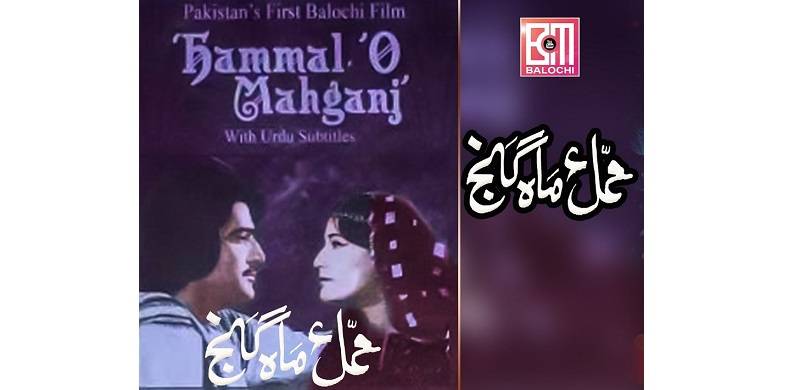

Some 47 years ago, back in 1976, the first Balochi feature film Hammal o Mahganj, based on a Baloch folktale of love and resistance, was made by the prominent TV actor Anwer Iqbal. The movie was subject to protests due to its misleading display against Baloch culture. This halted the evolution of Balochi film and deepened an androcentric culture in the industry, which still prevails. It took 10 years for Balochi films to be revived back on screen.

In 1985, the film Gall o Kandag was released. With 10 years having elapsed, Balochi once again was resuscitating in a movie. The film evoked the societal and political disorganisation of the region. Gall o Kandag revitalised the Baloch industry with masculine dominance. And till now, Baloch women still have doubts about playing a movie character on screen.

Another film Thanz Gir (The Taunter) was released in 1986 and was watched in Karachi, Balochistan, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The film made a name for itself and earned a viewership from diverse groups. At the same time, an Iranian film Dadshah, dubbed in Balochi, was receiving accolades from all over Balochistan. This was the second wave of Balochi cinema. Though it was a slow-going and male-centered rise, yet it left smiles on Baloch lives to see Balochi an arising tongue in the industry. After these films, Baloch artists dubbed several Hindi and English movies into Balochi, including Delhi Separi, Pishuk, Sherok, Ramo Ruliya, Young Liyari and many others.

From 1985 till 2010, the Balochi film industry has celebrated hundreds of releases, sketching the political, socioeconomic, social, psychological, literary and human-rights related crises in Balochistan. Numerous films were made to highlight womens rights – but without womens participation in the films.

From 1985 till 2010, the Balochi film industry has celebrated hundreds of releases, sketching the political, socioeconomic, social, psychological, literary and human-rights related crises in Balochistan. Numerous films were made to highlight womens rights – but without womens participation in the films.

Some other famed movies including Sheikh Chilli, Dubai Kassi Nabi (Dubai Is No-ones), Karachi Mara Na Sachi (Karachi Doesnt Please Us), Nako Commando (Uncle Commando) – starring Waqar Baloch, Naeem Nisar, Dur Muhammad Africi, Wali Raees and others – made good names for themselves.

Ebitan Umer in his book Drama and Balochi Drama writes that Yousuf Jans Tamasha movie released in 1993 was the first Balochi film after Hammal o Mahganj which introduced some female characters who were scripted to deliver Urdu and Sindhi dialogues to avoid criticism and protest from the people. The cast of the movie included Waqar Baloch, Yousuf Jan, Danish Baloch, Saghar Siddique, Qadir Hassni, Zubair Thakur. The end of the 20th century was a gifted period for Balochi films, as the competition was less, and so was the criticism. However, the 21st century was an appalling era for the young Baloch filmmakers.

