A visibly unstable Altaf Hussain made an apology within hours of a shocking tirade against Pakistan. But the damage is done. With his 20-second statement, he has handed to the state a stick that they had long been waiting for to beat him with. It also resulted in the long-overdue unraveling of a party that is linked with high-handedness, coercion, and brute force.

They have used these tactics for survival, for self-perpetuation, for the persecution of dissenters, and for the projection of their political power as and when necessary. MQM’s history is replete with such shows of strength, as well as fatal political mistakes, miscalculations and a problem-child approach to politics. Altaf Hussain has his own peculiar style of public speaking, that includes everything from singing during a press conference to openly threatening his opponents. His careless statements have often embarrassed his party, and they are expected to come up with something-ridiculous explanations and justifications.

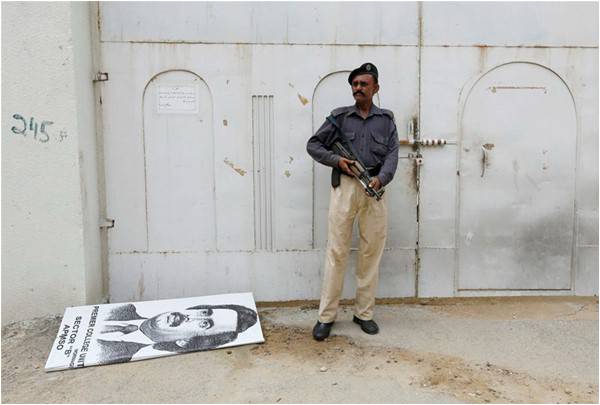

The violence in Karachi on May 12, 2007 stands out as proof for some of the aforementioned “guiding principles” that the MQM cadres had to follow in Karachi.

“Once we received the instructions to prevent (former chief justice) Iftikhar Chaudhry from reaching the Karachi Bar via road, we had to make elaborate arrangements,” an intelligence officer posted in Sindh recalls. “Every pro-Musharraf person and party, including the MQM, were taken on-board for consultation. We were told to let the MQM handle the city. Karachi had been literally handed over to the MQM. We did successfully prevent Chaudhry from getting out of the airport but at the cost of over 40 lives, mostly activists of ANP and PPP,” the officer said. He said they had advised the president not to address a public rally in front of the Parliament that evening (because of the bloodshed in Karachi).

But Musharraf’s aides turned down the advice, he said, and prompted by Chaudhry Shujaat Hussain and his likes, the president raised his fists in the air and said: “We have demonstrated people’s power tonight.”

I remember a conversation with a German friend working in the development sector over a decade and half ago, when Gen (r) Pervez Musharraf had begun to hobnob with Altaf Hussein’s MQM for his own selfish motives. “How can the head of a state reach out to a person wanted on multiple counts by the state itself?” he asked me. “Is a closure of such cases possible before such a party is taken on board?” We had no answer. We just watched in awe with him as Musharraf and his hand-picked prime minister Shuakat Aziz courted MQM leaders and telephoned their guru in London.

The PPP-led government in the mid-90s delivered quite an effective response to the urban violence blamed on the MQM – a crackdown led by the then interior minister Naseerullah Babar and supported by the Intelligence Bureau and the police, targeting armed militants linked to the organization.

“It was an effective move and that is why I requested the then President Farooq Leghari not to disrupt the PPP’s return to power because of the momentum the crackdown had created,” a former police chief told me. His conversation with Leghari took place shortly before the elections of 1997, months after the latter had dismissed the Benazir Bhutto government in November 1996.

A continuation of the PPP government would have meant a continued pressure on the MQM, but the return of Nawaz Sharif and his allies to power in 1997 and the Musharraf coup in October 1999 changed the course of political history, particularly because Musharraf was looking for political crutches to survive and began courting the MQM.

Their detractors say this helped the MQM re-strengthen its armed wing and extortion practices. There is a near-consensus that other parties in the city have also been involved in assassinations and organized crime, such as extortion, abduction and financial blackmail. The MQM however projects itself to be the victim of a witch hunt.

What has happened now could be a big blow to the party, and the federal government can raise the issue of “incitement to violence and hatred” by Altaf Hussain with the British government. Most observers agree that this situation might lead to the total marginalization of its founder. That is why there is no need to ban the party.

