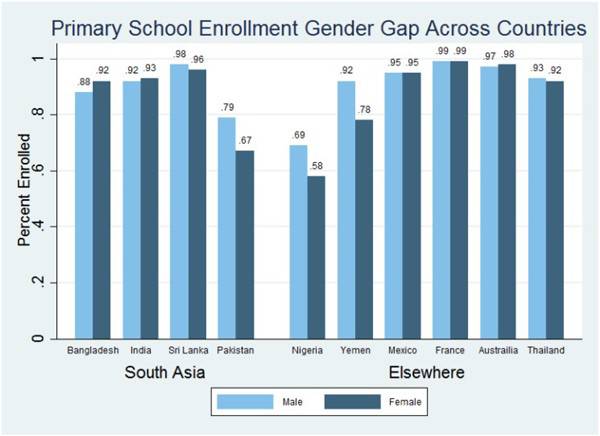

Pakistan’s pervasive gender gap in primary school enrollment puts it behind other South Asian countries including India, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh: 65 percent of Pakistan’s primary-aged girls are enrolled, compared to 77 percent of boys.

This gender gap persists despite the government’s attempts to address it, such as stipend programs to incentivize parents to enroll girls and provincial laws to end gender segregation. These efforts aligned with Education for All (EFA), a global initiative that aimed, among other things, to eliminate gender disparity in primary and secondary education by 2015—a target Pakistan did not meet.

Curiously, the gap persists even as parents across Pakistan voice changing attitudes toward girls’ education. Surveys show more than 8 out of 10 Pakistanis say that education is equally important for boys and girls; very few say that it is more important for boys than girls or the other way round. One of us, Ravale, witnessed this close-up when she conducted focus group discussions with parents and teachers as program manager for Learning and Educational Achievement in Pakistan Schools (LEAPS), a long-running research initiative headed by Tahir Andrabi of Pomona College, Jishnu Das of the World Bank, and Asim I. Khwaja of Harvard Kennedy School and co-director of Evidence for Policy Design.

These focus groups, involving more than 200 parents and teachers of children enrolled in low-cost private schools in rural and urban northern Punjab in 2016, showed that many parents viewed girls’ schooling as a form of protection, and they expected social and financial clout for their daughters as a natural byproduct of education.

Surprisingly, most parents expected higher returns when it came to investing in a daughter’s education as compared to a son’s education, and several said that an education would arm girls to navigate social relations better, especially with in-laws.

The persisting gender gap in primary school enrollment could, then, be due to a misunderstood situation leading to misused funds. If society already shows greater acceptance of girls’ education, then government efforts to inform or incentivize parents may not be useful. On the other hand, if public schools either don’t exist or are too far away for girls to reach, it matters little whether their parents want their daughters to get educated.

The distance penalty

New research from the LEAPS project sheds light on this idea. Most Punjab households have a primary school within 500 meters, but girls’ enrollment plunges with distance while boys’ enrollment descends only slightly. For children who live right next to a school, there is almost no gender difference, but for children who live 100 meters away, a boy is more likely to attend school than a girl. The gap widens from there.

So the act of schooling itself is not at issue—what matters is the societal cost of travel. “You wouldn’t be as surprised to see this hold for adult women, given conservative norms about their mobility,” says Asim I. Khwaja, one of the lead researchers. “But it is surprising is that it shows up for young girls. Conservative norms clearly apply to them too, along [with] parental concerns about their safety and security.”

Conservative values, increased monetary costs, concerns for safety—all of these reasons could discourage Pakistani parents from sending their daughters off to far away schools in unfamiliar neighborhoods. The graph offers reconciliation between what parents say in focus groups and what they do in action; they may value education for their daughters, but perceived societal cost of travel lowers willingness to enroll them.

