The recent spate of hate mongering orchestrated by Shiv Sena in India has led to euphoric expressions of self-vindication by the firebrands in Pakistan. They did not waste a moment in declaring that this was proof of their own theory of a religion-based divide. The surge in communalism in India is a blot on the image of the world’s largest secular democracy, but the reaction of the Indian literati and civil society also demands some introspection on our part. They have vehemently condemned extremism and expressed a resolve to go to any extent to save the secular countenance of India.

The scale of a society’s reaction to bigotry and intolerance is the true barometer of its commitment to the fundamental values of respect for human dignity and the right to profess any faith. Unfortunately, the reaction of the Pakistani society against intolerance and extremism in their own country has not been as loud and clear as it ought to be, such as in the case of tragic violence against a religious minority in Jhelum. That is a real matter of concern. The upsurge of intolerance in India does not mean everything is perfect in our own part of the world.

The most positive development in Pakistan in recent times is the belated but necessary change in the policies of the state and a general consensus against terrorism. The new policy was translated into a clear set of objectives in the prime minister’s National Action Plan. Apart from carrying out surgical strikes against various centers of terror, the state also decided to ban hate speech and carry out madrassa reforms. The progress against the infrastructure of terror is laudable and visible, but there is a lot to be done to de-radicalize the society. That requires not just government action, but a resolve on the part of the academia, the civil society, the media, and every other notable segment of the society.

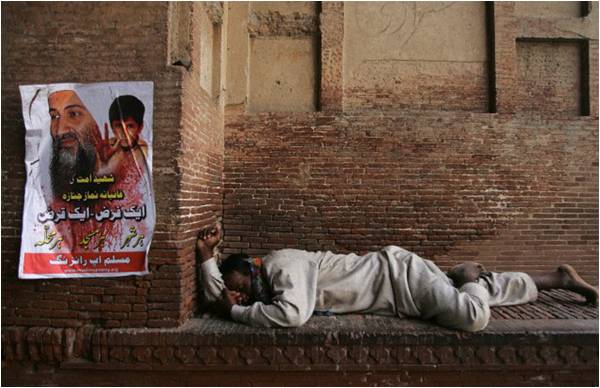

Religious extremism has infiltrated the society in the form of an ideology, and the only way to counter an ideology is to propagate a more potent and convincing ideology against it. The contemporary form of religious terrorism stems from scholarship of ideologues like Sayyid Qutb of Egypt. The concept of “Jahilliya” expounded by Qutb meant that secular Muslims are in a state of ignorance and are the “near enemy”, compared with non-Muslims, who are the “distant enemies”. This concept was taken to a further extreme by Arab radicals like Abdullah Azzam and Ayman al Zawahiri, who preached “Takfir” – justifying killings of non-Muslims and secular Muslims alike. This ideology became entrenched in those seminaries in Pakistan that were part of the supply chain of radical fighters who fought against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan. In the last decade, they have unleashed terror in Pakistan. The brutal massacre of innocent schoolchildren in Peshawar last year was among the worst manifestations of this way of thinking. A physical war against the followers of this ideology is just one element of the solution. A total solution requires complementing this effort with a powerful counter-narrative.

Tragic incidents of mass violence against religious minorities in Lahore’s Joseph Colony, Kot Radha Kishan and Jhelum indicate that extremist ideology has grown deep roots in the society. A number of suspects arrested for being part of banned international terrorist groups in Pakistan recently are highly educated. Many of them were engineers and teachers.

But the hard-won consensus against militancy should be seen as an opportunity to launch a massive diagnostic exercise, to find out when and what went wrong in our journey as a nation. The charter laid down in Quaid-e-Azam’s famous speech of 11th August 1947 should be the yardstick. Intellectuals and scholars from all sections of the society should be engaged in this exercise, to help frame a new national narrative. Voices of rationality and moderation should be given due breathing space. The media should be encouraged to play their due role in social transformation, such as that played by the Tatler and the Spectator in the nineteenth century England.

Revamping of the mainstream curriculum as well as that of madrassas should form the nucleus of this national effort. And last but not the least, the focus of governance should be on the dispensation of social justice, the absence of which brews unrest and intolerance.

Without a reinvented state narrative, the implementation of the National Action Plan may provide a temporary respite, but it will stay short of that change that is vital for our survival as a progressive nation.

The scale of a society’s reaction to bigotry and intolerance is the true barometer of its commitment to the fundamental values of respect for human dignity and the right to profess any faith. Unfortunately, the reaction of the Pakistani society against intolerance and extremism in their own country has not been as loud and clear as it ought to be, such as in the case of tragic violence against a religious minority in Jhelum. That is a real matter of concern. The upsurge of intolerance in India does not mean everything is perfect in our own part of the world.

The most positive development in Pakistan in recent times is the belated but necessary change in the policies of the state and a general consensus against terrorism. The new policy was translated into a clear set of objectives in the prime minister’s National Action Plan. Apart from carrying out surgical strikes against various centers of terror, the state also decided to ban hate speech and carry out madrassa reforms. The progress against the infrastructure of terror is laudable and visible, but there is a lot to be done to de-radicalize the society. That requires not just government action, but a resolve on the part of the academia, the civil society, the media, and every other notable segment of the society.

Religious extremism has infiltrated the society in the form of an ideology, and the only way to counter an ideology is to propagate a more potent and convincing ideology against it. The contemporary form of religious terrorism stems from scholarship of ideologues like Sayyid Qutb of Egypt. The concept of “Jahilliya” expounded by Qutb meant that secular Muslims are in a state of ignorance and are the “near enemy”, compared with non-Muslims, who are the “distant enemies”. This concept was taken to a further extreme by Arab radicals like Abdullah Azzam and Ayman al Zawahiri, who preached “Takfir” – justifying killings of non-Muslims and secular Muslims alike. This ideology became entrenched in those seminaries in Pakistan that were part of the supply chain of radical fighters who fought against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan. In the last decade, they have unleashed terror in Pakistan. The brutal massacre of innocent schoolchildren in Peshawar last year was among the worst manifestations of this way of thinking. A physical war against the followers of this ideology is just one element of the solution. A total solution requires complementing this effort with a powerful counter-narrative.

The focus of governance should be on social justice

Tragic incidents of mass violence against religious minorities in Lahore’s Joseph Colony, Kot Radha Kishan and Jhelum indicate that extremist ideology has grown deep roots in the society. A number of suspects arrested for being part of banned international terrorist groups in Pakistan recently are highly educated. Many of them were engineers and teachers.

But the hard-won consensus against militancy should be seen as an opportunity to launch a massive diagnostic exercise, to find out when and what went wrong in our journey as a nation. The charter laid down in Quaid-e-Azam’s famous speech of 11th August 1947 should be the yardstick. Intellectuals and scholars from all sections of the society should be engaged in this exercise, to help frame a new national narrative. Voices of rationality and moderation should be given due breathing space. The media should be encouraged to play their due role in social transformation, such as that played by the Tatler and the Spectator in the nineteenth century England.

Revamping of the mainstream curriculum as well as that of madrassas should form the nucleus of this national effort. And last but not the least, the focus of governance should be on the dispensation of social justice, the absence of which brews unrest and intolerance.

Without a reinvented state narrative, the implementation of the National Action Plan may provide a temporary respite, but it will stay short of that change that is vital for our survival as a progressive nation.