The current global crisis is a combination of three symbiotic crises: a health issue, an economic shock and political failure. In many ways, rather than throwing something new at us, the Coronavirus crisis has accelerated trends already in place, whether it is growing inequality, a crumbling global order, weak social services, etc. This is forcing many, although not nearly enough, to rethink our socioeconomic structures in hopes of avoiding a total capitulation of the system. One of the leading ideas picking up steam around the world is that of a Job Guarantee program, two examples of which from developing countries are Argentina and India.

Pavlina Tcherneva lays this idea out in her new book The Case for a Job Guarantee, in which she argues that the government should act as the employer of last resort because the private sector will never be able to create enough jobs to lead to full employment. Mainstream economists often believe there is a “natural rate of unemployment” beyond which there is the threat of uncontrolled inflation. This framing of macroeconomic policy justifies, even in the most aspirational state, an economy with millions unemployed based on a hypothesis with limited evidence. Marx called this the “reserve army of labour” and critiqued it as a way of cheapening the value of labour for exploitation.

Unemployment as an economic and social ill at the individual and collective level is a well-documented fact. Substantial evidence exists that ties unemployment to poverty, mental health, social discord, abuse, etc. Why then does the government not take the lead in fighting unemployment, not by displacing the private sector but by creating a public option for jobs, such that anyone who wants to work but cannot find work in the private sector is offered temporary employment in the public sector? Before people start thinking this is some Soviet style state expansion, the difference is in employer of first resort (Soviet model) versus last resort (JG program) approach.

The big question is how the state can financially afford this. Here it is essential to introduce the economic framework that underpins the JG – Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). This approach is perhaps the hottest topic in economics globally today, prompted by public support from US Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio Cortez, and a recently published bestseller The Deficit Myth by Stephanie Ketlon, former chief economist for Bernie Sanders.

MMT dispels the conventional myth believed by economists and citizens that the government budget is like that of a household, hence it must balance its income (taxes) and expenditure (spending). If it spends more than it receives – budget deficit – it adds to its debt which will have to be paid by future generations. This is refuted by MMT which shows, through macroeconomic analysis, anthropology, and legal analysis, that governments always finance spending through money creation through their monopoly power, and then tax back a portion of it for reasons other than financing expenditure. Without the government first spending money into existence, the private sector would not have money to pay taxes with.

There are two constraints on government spending: inflation and limited real (non-financial) resources. Governments can afford to spend on education, healthcare, and other public services as long as this spending is utilising previously unused resources or improving productivity. This is over-simplified for the sake of brevity – Kelton’s and Tcherneva’s books, among many others, provide a lucid and intuitive description of this.

Only governments with monetary sovereignty have this luxury though: those that issue their own currency, do not have a fixed exchange rate, tax in their own currency, and do not borrow in foreign currency. Pakistan does not fully check all boxes and hence the implications are complicated, but the principle still holds. The main challenges are foreign debt which cannot be financed through domestic printing, and the reliance on imports which puts pressure on the exchange rate. For Pakistan to enjoy the benefits of a monetarily sovereign state, it needs structural adjustment that, unlike the stale IMF programs that force the country to dig its hole deeper, targets self-sufficiency in sectors of the economy reliant on imports to ease the need for foreign debt.

How does this tie to the JG program? Pakistan’s unemployed labour is an example of underutilised resources that can be used to enhance the productivity of the economy. Therefore, as the government creates more jobs, it is expanding the output of the economy while putting resources in the hands of those that most need them. It can also target these jobs in key sectors such as agriculture, energy, and infrastructure to reduce foreign exchange spent on imports, fight against climate change, and provide public services.

There are four additional benefits. It is a counter-cyclical policy because when times are bad, as they are now, private sector contractions can be somewhat offset by government spending expansion, as those laid off from private employment can be employed by the JG.

Second, it creates a minimum requirement of what employment should look like by providing a living minimum wage and decent working conditions, which the private sector is forced to compete with. Given Pakistan’s weak regulatory control over the private sector, this might be a better way to improve labour conditions.

Third, the JG can be used as training or (re)skilling program so workers are better equipped for private sector employment.

Lastly, there are substantial social benefits to employment, such as improved self-worth, increased civic engagement, reduced violence, better mental health, etc.

The two most relevant examples are Argentina and India. The former is also a notoriously debt-ridden country, once a poster boy for IMF policies but now negotiating out of a second debt default. Its JG program Plan Jefes in 2001, right after its first default and in the midst of a deep recession, employed 13 percent of the labour force, and pushed the economy towards recovery.