In 2000, Danish Baloch's Aasty Aasty Shar Be was made. Simultaneously, Ganjein Gwadar (Treasured Gwadar) and Maye Gwadar (Our Gwadar) were on screens in every house in Balochistan and nationwide, including in the Persian Gulf countries. The two films highlighted the woes of locals in the city. After the two movies, several others including Dishtaar (Fiance), Aadenk (The mirror), Rahdarbar (The Guide), Armaan (The Pity) and Aas (The fire) were successful releases. Filmmaking in Balochistan at the beginning of the 21st century was one of the ways for indigenous people to highlight social issues.

Filmmaking attracted a number of young artists in different cities of Balochistan later on. For instance, Homar Kiyya and Hanif Sharif from district Turbat (Kech) led another group of young filmmakers, charming on screens. Sharifs films Balochistan Hotel, Mani Peth a Brath Nest (My Father Has No Brother) and Balaach appeared to have received new levels of acclaim, and are watched till now with ever-growing appreciation due to his literary sagacity. Hanif Sharif is one of the most critical film directors and scriptwriters in the contemporary Balochi film industry. His works, however, have always been leading masculine characters as of others.

Baloch artists from different cities in Balochistan and Karachi were seeking a rise of Balochi cinema by introducing multiple new works on screen. In 2010, from Lyari, Balochi short filmmaking emerged. Short films such as Hasht Roch (Eight Days), Washdil, Garh Garh, Aazman (The Sky) and Shoom (The unfortunate) were the best releases of the year, which were based on psychological, political, economic and human-rights related issues in Lyari. Of them, Hasht Roch was nominated for the best short film of the year and won the Aga Khan Award.

Another short film Jawar (The Situation) was directed by Ehsan Shah in 2016. The movie depicteded the ongoing situation in Lyari at the time. However, due to its screenplay and direction, the film received the Bahrain International Youth Award, winning against 130 other nominees. It was a long journey of hard wins for Baloch artists, despite having never been cheered in the mainstream media nationally.

