind that not all members of a particular tribal society on the periphery support militant groups like ISIS or the Taliban. It is the ordinary men, women, children, whether they are Muslim or non-Muslim, in these areas who are often the victims of the militants. The lives of these ordinary citizens have been severely disrupted by the violence originating from militant groups but also the security forces of the central government and America and its allies.

Taking the First Step

The first step for Washington is to understand the tribal context of ISIS—and others like it—in order to defeat it. Without recognizing its tribal base, its relationship to both the periphery and the center, and the breakdown which is the cause of its existence, the present strategy will remain ultimately ineffective. There is then no escaping the logic of Einstein’s maxim. n

This article originally appeared in Politico on November 13, 2014.

Ambassador Akbar Ahmed is the Chair of Islamic Studies at American University. He served as Pakistani Ambassador to the United Kingdom and was in charge of administering tribal regions in Waziristan and Baluchistan. He is the author of many books including, most recently, The Thistle and the Drone: How America’s War on Terror Became a Global War on Tribal Islam (Brookings Institution Press, 2013).

It is this basic confusion about the nature of ISIS that is putting Washington in danger of failing yet again in the Middle East. The United States seems to have ignored the famous definition of insanity, which is to make the same mistake again and again and hope for a different result. America has within the last few years gone into countries including Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Somalia, and Yemen to fight against Muslim tribal groups. In each case, these societies are currently in chaos and the groups that were the target of the Americans continue to play havoc and spread violence. The new player, which calls itself the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, is yet another example of a tribal group now involved in a direct military confrontation with the United States and its allies.

Events this week pointed up the need to better understand the nature of the enemy if the United States is to win its new war in the Middle East. After Iraqi officials reported that ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi had been wounded in a U.S. airstrike, he apparently emerged in an audio recording Thursday calling for new “volcanoes of jihad” all over the world. A moment of possible triumph appeared to turn into another recruiting opportunity for the jihadists. Another report suggested that ISIS had formed an alliance with a faction of al Qaeda in Syria.

As far as beheadings go, the Pakistani Taliban are as brutal as ISIS

So just who are these people?

Not Getting the Name Right

Obama—and his administration—are not even sure what the name of the enemy is. Obama calls the entity ISIL. His administration talks of ISIS. In one joint news conference, Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel referred to the group as ISIL and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs General Martin Dempsey called it ISIS. Others call it IS or the Islamic State. The group refers to itself as daiish, which is an Arabic acronym for the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria.

The naming of the enemy may be little more than semantics in the course of events of such global import. Yet it is an indication of the confusion that surrounds the subject of ISIS (let us call it that for the purposes of this article—even though POLITICO normally follows the style of the Associated Press, which uses ISIL).

The Scale of the Threat

There is no unanimity on the scale of the threat either. Obama has said that there is no intelligence that is planning any attacks in the United States. ISIS, however, is described in the U.S. media as the greatest threat to the homeland. Senator Lindsey Graham, the Republican from South Carolina, predicted that ISIS would “open the gates of hell” and told Obama to act before “we all get killed back here at home.” Congressmen have actually declared that “ISIS fighters” were caught trying to cross the southern border. Adding to the confusion, the Department of Homeland Security denied that this had occurred.

An “Existentialist Enemy”?

ISIS is being widely projected, in the words of the former U.S. ambassador to Iraq Ryan Crocker, as an “existentialist enemy.” Analysts have cited the adoption of an Islamic title by its leader, its control of territory, its brutality towards women and minorities, and its beheading of prisoners to underline its unprecedented nature.

But how quickly we seem to have forgotten that only a few short years ago, Mullah Omar was given the title of leader of the Muslims (Amir Al-Mu’minin), controlled territory first in Kandahar and then in Kabul, and treated women and minorities brutally. As far as beheadings go, the Pakistani Taliban—who had their own “Amir”—are as brutal as ISIS. In one particularly gruesome act, they beheaded 23 soldiers of the Pakistan army and filmed themselves playing football with their heads.

The same pattern—with leaders adopting similar Islamic titles—can be found among other Muslim tribal groups like Al Shabab in East Africa and Boko Haram in West Africa.

Tribal Islam

What Washington has not been able to wrap its mind around is the fact that tribal people like those that form ISIS live in a particular culture and society. They identify themselves as Muslim and take great pride in that fact, but they also take similar pride in their identity as tribal people. While most analysts look to religion—Islam and the Quran—to describe these societies, they almost entirely miss their tribal character. Without it, it is impossible to make sense of ISIS or the tribal societies in other parts of the Muslim world where America has taken military action since 9/11.

