"O you who have believed, be persistently standing firm in justice, witnesses for Allah, even if it be against yourselves or parents and relatives. (Quran 4:135)

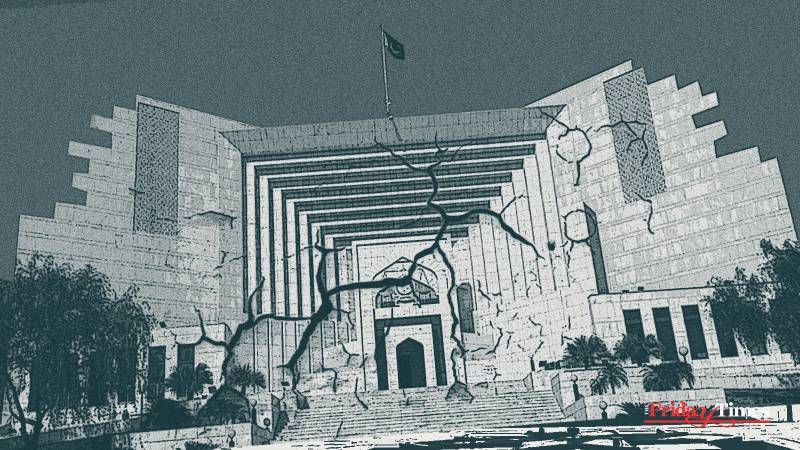

I had planned to write this essay to celebrate the elevation of Justice Mansoor Ali Shah as the Chief Justice of Pakistan (CJP). However, in an unexpected turn of events, the government amended the Constitution, changed the law, and nominated the third-most-senior judge on the seniority list as the CJP. While it is disappointing not to see a jurist of Justice Mansoor Ali Shah's caliber become the CJP, the destruction of institutions and the rule of law is a far more serious concern. The former can be accepted with resignation, but the latter demands immediate attention, careful analysis, and a strong response from both within and outside the judiciary.

Many justices on the bench, like Justice Shah, have been working on strengthening the judiciary. However, the challenges Justice Shah and his court now face transcend administrative reforms. These challenges go to the very heart of our political system and will define whether Pakistan moves towards a just future or remains stuck in the shadows of its past.

This is an open letter to the Justices of the Supreme Court of Pakistan highlighting the challenges they face and the great responsibilities that rest on their shoulders.

In Pakistan, the military establishment, much like Hafiz al-Asad's regime in Syria, rules without any notion of conventional legitimacy. We frequently see politicians being abducted, journalists tortured, and dissenters silenced - actions that, in a typical democracy, would severely undermine the regime's legitimacy

Rule without belief?

There were some rumors that the Special Parliamentary Committee was - despite the amendment - likely to appoint Justice Mansoor Ali Shah as the next CJP to avoid backlash from lawyers and the judiciary at large. However, it did not happen. Why? From a utilitarian standpoint, it would have been a rational choice to make Justice Shah the CJP and nominate another judge as the head of the constitutional bench. This would have given some legitimacy to the system. Why didn't this happen? This is what we must understand.

In Pakistan, the military establishment, much like Hafiz al-Asad's regime in Syria, rules without any notion of conventional legitimacy. We frequently see politicians being abducted, journalists tortured, and dissenters silenced - actions that, in a typical democracy, would severely undermine the regime's legitimacy. However, the crucial insight from Lisa Wedeen's analysis of Syria is that such systems don't actually require legitimacy to function. Instead, they operate through what Wedeen terms "disciplinary-symbolic control."

This system of control in Pakistan, reminiscent of Syria and some other dictatorships or controlled democracies, doesn't aim to create genuine belief in the regime's right to rule. Rather, it enforces a "politics of 'as if'" - where citizens and institutions act as if they revere the constitution and democratic norms while these principles are routinely violated. The military establishment maintains power not through popular support or belief in its legitimacy but by creating a disciplinary environment where public compliance masks private dissent. The latest manifestation is the appointment of Justice Yahya Afridi as the CJP which lets everyone in Pakistan know that the military establishment does not care about any reaction from lawyers or civil society if they sideline Justice Shah.

