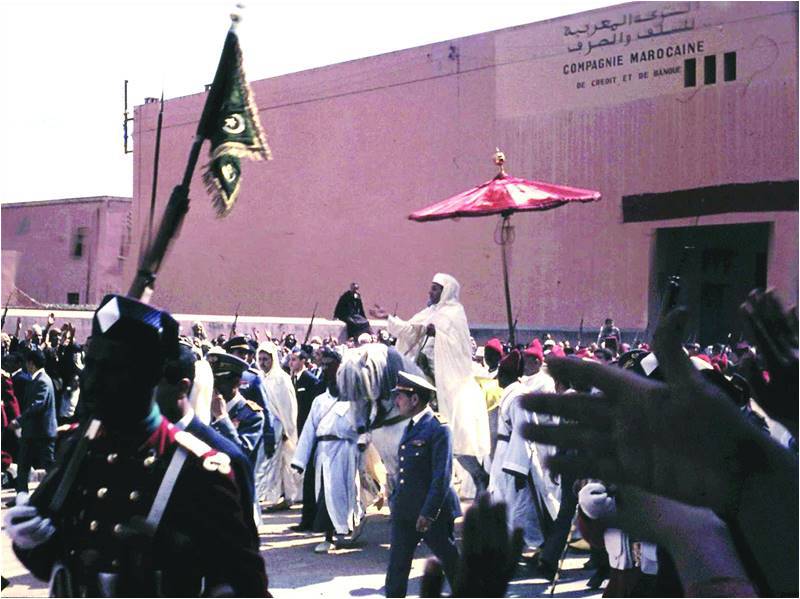

This photograph, captured in 1967, shows King Hassan II on his way to Friday prayers in Marrakesh. Hassan was the King of Morocco from 1961 until his death in 1999. He was known to be one of the most severe rulers of Morocco, widely accused of authoritarian practices and of being an autocrat and a dictator, particularly during the Years of Lead.

Hassan, after taking a law degree at Bordeaux, France, was appointed commander of the Royal Armed Forces (1955) and deputy premier (1960) and succeeded to the throne on the death of his father, Muḥammad V (1961). As king, Hassan tried to democratize the Moroccan political system by introducing a new constitution in 1962 that provided for a popularly elected legislature while maintaining a strong executive branch headed by the king. From 1965 to 1970 he exercised authoritarian rule in order to contain opposition to his regime, but he restored limited parliamentary government under a new constitution in 1970 and instituted some socioeconomic reforms following attempted coups in 1971, 1972, and 1973.

In the struggle between Morocco and Algeria over Spanish Sahara (later Western Sahara), Hassan strongly promoted Morocco’s claim to the territory, and in November 1975 he called for a Green March of 350,000 unarmed Moroccans into the territory to demonstrate popular support for its annexation. Western Sahara was in fact divided between Morocco and Mauritania, but this victory proved to be hollow, since guerrillas of the Polisario Front, agitating for Saharan independence, tied down Moroccan troops and prevented the exploitation of the phosphate deposits that had made the Sahara desirable to Morocco in the first place.

Despite criticisms concerning human rights abuses, Hassan was generally credited with having adroitly maintained the fragile unity of Morocco. He held on to his authority when several other Arab states were toppled by fundamentalist Islamic revolutionaries. In foreign affairs he cultivated markedly closer relations with the United States and the West than his father had. This closeness was to some extent possible because of Hassan’s moderate positions on the state of Israel. The United States especially valued his ability to mediate between conflicting parties in the Middle East. During World War II, Hassan’s father defied the Axis order to deport Morocco’s large Jewish population. Many Moroccan Jews immigrated to Israel after the war, and Hassan claimed that this population formed a bridge between Arabs and Israelis. By the early 1980s Hassan had accepted the existence of the state of Israel and moved to the forefront of peace negotiations in the Middle East.

Hassan, after taking a law degree at Bordeaux, France, was appointed commander of the Royal Armed Forces (1955) and deputy premier (1960) and succeeded to the throne on the death of his father, Muḥammad V (1961). As king, Hassan tried to democratize the Moroccan political system by introducing a new constitution in 1962 that provided for a popularly elected legislature while maintaining a strong executive branch headed by the king. From 1965 to 1970 he exercised authoritarian rule in order to contain opposition to his regime, but he restored limited parliamentary government under a new constitution in 1970 and instituted some socioeconomic reforms following attempted coups in 1971, 1972, and 1973.

In the struggle between Morocco and Algeria over Spanish Sahara (later Western Sahara), Hassan strongly promoted Morocco’s claim to the territory, and in November 1975 he called for a Green March of 350,000 unarmed Moroccans into the territory to demonstrate popular support for its annexation. Western Sahara was in fact divided between Morocco and Mauritania, but this victory proved to be hollow, since guerrillas of the Polisario Front, agitating for Saharan independence, tied down Moroccan troops and prevented the exploitation of the phosphate deposits that had made the Sahara desirable to Morocco in the first place.

Despite criticisms concerning human rights abuses, Hassan was generally credited with having adroitly maintained the fragile unity of Morocco. He held on to his authority when several other Arab states were toppled by fundamentalist Islamic revolutionaries. In foreign affairs he cultivated markedly closer relations with the United States and the West than his father had. This closeness was to some extent possible because of Hassan’s moderate positions on the state of Israel. The United States especially valued his ability to mediate between conflicting parties in the Middle East. During World War II, Hassan’s father defied the Axis order to deport Morocco’s large Jewish population. Many Moroccan Jews immigrated to Israel after the war, and Hassan claimed that this population formed a bridge between Arabs and Israelis. By the early 1980s Hassan had accepted the existence of the state of Israel and moved to the forefront of peace negotiations in the Middle East.