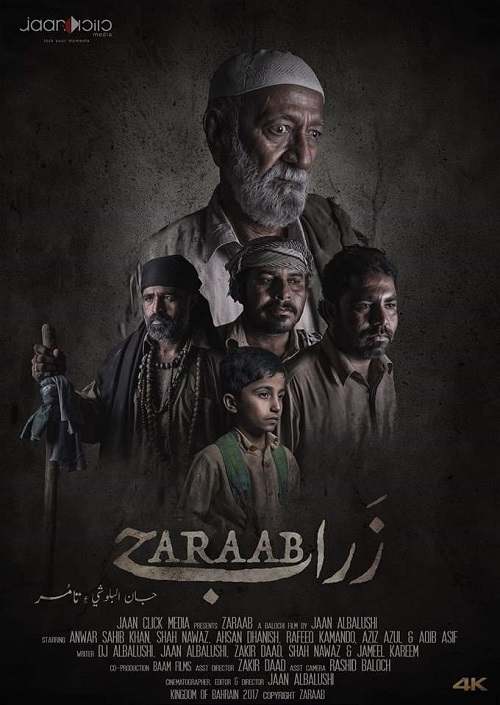

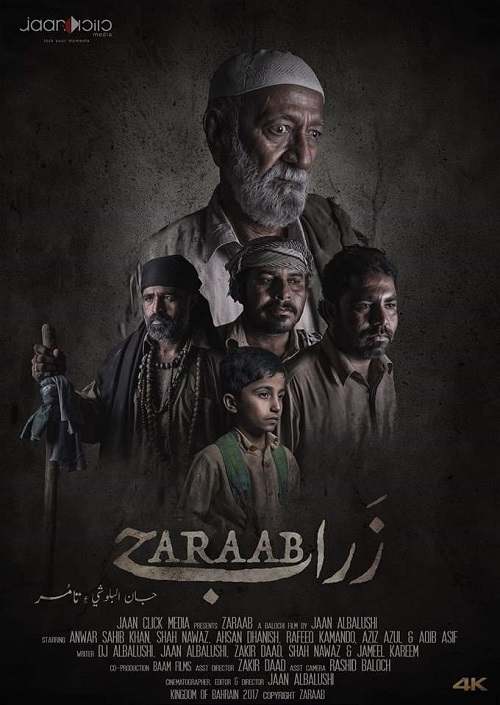

In 2018, Zaraab (The Heat), the first Balochi feature film that reached big screen, was screened all across Balochistan after it had already been screened initially in Bahrain. The movie was directed by an award-winning Bahrain-based filmmaker and photographer Jaan Albaloshi. It features the famed and legendary Baloch poet and actor Mama Anwer Sahib Khan (late), Shahnwaz Shah, Ehsan Danish and Aqib Asif. The film highlights the great depression of four individuals belonging to a family in Gwadar. It gives a clear image of anxieties and the plight of the locals. Yet again, Zaraab, despite being the first feature film screened internationally, also had an all-male cast. Nevertheless, the movie was shortlisted for an international film festival in 2018 and won some other awards.

Appreciated by the film experts nationally and internationally, Zaraab gave Balochi cinema a relish of cinematography, intricate melody and a cinematic look. Adeel Raees served played an important role in Balochi cinema around this time too. His films To Win Zato and Poster were two of the award-winning movies. To Win Zato was named the best film in the Lyari Film Festival, while Poster was awarded The Best Audience Award in Italy’s International Film Festival. Raees works mainly mirror the plight of locals in Lyari. Both his works are silent movies and, as such, Raees is considered the first Baloch filmmaker who has first-ever produced silent movies.

Lyari has been one of the largest contributing regions to Balochi cinema. Films such as Working Women of Lyari, Hidden Diamond of Lyari and Prison Without Wall are some blockbuster hits. Makran division was the second largest zone for Balochi cinema. Kamalan Bebagr, an emerging young filmmaker from Turbat, added another big screen work Malaar to Balochi cinema. The movie manifested the psychological distress in society. Released on Eid al-Adha in 2020, the film featured Homer Kiyya, Rashid Hassan and Rafiq Gul. It was the second feature movie that Baloch people had waited for after Zaraab. Malaar was later released on YouTube on 20 December 2020.

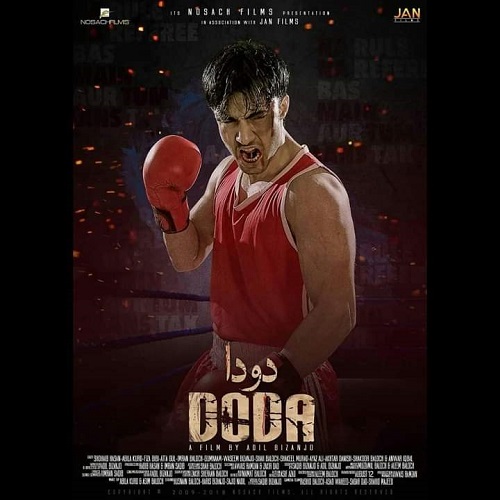

After 2015, Baloch artists worked to develop a modern cinema culture, contending for the attention of international critics and audiences. It would be justified to say that they did, indeed, succeed. Balochi films were in a good place when Doda, another feature film directed by Adil Bezinjo, assumed hefty significance. The movie sketches the tale of a Lyari-based young boxer and Shoaib Hassan plays the eponymous hero in the film. However, the film has not premiered on YouTube yet.

After 2015, Baloch artists worked to develop a modern cinema culture, contending for the attention of international critics and audiences. It would be justified to say that they did, indeed, succeed. Balochi films were in a good place when Doda, another feature film directed by Adil Bezinjo, assumed hefty significance. The movie sketches the tale of a Lyari-based young boxer and Shoaib Hassan plays the eponymous hero in the film. However, the film has not premiered on YouTube yet.

