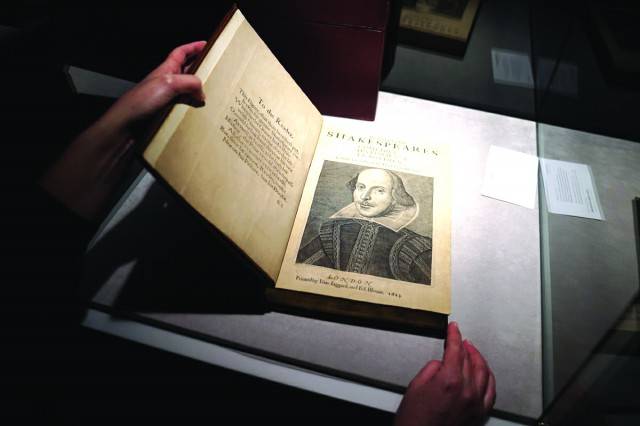

My father used to love taking us to a lovely bakery in Clifton to order our birthday cakes when we were children. I struggle to think of an occasion more thrilling than setting off to peruse pictures of cakes in all shapes and sizes and then select one to personalise. It was a treat like no other and the memory is entrenched in my mind. We did this on four occasions each year, which is intriguing given that I only have two siblings. The fourth cake was ordered on the eve of April 23rd and surpassed all other cakes in size and splendour. In all its enormity and deliciousness, it was dedicated to my father’s first love: Shakespeare. We grew up in a slightly surreal household where Shakespeare was talked about with an almost alarming familiarity. My siblings knew tragic soliloquys and would recite them verbatim to unsuspecting house visitors; my mother launched verbal attacks on the Bard’s works when she wanted to go for the jugular. My father resolved unprecedented results in cricket and politics with the disclaimer that “Some are born great, some achieve greatness and some have greatness thrust upon them.” He relegated many a political rogue to this last category.

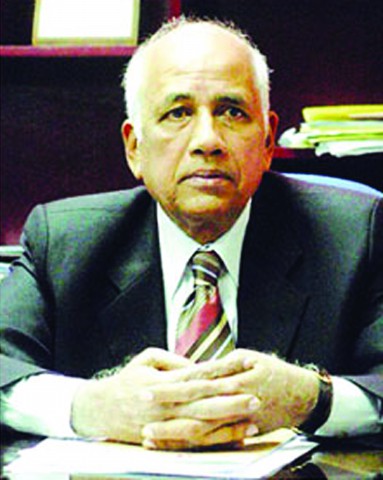

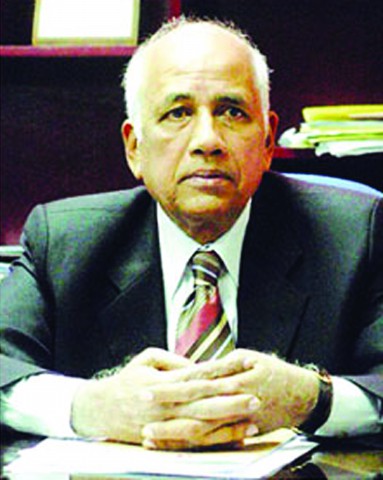

Professor Rafat Karim’s name became inextricably linked to Shakespeare in Pakistan in the 1990s and he became a pioneer for Shakespearean Studies in the country. In 1996, he organised what seemed nothing short of a miracle in the Karachi of those days: Pakistan’s first even International Shakespeare Conference attended by Shakespearean heavyweights from, quite literally, around the globe. The three-day affair was a sight to behold, drawing a motley crew of intellectuals, philistines and ‘indifferents’ from the city to come and listen to experts analyse Shakespeare’s work in astonishing detail. They left, in some cases, most profoundly confused. But never has confusion felt so delightful. The level and rigour of debate and argument felt exotic to my young mind; I remember my brain stretching itself to unprecedented limits to access the depth of scholarship and then the gratification that came from having taken something away. Something very small, but significant nonetheless. Something tangible and memorable.

My mother and siblings shared my father’s worry that people would be reluctant to return to the conference the next day, but they did – and in hoards. What was this magic that people couldn’t get enough of? The evening performances of the great tragedies were sell-outs on each night, with one man checking with my mum if meeting ‘Shakespeare Sahib’ would be a possibility on the night. We had tickets to sell, and my mum replied with a non-committal yet promising: “Inshallah” (God willing). I clearly remember tittering in the corner at my mother’s ability to casually give a man hope of encountering Shakespeare in person. I was also incredibly endeared at this entirely non-literary man’s keenness on meeting the Bard in the first place!