The state should sternly follow the rule of law in dealing with the party now. It must shun the policy of appeasement that creates monsters.

It should also let the transition under Farooq Sattar happen. The leaders of the MQM did well to distance themselves from Altaf Hussain without calling him names or attacking him, unlike Mustafa Kamal, who created a new party and began insulting his former boss. This transition needs extremely careful facilitation.

A strong intent rooted in a stringent belief in the rule and enforcement of law, and saying no to appeasement, can transform the MQM and Karachi’s politics.

They have used these tactics for survival, for self-perpetuation, for the persecution of dissenters, and for the projection of their political power as and when necessary. MQM’s history is replete with such shows of strength, as well as fatal political mistakes, miscalculations and a problem-child approach to politics. Altaf Hussain has his own peculiar style of public speaking, that includes everything from singing during a press conference to openly threatening his opponents. His careless statements have often embarrassed his party, and they are expected to come up with something-ridiculous explanations and justifications.

The violence in Karachi on May 12, 2007 stands out as proof for some of the aforementioned “guiding principles” that the MQM cadres had to follow in Karachi.

“Once we received the instructions to prevent (former chief justice) Iftikhar Chaudhry from reaching the Karachi Bar via road, we had to make elaborate arrangements,” an intelligence officer posted in Sindh recalls. “Every pro-Musharraf person and party, including the MQM, were taken on-board for consultation. We were told to let the MQM handle the city. Karachi had been literally handed over to the MQM. We did successfully prevent Chaudhry from getting out of the airport but at the cost of over 40 lives, mostly activists of ANP and PPP,” the officer said. He said they had advised the president not to address a public rally in front of the Parliament that evening (because of the bloodshed in Karachi).

But Musharraf’s aides turned down the advice, he said, and prompted by Chaudhry Shujaat Hussain and his likes, the president raised his fists in the air and said: “We have demonstrated people’s power tonight.”

I remember a conversation with a German friend working in the development sector over a decade and half ago, when Gen (r) Pervez Musharraf had begun to hobnob with Altaf Hussein’s MQM for his own selfish motives. “How can the head of a state reach out to a person wanted on multiple counts by the state itself?” he asked me. “Is a closure of such cases possible before such a party is taken on board?” We had no answer. We just watched in awe with him as Musharraf and his hand-picked prime minister Shuakat Aziz courted MQM leaders and telephoned their guru in London.

The PPP-led government in the mid-90s delivered quite an effective response to the urban violence blamed on the MQM – a crackdown led by the then interior minister Naseerullah Babar and supported by the Intelligence Bureau and the police, targeting armed militants linked to the organization.

“It was an effective move and that is why I requested the then President Farooq Leghari not to disrupt the PPP’s return to power because of the momentum the crackdown had created,” a former police chief told me. His conversation with Leghari took place shortly before the elections of 1997, months after the latter had dismissed the Benazir Bhutto government in November 1996.

A continuation of the PPP government would have meant a continued pressure on the MQM, but the return of Nawaz Sharif and his allies to power in 1997 and the Musharraf coup in October 1999 changed the course of political history, particularly because Musharraf was looking for political crutches to survive and began courting the MQM.

Their detractors say this helped the MQM re-strengthen its armed wing and extortion practices. There is a near-consensus that other parties in the city have also been involved in assassinations and organized crime, such as extortion, abduction and financial blackmail. The MQM however projects itself to be the victim of a witch hunt.

What has happened now could be a big blow to the party, and the federal government can raise the issue of “incitement to violence and hatred” by Altaf Hussain with the British government. Most observers agree that this situation might lead to the total marginalization of its founder. That is why there is no need to ban the party.

The state should sternly follow the rule of law in dealing with the party now. It must shun the policy of appeasement that creates monsters.

It should also let the transition under Farooq Sattar happen. The leaders of the MQM did well to distance themselves from Altaf Hussain without calling him names or attacking him, unlike Mustafa Kamal, who created a new party and began insulting his former boss. This transition needs extremely careful facilitation.

A strong intent rooted in a stringent belief in the rule and enforcement of law, and saying no to appeasement, can transform the MQM and Karachi’s politics.