Spanish actor and director Antonio Banderas states, "Cinema has opened a world of possibilities up for me." Cinema translates great depression into progressive narratives. It is worldwide considered a driver of social reform. Though cinema in Balochistan has dealt with many severe challenges, not least of which are financial problems, filmmaking continues to take root.

A number of young Baloch filmmakers are studying filmmaking in different institutions in the country. It seems like a rich period of Balochi cinema is in the offing.

In 1985, the film Gall o Kandag was released. With 10 years having elapsed, Balochi once again was resuscitating in a movie. The film evoked the societal and political disorganisation of the region. Gall o Kandag revitalised the Baloch industry with masculine dominance. And till now, Baloch women still have doubts about playing a movie character on screen.

Another film Thanz Gir (The Taunter) was released in 1986 and was watched in Karachi, Balochistan, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The film made a name for itself and earned a viewership from diverse groups. At the same time, an Iranian film Dadshah, dubbed in Balochi, was receiving accolades from all over Balochistan. This was the second wave of Balochi cinema. Though it was a slow-going and male-centered rise, yet it left smiles on Baloch lives to see Balochi an arising tongue in the industry. After these films, Baloch artists dubbed several Hindi and English movies into Balochi, including Delhi Separi, Pishuk, Sherok, Ramo Ruliya, Young Liyari and many others.

From 1985 till 2010, the Balochi film industry has celebrated hundreds of releases, sketching the political, socioeconomic, social, psychological, literary and human-rights related crises in Balochistan. Numerous films were made to highlight womens rights – but without womens participation in the films.

From 1985 till 2010, the Balochi film industry has celebrated hundreds of releases, sketching the political, socioeconomic, social, psychological, literary and human-rights related crises in Balochistan. Numerous films were made to highlight womens rights – but without womens participation in the films.Some other famed movies including Sheikh Chilli, Dubai Kassi Nabi (Dubai Is No-ones), Karachi Mara Na Sachi (Karachi Doesnt Please Us), Nako Commando (Uncle Commando) – starring Waqar Baloch, Naeem Nisar, Dur Muhammad Africi, Wali Raees and others – made good names for themselves.

Ebitan Umer in his book Drama and Balochi Drama writes that Yousuf Jans Tamasha movie released in 1993 was the first Balochi film after Hammal o Mahganj which introduced some female characters who were scripted to deliver Urdu and Sindhi dialogues to avoid criticism and protest from the people. The cast of the movie included Waqar Baloch, Yousuf Jan, Danish Baloch, Saghar Siddique, Qadir Hassni, Zubair Thakur. The end of the 20th century was a gifted period for Balochi films, as the competition was less, and so was the criticism. However, the 21st century was an appalling era for the young Baloch filmmakers.

In 2000, Danish Baloch's Aasty Aasty Shar Be was made. Simultaneously, Ganjein Gwadar (Treasured Gwadar) and Maye Gwadar (Our Gwadar) were on screens in every house in Balochistan and nationwide, including in the Persian Gulf countries. The two films highlighted the woes of locals in the city. After the two movies, several others including Dishtaar (Fiance), Aadenk (The mirror), Rahdarbar (The Guide), Armaan (The Pity) and Aas (The fire) were successful releases. Filmmaking in Balochistan at the beginning of the 21st century was one of the ways for indigenous people to highlight social issues.

Filmmaking attracted a number of young artists in different cities of Balochistan later on. For instance, Homar Kiyya and Hanif Sharif from district Turbat (Kech) led another group of young filmmakers, charming on screens. Sharifs films Balochistan Hotel, Mani Peth a Brath Nest (My Father Has No Brother) and Balaach appeared to have received new levels of acclaim, and are watched till now with ever-growing appreciation due to his literary sagacity. Hanif Sharif is one of the most critical film directors and scriptwriters in the contemporary Balochi film industry. His works, however, have always been leading masculine characters as of others.