In India, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee (MGNREG) has provided a safety net to rural-urban migrants that have been forced back to their villages by the pandemic, and has helped created rural infrastructure over the past few years. Both these countries opted for restricted JG programs, where only one member per household was given employment for a specific number of days a year – and only in rural areas in India.

Pakistan should consider following a similar approach given the influx of migrant labour as the global economy contracts, increasing layoffs in the domestic private sector, and a growing young labour force. IMF structural adjustments are only pushing the spiral deeper, as they always have, and the narrative of export led growth will only lead to more foreign debt. And while progressive voices have been calling for a universal basic income, a JG would be more viable as tackles a broader variety of issues than just providing money to those in need.

This is not a justification for an already inflated public sector and bureaucracy; rather it highlights the role of government in directly boosting the economy through spending on productive endeavours and not being tied down by the balanced government budget myth. A JG program will help fight the structural issues to make the country more monetarily sovereign in the long run, while providing a social safety net and investment boost in the short run.

Pavlina Tcherneva lays this idea out in her new book The Case for a Job Guarantee, in which she argues that the government should act as the employer of last resort because the private sector will never be able to create enough jobs to lead to full employment. Mainstream economists often believe there is a “natural rate of unemployment” beyond which there is the threat of uncontrolled inflation. This framing of macroeconomic policy justifies, even in the most aspirational state, an economy with millions unemployed based on a hypothesis with limited evidence. Marx called this the “reserve army of labour” and critiqued it as a way of cheapening the value of labour for exploitation.

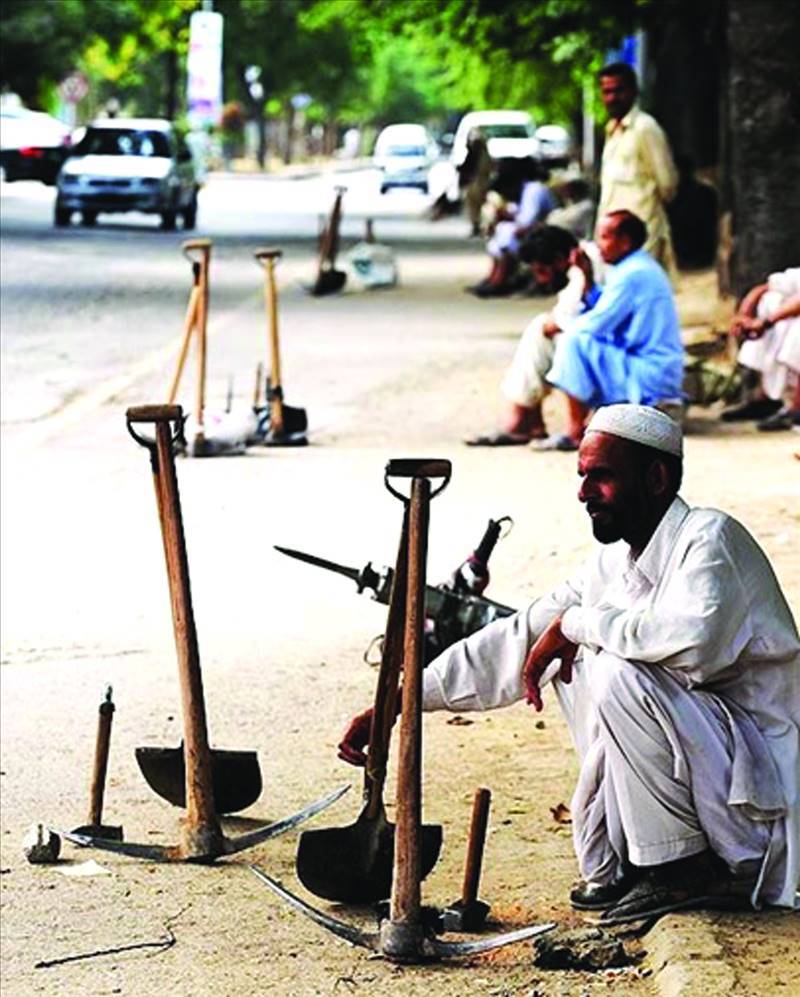

Pakistan’s unemployed labour is an example of underutilised resources that can be used to enhance the productivity of the economy

Unemployment as an economic and social ill at the individual and collective level is a well-documented fact. Substantial evidence exists that ties unemployment to poverty, mental health, social discord, abuse, etc. Why then does the government not take the lead in fighting unemployment, not by displacing the private sector but by creating a public option for jobs, such that anyone who wants to work but cannot find work in the private sector is offered temporary employment in the public sector? Before people start thinking this is some Soviet style state expansion, the difference is in employer of first resort (Soviet model) versus last resort (JG program) approach.

