Given the big-ticket news developments, the details of the story unfolding in the South Caucasus have largely gone unnoticed.

In a precision military operation lasting little more than 24 hours, Azerbaijan has reshaped the map by retaking the Armenian-majority breakaway enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh. After the Azerbaijan military had first targeted and degraded the fighting positions of what was known as the Arstakh Republic, separatist Armenian militia fighters surrendered as the Azerbaijan military approached the outskirts of Stepanakert (called Khankendi by Baku).

Following the surrender, talks in Azerbaijan’s city of Yevlakh led to a decree last Thursday by Armenian separatist leader Samvel Shakhramanyan calling for the dissolution of “all state [unrecognised Republic] institutions and organisations under their departmental subordination by January 1, 2024, and the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh (Artsakh) ceases to exist.”

Source: BBC

Meanwhile in Armenia, Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan’s government is facing deep resentment and anger for not helping the erstwhile Arstakh Republic. Most observers believe that Pashinyan may not survive long in office.

How did this come about? That is the story of a methodical strategy adopted by Azerbaijan, a strategy that led its forces first in November 2020 to comprehensively defeat Armenia in a 44-day war and then to work towards liberating Nagorno-Karabakh.

Armenia and its military is in no position to deter the Azeri military or to defend Karabakh against an Azeri takeover. The growing differential between Azeri and Armenian economies and military capabilities is the main reason for Armenian defeats.

While the ethnic and territorial conflict dates back to the beginning of the 20th century, the present story began in 1988 when Armenia (then a Soviet Republic) demanded Nagorno-Karabakh from Azerbaijan (also a Soviet Republic). The conflict simmered with occasional clashes between the fighters of both former Soviet Republics until the demise of the Soviet Union on December 25, 1991.

The conflict that had begun during the glasnost period broke into a full-scale war between independent Azerbaijan and Armenia after the demise of the Soviet Union. Tens of thousands on both sides were killed by 1994. Armenia won that war. The Armenians in Karabakh established their breakaway republic while Armenia captured seven districts of Azerbaijan surrounding Karabakh, expelling thousands of Azeris in the process.

Fast forward to 2017, and intermittent clashes kept occurring between Azerbaijan and Armenia. Armenia, which had won the previous war rather comprehensively, did not realise that it had been falling behind Azerbaijan on multiple counts. The Azeri economy had been growing steadily (on the back of oil revenues, tourism, higher exports etc.) while the Armenian economy had been stagnating. Baku had the money to modernise its military and spend more on defence, despite spending a lesser percentage compared to Yerevan relative to GDP. For more details on that war see my article from November 20, 2020.

By September 2020, following some border clashes, Azerbaijan was ready to open hostilities. It began a well-planned and executed offensive on September 27, outsmarting the Armenian military by using surveillance and combat drones as well as loitering munitions. The surveillance drones also allowed it eyes in the sky for artillery engagements, both for strikes and counter battery operations. Azeri armed drones forced Armenia to hide its armoured and mechanised assets, while giving the Azeri military situational awareness of the war zone.

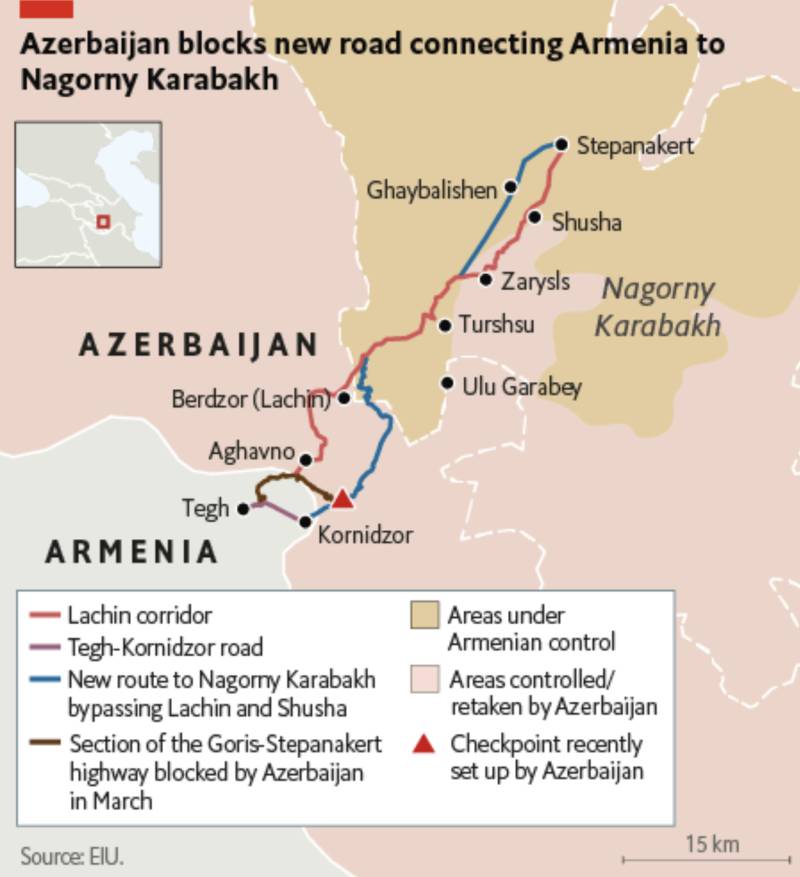

By the first week of November, Azerbaijan had retaken the seven districts lost to Armenia in 1994 and entrenched Azeri control of the Shusha district in southern Nagorno-Karabakh itself, which the Azeri army had captured in the final phase of the war. The capture of Shusha also meant Azeri control over the Lachin corridor, which became the only route linking Armenia with Nagorno-Karabakh. Under a Russian-brokered peace agreement, Azerbaijan also got land access through Armenian territory to Nakhchiven, its exclave abutting the border with Iran and a short, 17-km border on the northwestern tip with Turkey that runs along the Aras river.