Even now, when I visit Pakistan and invariably run into a former student of my father’s, his influence on their lives has something powerful to do with Shakespeare. When my father passed away in 2008, my email inbox was thronged with messages of sorrow and condolence from Shakespearean scholars around the world. His students grieved for months to come, wanting to commemorate his contribution somehow, to make him indelible. Their messages quoted the great plays; they reminded me of the number of times my father had quoted “All that lives must die” and “We cannot hold mortality’s strong hand”. My father had made a difference. Many years later it has become clearer to me what my father was beginning to stir in the 1990s. My father was never elitist in his promotion of Shakespeare in Pakistan but rather determined that the Bard spoke to one and all, transcending time, age and culture. Like Nelson Mandela, who kept a copy of The Complete Works by his bedside for twenty years, he also believed that “Shakespeare always seems to have something to say to us.” There is immense reassurance and much catharsis to be sought in encountering the universal experiences of love and death, jealousy, and ambition isn’t there? I don’t know where I would be without it.

Hamlet famously begins with the line, “Who’s there?”. I have always loved Shakespeare’s incredible ability to complicate identity and fire curiosity. I am like a child spell-bound by the possibilities of “Who’s there?” My father and Shakespeare taught me to be very ponderous about that notion; about people, the stories they tell, the stories they don’t tell and the stories they can’t tell. This was my father’s gift to his family, to his students and his country. The 23rd of April is hence always poignant for me: to mark the lessons in life and love, learnt from Shakespeare, through my father.

Note: I am aware that the 23rd of April is highly debatable as Shakespeare’s birth date, but it’s what was marked in our home and has come to mean something to me. Believe it or not, my father chose his own birthday too!

The author received a PhD in English Literature from the University of Warwick and is an Associate Senior Leader at The Ridgeway Education Trust in Oxfordshire, England

Professor Rafat Karim’s name became inextricably linked to Shakespeare in Pakistan in the 1990s and he became a pioneer for Shakespearean Studies in the country. In 1996, he organised what seemed nothing short of a miracle in the Karachi of those days: Pakistan’s first even International Shakespeare Conference attended by Shakespearean heavyweights from, quite literally, around the globe. The three-day affair was a sight to behold, drawing a motley crew of intellectuals, philistines and ‘indifferents’ from the city to come and listen to experts analyse Shakespeare’s work in astonishing detail. They left, in some cases, most profoundly confused. But never has confusion felt so delightful. The level and rigour of debate and argument felt exotic to my young mind; I remember my brain stretching itself to unprecedented limits to access the depth of scholarship and then the gratification that came from having taken something away. Something very small, but significant nonetheless. Something tangible and memorable.

Many years later it has become clearer to me what my father was beginning to stir in the 1990s. My father was never elitist in his promotion of Shakespeare in Pakistan but rather determined that the Bard spoke to one and all, transcending time, age and culture

My mother and siblings shared my father’s worry that people would be reluctant to return to the conference the next day, but they did – and in hoards. What was this magic that people couldn’t get enough of? The evening performances of the great tragedies were sell-outs on each night, with one man checking with my mum if meeting ‘Shakespeare Sahib’ would be a possibility on the night. We had tickets to sell, and my mum replied with a non-committal yet promising: “Inshallah” (God willing). I clearly remember tittering in the corner at my mother’s ability to casually give a man hope of encountering Shakespeare in person. I was also incredibly endeared at this entirely non-literary man’s keenness on meeting the Bard in the first place!

Even now, when I visit Pakistan and invariably run into a former student of my father’s, his influence on their lives has something powerful to do with Shakespeare. When my father passed away in 2008, my email inbox was thronged with messages of sorrow and condolence from Shakespearean scholars around the world. His students grieved for months to come, wanting to commemorate his contribution somehow, to make him indelible. Their messages quoted the great plays; they reminded me of the number of times my father had quoted “All that lives must die” and “We cannot hold mortality’s strong hand”. My father had made a difference. Many years later it has become clearer to me what my father was beginning to stir in the 1990s. My father was never elitist in his promotion of Shakespeare in Pakistan but rather determined that the Bard spoke to one and all, transcending time, age and culture. Like Nelson Mandela, who kept a copy of The Complete Works by his bedside for twenty years, he also believed that “Shakespeare always seems to have something to say to us.” There is immense reassurance and much catharsis to be sought in encountering the universal experiences of love and death, jealousy, and ambition isn’t there? I don’t know where I would be without it.

Hamlet famously begins with the line, “Who’s there?”. I have always loved Shakespeare’s incredible ability to complicate identity and fire curiosity. I am like a child spell-bound by the possibilities of “Who’s there?” My father and Shakespeare taught me to be very ponderous about that notion; about people, the stories they tell, the stories they don’t tell and the stories they can’t tell. This was my father’s gift to his family, to his students and his country. The 23rd of April is hence always poignant for me: to mark the lessons in life and love, learnt from Shakespeare, through my father.

Note: I am aware that the 23rd of April is highly debatable as Shakespeare’s birth date, but it’s what was marked in our home and has come to mean something to me. Believe it or not, my father chose his own birthday too!

The author received a PhD in English Literature from the University of Warwick and is an Associate Senior Leader at The Ridgeway Education Trust in Oxfordshire, England