For a country with such a rich and millennia old heritage, we must be one of the world’s most careless and callous people with it. Anywhere else in the world, the riches of, for example the Lahore Museum, would’ve been beautifully and lovingly displayed, with huge crowds cleaving to its bosom day after day. Not a bit of it. The government has no money for our heritage. As a people, we’ve been brainwashed to believe that history begins with 1947, and a hop, skip and jump from events like the Arab invasion of Sindh in the 8th century, and a few other events in between, and that’s that. But Gandharans? Who? We? Never! Hindus? God forbid! Aryans? Perish the thought! So, it was both illuminating and a relief to take a break from these state-sponsored lies, and to visit a refreshing event which took place in Lahore recently.

A two-day festival, titled Heritage Now, organised at Alhamra Arts Center on The Mall in Lahore was a collaborative effort between the French Embassy in Pakistan, the British Council, the Walled City of Lahore Authority, the Higher Education Commission, UNESCO and Government of Pakistan National History and Literary Heritage Division.

Talking to The Friday Times, OIivier Huynh-van, counsellor for Cooperation and Cultural Affairs at the French Embassy, said, “We wanted to organise a cultural event which showcased the heritage of Pakistan. Naturally, UNESCO had to be involved in order for this event to be meaningful. The British Council also showed interest in organising such an activity and after a year’s effort, this event came together with many strong partners and sponsors.”

The festival brought together professionals from Pakistan and various other countries to discuss pressing issues facing museums and heritage sector in Pakistan through conservation, performance and art. It included panel discussions, presentation of academic papers, exhibitions, crafts and performances.

Alhamra was full to capacity on both days of the event. Hundreds of people, including academics, artists and professionals from various backgrounds, attended the festival. The center was festooned with artworks ranging from calligraphy and paintings to sculptures and handicrafts.

Rickshaws decorated in the traditional ‘truck art’ style could be spotted at various points of the venue. An open art studio had also been set up, inviting visitors to try their hand at various crafts. Scores of families were seen at these stations. A puppet show and a dhamaal was organised by Rafi Peer Theater at an outdoor stage.

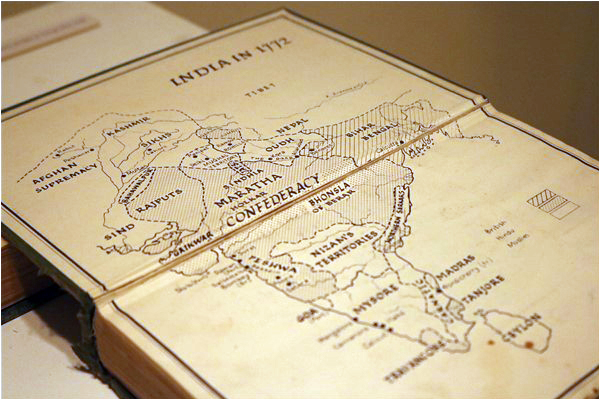

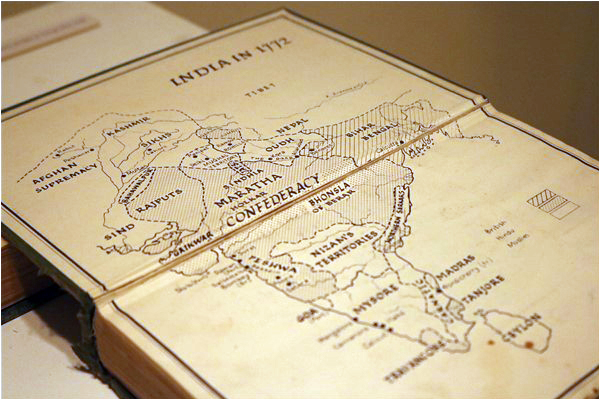

The British Council had set up a library featuring rare books written on historical events of the subcontinent. The Walled City of Lahore Authority had set up a Wekh Lahore photography exhibition. Students of National College of Arts showed their skill in terracotta sculptures by displaying some of their finest work. Replicas of renowned artefacts, such as the Dancing Girl of Mohenjodaro and Buddha statues, were also showcased at the event.

Addressing the audience, Punjab Governor Rafique Rajwana said, “I belong to the Seraiki belt which is a treasure trove of the ancient human footprint. Multan is full of heritage sites. Go down a 100 miles and you will find the ancient city of Uch Sharif. This place is known for its collection of shrines as old as the 12th century. These buildings are masterpieces of South Asian Islamic architecture”. The governor said Uch Sharif was also an important center in medieval India and was an early stronghold of the Delhi Sultanate.

Guimet Museum President Sophie Makariou told the audience that French archaeologists had been working in Pakistan since the 19th century. “Recently a team of archaeologists led by Aurore Didier completed an excavation at Chanhon Jo Daro in Sindh, a center of the Indus Valley civilization and found painted pottery, bangles, beads and a few terracotta objects. They seemed to be as old as the Indus valley civilisation”. She said the Guimet was founded in 1889 and had conducted several excavations in the Indus Valley in Balochistan. She urged Pakistani authorities to allow the exhibition of Buddha’s statue in the Lahore Museum, calling it mankind’s treasure.