Azerbaijan had successfully completed the first phase of its ultimate objective to make a final go for Nagorno-Karabakh. It had cleared the districts around Karabakh, had scored a huge operational and psychological advantage over Armenia and by controlling the only land corridor (Lachin) between Karabakh and Armenia — though it was to be monitored by Russian peacekeeping force — it could just blockade Karabakh Armenians and force them to accept Baku’s terms.

Two factors external to Azerbaijan’s strategy helped Baku immensely: deteriorating Russian-Armenian relations and Russia’s preoccupation with Ukraine since February 2022. Neither was Azerbaijan’s doing but both seem to have helped Baku.

With the Russo-Ukraine War dragging on, the Azeri military slowly diluted the mandate of Russian peacekeepers. The best example of that was their blockade of the Lachin corridor some nine months before the current operation. The Russians, once highly influential in the Caucasus, stood by while Azerbaijan set up a checkpoint in the corridor.

Armenia-Russia relations, already frayed despite Russia being a security guarantor for Yerevan, deteriorated further when Azerbaijan set up the checkpoint without any resistance from Russian peacekeepers. Russia was also angered by Armenia’s joint military exercise with US troops. To top that, Armenia sent humanitarian aid to Ukraine for the first time in early September and it was delivered by Pashinyan’s wife, Anna Hakobyan. Hakobyan was on an official visit to Kyiv.

“We are not Russia’s ally in the war with Ukraine,” Pashinyan told CNN Prima News in an interview in June. “And our feeling from that war, from that conflict, is anxiety because it directly affects all our relationships.”

For the conflict to really end, Baku will have to show empathy and generosity. There is some sense that Azerbaijan and Turkey might open their borders to Armenia as a quid pro quo to a land corridor between Ankara and Baku going through Armenia. If amicably settled, the corridor could become the basis for normalisation.

According to another CNN report, Pashinyan criticised Russia for not alerting him to Azerbaijan’s military plans, saying it was “strange and perplexing” that his government did not receive “any information from our partners in Russia about that operation.” For their part, senior Kremlin leaders, notably former Russian President, Dmitry Medvedev, bitterly criticised Pashniyan. Medvedev wrote in a Telegram post: “He [Pashniyan] lost a war [the 2020 conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia] but in some strange way stayed in place. Then he decided to shift the responsibility for his talentless defeat onto Russia. Then he rejected a piece of the territory of his own country. Then he decided to flirt with NATO. Guess what fate awaits him.”

The fact is, Pashinyan’s criticism of Russia notwithstanding, Armenia and its military is in no position to deter the Azeri military or to defend Karabakh against an Azeri takeover. The growing differential between Azeri and Armenian economies and military capabilities is the main reason for Armenian defeats. During the Soviet era, Armenia had developed a fairly robust industrial base, manufacturing machine tools. It also had a thriving textile sector. After the Soviet breakup, Armenia shifted to small-scale agriculture and some tourism. The conflict with Azerbaijan also deprived it of land routes east through Azerbaijan and west through Turkey. Its only openings now are towards Iran and Georgia.

Source: Economist Intelligence Unit

However, while Azerbaijan has won back its territories and weakened its adversary, for the conflict to fully end would now largely depend on what Baku does here on out. It has talked for long about the reintegration of any Armenian population, especially in Nagorno-Karabakh. But reintegration is not that easy to pull off, especially given the long and bloody history of conflict between ethnic Azeris and Armenians. One of the reasons the Armenian Soviet Republic had demanded the return of Karabakh was because of Azeri excesses against Armenians. Armenia did the same when they captured seven Azeri districts and Karabakh in the early 90s, killing and expelling Azeris.

For the conflict to really end, Baku will have to show empathy and generosity. There is some sense that Azerbaijan and Turkey might open their borders to Armenia as a quid pro quo to a land corridor between Ankara and Baku going through Armenia. If amicably settled, the corridor could become the basis for normalisation.

If, however, as Armenia fears, Azerbaijan tries to forcibly control the Zangezur corridor that runs the entire southern length of the Azerbaijan-Iran and Armenia-Iran borders before turning northwest in Nakhichevan, the Azeri exclave, the situation could become conflictual not just because of Yerevan but also Tehran, which does not oppose the trade and travel corridor per se, but not if it results in a portion of Armenia’s southern Syunik province being separated from the control of Armenia in the form of a special legal regime.

In other words, while “Iran has not allowed Nakhchivan’s connection with the mainland to be cut off, permitting the citizens of Azerbaijan to travel through Iran,” it would not want Azeri control of Syunik. It may be that Azerbaijan could forcibly do it, given the current capabilities differential, but that would amount to an aggression that could sow the seeds of more conflict in the years to come.