Other research has shown the distance penalty at work in different countries and contexts. In Afghanistan, researchers showed that placing schools into villages raised enrollment for girls 17 percentage points more than for boys, suggesting that distance is a greater barrier for girls there. And another study in Pakistan found such effects to be most intense for girls of traditionally disadvantaged castes who would have to travel outside their caste enclave to attend schools, regardless of distance. That study showed that placing primary schools in low-caste hamlets increased enrollment twice as much as placing them in poor areas without taking caste composition into account.

The power of distance in limiting females from building human capital is not confined to girls. In a study on vocational training, Khwaja and co-authors tested a range of interventions to increase take-up of a government skills training program for young women in rural Punjab. While some of these programs, such as community support meetings and distribution of information, had no effect on women’s take-up of the training program, putting training centers in women’s villages raised it by 50%.

Exploring policy options

The government, however, has not taken these gender or cultural factors into account when trying to close the gender gap in primary enrollment. The school-merger policy in Punjab, for instance, merged low-enrollment schools with high-enrollment schools in the interest of utilizing material and human resources better. The merged schools may be at a greater distance for more girls, de-incentivizing attendance.

Other efforts have a better chance of addressing the distance penalty. Taking advantage of the unprecedented expansion of low-cost private schools in Pakistan, the government deployed an education voucher scheme program under the Punjab Education Foundation that allows disadvantaged children to be educated for free at a low-cost private school of their choice. With half a million children benefitting, this may be the largest education voucher scheme in the world. LEAPS research shows these modest schools outperform government schools, and the fact that they are small (often based in the owner’s homes) and widely dispersed could make them more accessible for girls.

Other features of low-cost private schools may make them Pakistan’s best chance for closing the gender gap. They primarily employ female teachers, which is reflected in the fact that they are three times more likely to emerge in villages that contain a government girls’ secondary school. Ironically, hiring female teachers is part of what keeps cost low (as women’s wages are lower than men’s) but still, the presence of women educators may be setting into motion a virtuous cycle of female empowerment that we have seen in other countries’ education systems.

Recently, the LEAPS team has received support from RISE, a large-scale education systems research program supported by the UK and Australian governments, allowing the team to further examine the teacher labor market and the barriers to improving learning outcomes in low-cost private schools. A growing store of data will expose finer gaps between the intent to educate and learning, and a new set of policies may help reduce the gender gap in primary enrollment in Pakistan.

Ravale Mohydin is a researcher at TRT World in Istanbul and a former LEAPS Program Manager at the Center for Economic Research in Pakistan (CERP), and Vestal McIntyre is a staff writer for Evidence for Policy Design (EPoD) at Harvard Kennedy School. The views are the opinions of the authors alone

This gender gap persists despite the government’s attempts to address it, such as stipend programs to incentivize parents to enroll girls and provincial laws to end gender segregation. These efforts aligned with Education for All (EFA), a global initiative that aimed, among other things, to eliminate gender disparity in primary and secondary education by 2015—a target Pakistan did not meet.

Curiously, the gap persists even as parents across Pakistan voice changing attitudes toward girls’ education. Surveys show more than 8 out of 10 Pakistanis say that education is equally important for boys and girls; very few say that it is more important for boys than girls or the other way round. One of us, Ravale, witnessed this close-up when she conducted focus group discussions with parents and teachers as program manager for Learning and Educational Achievement in Pakistan Schools (LEAPS), a long-running research initiative headed by Tahir Andrabi of Pomona College, Jishnu Das of the World Bank, and Asim I. Khwaja of Harvard Kennedy School and co-director of Evidence for Policy Design.

Surprisingly, most parents expected higher returns when it came to investing in a daughter's education as compared to a son's education, and several said that an education would arm girls to navigate social relations better, especially with in-laws

These focus groups, involving more than 200 parents and teachers of children enrolled in low-cost private schools in rural and urban northern Punjab in 2016, showed that many parents viewed girls’ schooling as a form of protection, and they expected social and financial clout for their daughters as a natural byproduct of education.

Surprisingly, most parents expected higher returns when it came to investing in a daughter’s education as compared to a son’s education, and several said that an education would arm girls to navigate social relations better, especially with in-laws.