Two-time Academy Award winner Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy premiered her first immersive exhibition at the event. Titled ‘HOME1947’, this unique exhibit featured stories of people who left their homes and migrated to Pakistan in 1947. Photographs, short documentaries and installations were displayed at the festival as part of the exhibit. This exhibit was an attempt by Obaid-Chinoy to depict the Partition through the eyes of those who had experienced it.

“This project is an ode to my grandparents’ generation whose stories I grew up listening to. As you walk through the installation, imagine the journeys of the people, their conversations, their friendships and promises, their playgrounds and suitcases of memories locked away forever,” Obaid-Chinoy said at the event.

Johannes Beltz from Museum Rietberg in Switzerland spoke on the importance of engaging communities with local museums. He said a child’s knowledge of the world could be expanded very easily through museums.

On museums, artist Salima Hashmi opened the discussion with a quote by Henry Ford who said, “Museums are like graveyards – full of dead things”. Hashmi added, quite wryly, “Those of us who live in Lahore understand this very well”. Talking of the silence of the graveyard, the promotion of Saudi religious ideology also came under fire at the event, during the panel discussion titled Diversity of Cultural and Religious Expression, with Sciences Po professor Christopher Jafferlot saying that it was pushing Muslims away from diversity and peaceful co-existence enshrined in their Sufi heritage.

“Pakistan’s Sufi heritage has remained under threat because of Arabisation which gained momentum during General Zia-ul-Haq’s dictatorship,” he said. Referring to the Mughal era, Jafferlot said most Mughal rulers had revered saints and opposed orthodox Muslims who equated Sufism with polytheism.

“Sufis brought together people from various religious and ethnic backgrounds and encouraged them to exist in harmony. This facilitated a culture which valued co-existence. Sufism defined the way of life of most people living under the Mughal rule until 1857,” he said. Sufism was also an essential part of Allama Iqbal’s philosophy, he maintained. “This influence came from themes in Shia Muslim history. This is evident in references to Karbala in Iqbal’s work.”

Jafferlot said Indian Muslim intellectuals were inclined towards the Ottoman Empire rather than the Saudis of Hijaz. “Muslims of the Subcontinent who participated in the Khilafat Movement were inclined towards the Ottoman model of diversity,” he said.

Ross Burns from Macquarie University spoke on group identity and how it developed through civilisations. He discussed Muslim emperors Nuruddin and Saladin who waged wars against the Fatimids because of religious differences. “These wars shaped the course of history in Muslim territories,” he said.

Finally, taking of heritage conservation, renowned architect Kamil Khan Mumtaz said, “Development for the sake of development is the psyche of a cancer cell. Humans should avoid such an attitude. We should first be very clear about what we want to develop and to what end”. Mumtaz says development should be understood as a process. “It is not a goal. We are in the midst of a global crisis (caused by this development paradigm) that is destroying our planet.”

Salimul Haq of the Department of Archaeology said the first law on monuments in the subcontinent was introduced by the British in 1904. He said the British divided local heritage in three categories. He said the conservation of monuments in the first category was their top priority. He said it was unfortunate that the British categories were retained after Independence in 1947. “We did not reevaluate our heritage. By the time Pakistan introduced its first law on heritage – the Antiquities Act 1975 – many monuments had already been lost to the ravages of time and plunder by locals who were unaware of their significance.”

In all, the seminar was a fascinating experience, both depressing and inspiring. We have lost a lot of our heritage because of our carelessness and our callousness. What remains needs to be conserved not only on the ground, but by educating minds on the importance of heritage, for who are we, without our past!

A two-day festival, titled Heritage Now, organised at Alhamra Arts Center on The Mall in Lahore was a collaborative effort between the French Embassy in Pakistan, the British Council, the Walled City of Lahore Authority, the Higher Education Commission, UNESCO and Government of Pakistan National History and Literary Heritage Division.

In all, the seminar was a fascinating experience, both depressing and inspiring

Talking to The Friday Times, OIivier Huynh-van, counsellor for Cooperation and Cultural Affairs at the French Embassy, said, “We wanted to organise a cultural event which showcased the heritage of Pakistan. Naturally, UNESCO had to be involved in order for this event to be meaningful. The British Council also showed interest in organising such an activity and after a year’s effort, this event came together with many strong partners and sponsors.”

The festival brought together professionals from Pakistan and various other countries to discuss pressing issues facing museums and heritage sector in Pakistan through conservation, performance and art. It included panel discussions, presentation of academic papers, exhibitions, crafts and performances.

Alhamra was full to capacity on both days of the event. Hundreds of people, including academics, artists and professionals from various backgrounds, attended the festival. The center was festooned with artworks ranging from calligraphy and paintings to sculptures and handicrafts.

Rickshaws decorated in the traditional ‘truck art’ style could be spotted at various points of the venue. An open art studio had also been set up, inviting visitors to try their hand at various crafts. Scores of families were seen at these stations. A puppet show and a dhamaal was organised by Rafi Peer Theater at an outdoor stage.