The big question is how the state can financially afford this. Here it is essential to introduce the economic framework that underpins the JG – Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). This approach is perhaps the hottest topic in economics globally today, prompted by public support from US Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio Cortez, and a recently published bestseller The Deficit Myth by Stephanie Ketlon, former chief economist for Bernie Sanders.

MMT dispels the conventional myth believed by economists and citizens that the government budget is like that of a household, hence it must balance its income (taxes) and expenditure (spending). If it spends more than it receives – budget deficit – it adds to its debt which will have to be paid by future generations. This is refuted by MMT which shows, through macroeconomic analysis, anthropology, and legal analysis, that governments always finance spending through money creation through their monopoly power, and then tax back a portion of it for reasons other than financing expenditure. Without the government first spending money into existence, the private sector would not have money to pay taxes with.

There are two constraints on government spending: inflation and limited real (non-financial) resources. Governments can afford to spend on education, healthcare, and other public services as long as this spending is utilising previously unused resources or improving productivity. This is over-simplified for the sake of brevity – Kelton’s and Tcherneva’s books, among many others, provide a lucid and intuitive description of this.

Only governments with monetary sovereignty have this luxury though: those that issue their own currency, do not have a fixed exchange rate, tax in their own currency, and do not borrow in foreign currency. Pakistan does not fully check all boxes and hence the implications are complicated, but the principle still holds. The main challenges are foreign debt which cannot be financed through domestic printing, and the reliance on imports which puts pressure on the exchange rate. For Pakistan to enjoy the benefits of a monetarily sovereign state, it needs structural adjustment that, unlike the stale IMF programs that force the country to dig its hole deeper, targets self-sufficiency in sectors of the economy reliant on imports to ease the need for foreign debt.

How does this tie to the JG program? Pakistan’s unemployed labour is an example of underutilised resources that can be used to enhance the productivity of the economy. Therefore, as the government creates more jobs, it is expanding the output of the economy while putting resources in the hands of those that most need them. It can also target these jobs in key sectors such as agriculture, energy, and infrastructure to reduce foreign exchange spent on imports, fight against climate change, and provide public services.

There are four additional benefits. It is a counter-cyclical policy because when times are bad, as they are now, private sector contractions can be somewhat offset by government spending expansion, as those laid off from private employment can be employed by the JG.

Second, it creates a minimum requirement of what employment should look like by providing a living minimum wage and decent working conditions, which the private sector is forced to compete with. Given Pakistan’s weak regulatory control over the private sector, this might be a better way to improve labour conditions.

Third, the JG can be used as training or (re)skilling program so workers are better equipped for private sector employment.

Lastly, there are substantial social benefits to employment, such as improved self-worth, increased civic engagement, reduced violence, better mental health, etc.

The two most relevant examples are Argentina and India. The former is also a notoriously debt-ridden country, once a poster boy for IMF policies but now negotiating out of a second debt default. Its JG program Plan Jefes in 2001, right after its first default and in the midst of a deep recession, employed 13 percent of the labour force, and pushed the economy towards recovery.

In India, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee (MGNREG) has provided a safety net to rural-urban migrants that have been forced back to their villages by the pandemic, and has helped created rural infrastructure over the past few years. Both these countries opted for restricted JG programs, where only one member per household was given employment for a specific number of days a year – and only in rural areas in India.

Pakistan should consider following a similar approach given the influx of migrant labour as the global economy contracts, increasing layoffs in the domestic private sector, and a growing young labour force. IMF structural adjustments are only pushing the spiral deeper, as they always have, and the narrative of export led growth will only lead to more foreign debt. And while progressive voices have been calling for a universal basic income, a JG would be more viable as tackles a broader variety of issues than just providing money to those in need.

This is not a justification for an already inflated public sector and bureaucracy; rather it highlights the role of government in directly boosting the economy through spending on productive endeavours and not being tied down by the balanced government budget myth. A JG program will help fight the structural issues to make the country more monetarily sovereign in the long run, while providing a social safety net and investment boost in the short run.