The persisting gender gap in primary school enrollment could, then, be due to a misunderstood situation leading to misused funds. If society already shows greater acceptance of girls’ education, then government efforts to inform or incentivize parents may not be useful. On the other hand, if public schools either don’t exist or are too far away for girls to reach, it matters little whether their parents want their daughters to get educated.

The distance penalty

New research from the LEAPS project sheds light on this idea. Most Punjab households have a primary school within 500 meters, but girls’ enrollment plunges with distance while boys’ enrollment descends only slightly. For children who live right next to a school, there is almost no gender difference, but for children who live 100 meters away, a boy is more likely to attend school than a girl. The gap widens from there.

So the act of schooling itself is not at issue—what matters is the societal cost of travel. “You wouldn’t be as surprised to see this hold for adult women, given conservative norms about their mobility,” says Asim I. Khwaja, one of the lead researchers. “But it is surprising is that it shows up for young girls. Conservative norms clearly apply to them too, along [with] parental concerns about their safety and security.”

Conservative values, increased monetary costs, concerns for safety—all of these reasons could discourage Pakistani parents from sending their daughters off to far away schools in unfamiliar neighborhoods. The graph offers reconciliation between what parents say in focus groups and what they do in action; they may value education for their daughters, but perceived societal cost of travel lowers willingness to enroll them.

Other research has shown the distance penalty at work in different countries and contexts. In Afghanistan, researchers showed that placing schools into villages raised enrollment for girls 17 percentage points more than for boys, suggesting that distance is a greater barrier for girls there. And another study in Pakistan found such effects to be most intense for girls of traditionally disadvantaged castes who would have to travel outside their caste enclave to attend schools, regardless of distance. That study showed that placing primary schools in low-caste hamlets increased enrollment twice as much as placing them in poor areas without taking caste composition into account.

The power of distance in limiting females from building human capital is not confined to girls. In a study on vocational training, Khwaja and co-authors tested a range of interventions to increase take-up of a government skills training program for young women in rural Punjab. While some of these programs, such as community support meetings and distribution of information, had no effect on women’s take-up of the training program, putting training centers in women’s villages raised it by 50%.

Exploring policy options

The government, however, has not taken these gender or cultural factors into account when trying to close the gender gap in primary enrollment. The school-merger policy in Punjab, for instance, merged low-enrollment schools with high-enrollment schools in the interest of utilizing material and human resources better. The merged schools may be at a greater distance for more girls, de-incentivizing attendance.

Other efforts have a better chance of addressing the distance penalty. Taking advantage of the unprecedented expansion of low-cost private schools in Pakistan, the government deployed an education voucher scheme program under the Punjab Education Foundation that allows disadvantaged children to be educated for free at a low-cost private school of their choice. With half a million children benefitting, this may be the largest education voucher scheme in the world. LEAPS research shows these modest schools outperform government schools, and the fact that they are small (often based in the owner’s homes) and widely dispersed could make them more accessible for girls.

Other features of low-cost private schools may make them Pakistan’s best chance for closing the gender gap. They primarily employ female teachers, which is reflected in the fact that they are three times more likely to emerge in villages that contain a government girls’ secondary school. Ironically, hiring female teachers is part of what keeps cost low (as women’s wages are lower than men’s) but still, the presence of women educators may be setting into motion a virtuous cycle of female empowerment that we have seen in other countries’ education systems.

Recently, the LEAPS team has received support from RISE, a large-scale education systems research program supported by the UK and Australian governments, allowing the team to further examine the teacher labor market and the barriers to improving learning outcomes in low-cost private schools. A growing store of data will expose finer gaps between the intent to educate and learning, and a new set of policies may help reduce the gender gap in primary enrollment in Pakistan.

Ravale Mohydin is a researcher at TRT World in Istanbul and a former LEAPS Program Manager at the Center for Economic Research in Pakistan (CERP), and Vestal McIntyre is a staff writer for Evidence for Policy Design (EPoD) at Harvard Kennedy School. The views are the opinions of the authors alone