Baloch artists from different cities in Balochistan and Karachi were seeking a rise of Balochi cinema by introducing multiple new works on screen. In 2010, from Lyari, Balochi short filmmaking emerged. Short films such as Hasht Roch (Eight Days), Washdil, Garh Garh, Aazman (The Sky) and Shoom (The unfortunate) were the best releases of the year, which were based on psychological, political, economic and human-rights related issues in Lyari. Of them, Hasht Roch was nominated for the best short film of the year and won the Aga Khan Award.

Another short film Jawar (The Situation) was directed by Ehsan Shah in 2016. The movie depicteded the ongoing situation in Lyari at the time. However, due to its screenplay and direction, the film received the Bahrain International Youth Award, winning against 130 other nominees. It was a long journey of hard wins for Baloch artists, despite having never been cheered in the mainstream media nationally.

In 2018, Zaraab (The Heat), the first Balochi feature film that reached big screen, was screened all across Balochistan after it had already been screened initially in Bahrain. The movie was directed by an award-winning Bahrain-based filmmaker and photographer Jaan Albaloshi. It features the famed and legendary Baloch poet and actor Mama Anwer Sahib Khan (late), Shahnwaz Shah, Ehsan Danish and Aqib Asif. The film highlights the great depression of four individuals belonging to a family in Gwadar. It gives a clear image of anxieties and the plight of the locals. Yet again, Zaraab, despite being the first feature film screened internationally, also had an all-male cast. Nevertheless, the movie was shortlisted for an international film festival in 2018 and won some other awards.

Appreciated by the film experts nationally and internationally, Zaraab gave Balochi cinema a relish of cinematography, intricate melody and a cinematic look. Adeel Raees served played an important role in Balochi cinema around this time too. His films To Win Zato and Poster were two of the award-winning movies. To Win Zato was named the best film in the Lyari Film Festival, while Poster was awarded The Best Audience Award in Italy’s International Film Festival. Raees works mainly mirror the plight of locals in Lyari. Both his works are silent movies and, as such, Raees is considered the first Baloch filmmaker who has first-ever produced silent movies.

Lyari has been one of the largest contributing regions to Balochi cinema. Films such as Working Women of Lyari, Hidden Diamond of Lyari and Prison Without Wall are some blockbuster hits. Makran division was the second largest zone for Balochi cinema. Kamalan Bebagr, an emerging young filmmaker from Turbat, added another big screen work Malaar to Balochi cinema. The movie manifested the psychological distress in society. Released on Eid al-Adha in 2020, the film featured Homer Kiyya, Rashid Hassan and Rafiq Gul. It was the second feature movie that Baloch people had waited for after Zaraab. Malaar was later released on YouTube on 20 December 2020.

After 2015, Baloch artists worked to develop a modern cinema culture, contending for the attention of international critics and audiences. It would be justified to say that they did, indeed, succeed. Balochi films were in a good place when Doda, another feature film directed by Adil Bezinjo, assumed hefty significance. The movie sketches the tale of a Lyari-based young boxer and Shoaib Hassan plays the eponymous hero in the film. However, the film has not premiered on YouTube yet.

After 2015, Baloch artists worked to develop a modern cinema culture, contending for the attention of international critics and audiences. It would be justified to say that they did, indeed, succeed. Balochi films were in a good place when Doda, another feature film directed by Adil Bezinjo, assumed hefty significance. The movie sketches the tale of a Lyari-based young boxer and Shoaib Hassan plays the eponymous hero in the film. However, the film has not premiered on YouTube yet.Spanish actor and director Antonio Banderas states, "Cinema has opened a world of possibilities up for me." Cinema translates great depression into progressive narratives. It is worldwide considered a driver of social reform. Though cinema in Balochistan has dealt with many severe challenges, not least of which are financial problems, filmmaking continues to take root.

A number of young Baloch filmmakers are studying filmmaking in different institutions in the country. It seems like a rich period of Balochi cinema is in the offing.