Dear Justices of SCP

This is the complex political landscape that you are facing now. It makes your job challenging and leaves you with an opportunity to uphold the Constitution with dignity. Let me be clear that your role at the helm of Pakistan's constitutional court is not merely to interpret the law but to navigate a system where symbolic displays of power often supersede legal statutes. The notion that superior court justices’ role is solely to interpret the law is, in this context, as naïve as assuming that Asad's cult in Syria was meant to create genuine belief.

The Constitution that the Supreme Court is tasked with protecting is not just a legal document but a political one, subject to the same kind of symbolic manipulation. It has been alternately revered and disregarded, amended and suspended, depending on the military establishment's needs. Your challenge, therefore, is twofold: you must, like intelligent anthropologists of your own society, read the past with a critical eye, understanding the historical forces and symbolic practices that have brought Pakistan to its current state. Simultaneously, you must work to create conditions that safeguard the Constitution's future, aware that your decisions today will set precedents that could either fortify or further weaken Pakistan's democratic foundations.

While there are limits to what two dozen judges can actively do to shape policy or governance, the power to prevent unconstitutional actions is significant. This is where the expectations for the current reformist judges are highest - in your capacity to halt the erosion of constitutional norms and prevent further disrespect to the country's supreme law. By standing firm against attempts to circumvent or undermine the constitution, whether from political, military, or other powerful quarters, you have the opportunity to challenge the "politics of 'as if'" and strengthen the judiciary's role as a bulwark against autocracy.

Reclaiming politics

One crucial way of upholding the Constitution in a system of disciplinary-symbolic control is to create and facilitate enabling conditions for people's right to political activity. This right extends far beyond the mere right to protest; it encompasses the broader spectrum of political expression, ensuring that people have a protected public sphere in which their voices can be heard without fear of reprisal. In Pakistan, where the military establishment often rules through a "politics of 'as if,'" protecting genuine political activity–unblocking X (the social media platform formerly known as Twitter), for example— becomes even more critical. It challenges the facade of democracy that the system maintains and pushes back against the enforced public compliance that masks private dissent.

In this context, a strong, politically engaged public becomes not just a cornerstone of functional democracy but a direct challenge to the system of symbolic power. A parliament that genuinely represents the people's will is less likely to be co-opted by the military establishment or other external forces. Similarly, an awakened and active populace serves as a bulwark for the judiciary, standing in defense of judicial independence when it's threatened. This is particularly important in Pakistan, where power often operates through extra-legal means and symbolic displays.

Protecting political activity, therefore, is not just about safeguarding individual rights; it's about disrupting the "politics of 'as if'" and creating spaces for genuine democratic practice. It's a way for the judiciary, led by figures like Justice Shah, to assert the power of LAW in a landscape where power often operates through symbolic manipulation. By ensuring that people can engage in real political activity - not just performative displays of compliance - the judiciary can help create conditions where the rule of law begins to take precedence over the rule of symbolic power. The underlying idea is that while the system may not require conventional legitimacy to function, protecting and encouraging genuine political engagement can gradually erode the effectiveness of disciplinary-symbolic control, paving the way for more authentic democratic processes.

Beyond judgments: Disrupting symbolic power

Dear Justices,

Your legacy will likely be measured not just by the judgments you make but by how effectively you can navigate and potentially disrupt the system of symbolic power that often supersedes legal frameworks in Pakistan's governance. In doing so, you may be able to create spaces for genuine democratic practice rather than mere performances of democracy. The task before you is not to create legitimacy for a system that doesn't require it but to assert the power of constitutional law in a landscape where power often operates through extra-legal means.

In essence, your role is to read the past, understand the present, and help create conditions where the future doesn't disrespect the Constitution the way the past has done several times. While there's not so much a Court can do to reshape the political landscape actively, there is much judges can stop from happening. This is what we expect from the justices on the bench: to stop the disrespect of the Constitution and to create a space where the rule of law can begin to take precedence over the rule of symbolic power.

The first step in this regard would be a careful judicial review of the 26th Amendment to examine whether it aligns with constitutional principles, particularly judicial independence. The Supreme Court, through collective wisdom, can chart a path that respects both parliamentary legislative authority and the judiciary's independence.