The British Council had set up a library featuring rare books written on historical events of the subcontinent. The Walled City of Lahore Authority had set up a Wekh Lahore photography exhibition. Students of National College of Arts showed their skill in terracotta sculptures by displaying some of their finest work. Replicas of renowned artefacts, such as the Dancing Girl of Mohenjodaro and Buddha statues, were also showcased at the event.

Addressing the audience, Punjab Governor Rafique Rajwana said, “I belong to the Seraiki belt which is a treasure trove of the ancient human footprint. Multan is full of heritage sites. Go down a 100 miles and you will find the ancient city of Uch Sharif. This place is known for its collection of shrines as old as the 12th century. These buildings are masterpieces of South Asian Islamic architecture”. The governor said Uch Sharif was also an important center in medieval India and was an early stronghold of the Delhi Sultanate.

Guimet Museum President Sophie Makariou told the audience that French archaeologists had been working in Pakistan since the 19th century. “Recently a team of archaeologists led by Aurore Didier completed an excavation at Chanhon Jo Daro in Sindh, a center of the Indus Valley civilization and found painted pottery, bangles, beads and a few terracotta objects. They seemed to be as old as the Indus valley civilisation”. She said the Guimet was founded in 1889 and had conducted several excavations in the Indus Valley in Balochistan. She urged Pakistani authorities to allow the exhibition of Buddha’s statue in the Lahore Museum, calling it mankind’s treasure.

Two-time Academy Award winner Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy premiered her first immersive exhibition at the event. Titled ‘HOME1947’, this unique exhibit featured stories of people who left their homes and migrated to Pakistan in 1947. Photographs, short documentaries and installations were displayed at the festival as part of the exhibit. This exhibit was an attempt by Obaid-Chinoy to depict the Partition through the eyes of those who had experienced it.

“This project is an ode to my grandparents’ generation whose stories I grew up listening to. As you walk through the installation, imagine the journeys of the people, their conversations, their friendships and promises, their playgrounds and suitcases of memories locked away forever,” Obaid-Chinoy said at the event.

Johannes Beltz from Museum Rietberg in Switzerland spoke on the importance of engaging communities with local museums. He said a child’s knowledge of the world could be expanded very easily through museums.

On museums, artist Salima Hashmi opened the discussion with a quote by Henry Ford who said, “Museums are like graveyards – full of dead things”. Hashmi added, quite wryly, “Those of us who live in Lahore understand this very well”. Talking of the silence of the graveyard, the promotion of Saudi religious ideology also came under fire at the event, during the panel discussion titled Diversity of Cultural and Religious Expression, with Sciences Po professor Christopher Jafferlot saying that it was pushing Muslims away from diversity and peaceful co-existence enshrined in their Sufi heritage.

“Pakistan’s Sufi heritage has remained under threat because of Arabisation which gained momentum during General Zia-ul-Haq’s dictatorship,” he said. Referring to the Mughal era, Jafferlot said most Mughal rulers had revered saints and opposed orthodox Muslims who equated Sufism with polytheism.

“Sufis brought together people from various religious and ethnic backgrounds and encouraged them to exist in harmony. This facilitated a culture which valued co-existence. Sufism defined the way of life of most people living under the Mughal rule until 1857,” he said. Sufism was also an essential part of Allama Iqbal’s philosophy, he maintained. “This influence came from themes in Shia Muslim history. This is evident in references to Karbala in Iqbal’s work.”

Jafferlot said Indian Muslim intellectuals were inclined towards the Ottoman Empire rather than the Saudis of Hijaz. “Muslims of the Subcontinent who participated in the Khilafat Movement were inclined towards the Ottoman model of diversity,” he said.

Ross Burns from Macquarie University spoke on group identity and how it developed through civilisations. He discussed Muslim emperors Nuruddin and Saladin who waged wars against the Fatimids because of religious differences. “These wars shaped the course of history in Muslim territories,” he said.

Finally, taking of heritage conservation, renowned architect Kamil Khan Mumtaz said, “Development for the sake of development is the psyche of a cancer cell. Humans should avoid such an attitude. We should first be very clear about what we want to develop and to what end”. Mumtaz says development should be understood as a process. “It is not a goal. We are in the midst of a global crisis (caused by this development paradigm) that is destroying our planet.”

Salimul Haq of the Department of Archaeology said the first law on monuments in the subcontinent was introduced by the British in 1904. He said the British divided local heritage in three categories. He said the conservation of monuments in the first category was their top priority. He said it was unfortunate that the British categories were retained after Independence in 1947. “We did not reevaluate our heritage. By the time Pakistan introduced its first law on heritage – the Antiquities Act 1975 – many monuments had already been lost to the ravages of time and plunder by locals who were unaware of their significance.”

In all, the seminar was a fascinating experience, both depressing and inspiring. We have lost a lot of our heritage because of our carelessness and our callousness. What remains needs to be conserved not only on the ground, but by educating minds on the importance of heritage, for who are we, without our past!