The Code of Honor

The core feature that defines Muslim tribal people—including those fighting under the banner of ISIS—across the Muslim world is belonging to a particular family or clan group who all believe they are descended from a common ancestor. Their actions are defined by a code of honor which emphasizes hospitality towards strangers, bravery and courage in battle, and, crucially, revenge.

It is on this point that the tribal code so frequently trumps Islam. In Muslim tribal societies, if someone kills a member of one’s family or tribe, members of that family or tribe are obligated to kill a member of the offender’s clan or tribe. Though brutal and peremptory—frontier justice at best—the code provided a kind of stability for centuries to these tribal societies.

Although Islam categorically forbids the taking of revenge, the code has prevailed in tribal societies since the coming of Islam 1,400 years ago.

The traditional code of the tribes has broken down. What has remained, in a mutated form, is the notion of revenge

Center and Periphery

In my recent book, The Thistle and the Drone: How America’s War on Terror Became a Global War on Tribal Islam, I examined 40 case studies of tribal societies across the Muslim world from Morocco to the Caucasus. Upholding these societies were three pillars of authority and leadership: respected tribal leaders, religious leaders especially committed to mediation between warring clans, and representatives of central government authority.

These tribes have traditionally lived in remote regions in mountains and deserts often along borders between states. Considering their desire to maintain their codes and customs and the desire of the central government to directly govern all parts of its territory, relations between the two have invariably been difficult.

It should be noted that the support of ISIS comes from tribal groups almost exclusively in what is the periphery in both Iraq and Syria. The failure of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and of former Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki to deal with the tribes fairly as respected citizens of the state provided the catalyst for the growth of ISIS. In short, the eastern tribes of Syria are fighting the central government in Damascus, and the western tribes of Iraq are fighting the central government in Baghdad.

The Importance of History

None of these tribal societies can be understood without placing them in the context of recent history, especially where it connects with the last days of colonization. It was then that imperial officers created boundaries and conjured up new states. The Sykes-Picot agreement after the First World War is directly responsible for the havoc that was almost guaranteed in the Middle East in the way the boundaries and borders were drawn. New nations were created and entire tribes were cut, splitting brother from brother. The tribes which extended on both sides of the border between Iraq and Syria were no exception.

Perhaps the most unfair example of the division of a tribal nation is that of the Kurds. The Kurds have always had a very strong case for their own nation—they have a common language, territory, history, and culture—but were split into half a dozen states including Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and Syria. The Kurds have been very poorly treated by the central authority in each state. It is only with the very strong support of the Americans recently that the Kurds have had some breathing space in north Iraq and live with some dignity and autonomy.

The ghost of Sykes-Picot hovers over the Middle East. It is no coincidence that one of the first actions of the leader of ISIS, when he captured territory on both sides of the Syria/Iraq border, was to jubilantly declare Sykes-Picot to be dead and buried.

The Breakdown of the Tribal Code and Society

Over the last decades, but escalating after 9/11, the conflict between center and periphery has created so much violence that the traditional code of the tribes has broken down. What has remained, in a mutated form, is the notion of revenge. There is a mathematical rhythm to the gruesome killings by groups like ISIS and the Taliban as revenge for military action against them, including airstrikes. ISIS has repeatedly used social media to announce that its barbaric beheadings are acts of revenge. The Pakistan Taliban make exactly the same pronouncement of revenge in relation to the military actions of the central government or American drone strikes.

It is well to keep in mind that not all members of a particular tribal society on the periphery support militant groups like ISIS or the Taliban. It is the ordinary men, women, children, whether they are Muslim or non-Muslim, in these areas who are often the victims of the militants. The lives of these ordinary citizens have been severely disrupted by the violence originating from militant groups but also the security forces of the central government and America and its allies.

Taking the First Step

The first step for Washington is to understand the tribal context of ISIS—and others like it—in order to defeat it. Without recognizing its tribal base, its relationship to both the periphery and the center, and the breakdown which is the cause of its existence, the present strategy will remain ultimately ineffective. There is then no escaping the logic of Einstein’s maxim. n

This article originally appeared in Politico on November 13, 2014.

Ambassador Akbar Ahmed is the Chair of Islamic Studies at American University. He served as Pakistani Ambassador to the United Kingdom and was in charge of administering tribal regions in Waziristan and Baluchistan. He is the author of many books including, most recently, The Thistle and the Drone: How America’s War on Terror Became a Global War on Tribal Islam (Brookings Institution Press, 2013).