“They are extremely delicate in their person, soft and regular in their features, with a form of perfect symmetry, and although dedicated from infancy to this profession, they in general preserve a decency and modesty in their demeanor, which is more likely to allure than the shameless effrontery of similar characters in other countries.”

James Forbes (1749–1819)

Oriental Memoirs (1813)

A lot has been written, and said, about the Indian nautch girl. She has featured prominently in histories, novels, short stories, paintings, photographs, memoirs and travelogues. Yet little has been said about her unique and distinct identity among the women whose primary occupation is to indulge, entertain and woo men.

A nautch girl is not a Domni, Kasbi, Randi, Tawaif, Kanjari, Nochi or Devdasi; she belongs to her own distinctive class.

A domni makes her living by singing for both men and women, and belongs to a family of singers that has been in the profession for several generations. A kasbi is a prostitute belonging to a family where women have practiced the sex trade for generations. A randi is also a prostitute but one who does not belong to a family of sex workers. The kasbi is considered to be of a higher class than the randi. The tawaif, or more correctly a gharanedar tawaaif, belongs to a family of the highest class of courtesans. She caters, almost exclusively, to nobility, senior officers of the Raj, and the elite. The tawaif is a master of the arts – singing, dancing, acting, poetry recitation and composition, literature and cooking. She is erudite, well-read, often multi-lingual, and an authority on decorum and etiquette. A kanjari is a low-class tawaif with little to no education and no formal training in the arts. She does not come from a family of tawaaifs and, therefore, does not command the respect accorded to gharanedar courtesans. Her clients are the nouveaux riche and men from castes that include shaikhs (tradesman), gujjar (herdsmen), jats (landowners) and qazis (officers and bureaucrats). The word tawaaif has clout and commands respect whereas kanjari is used mostly as a derogatory term. A nochi is a young girl under the training of a tawaaif. She is expected to be a virgin. A devdasi devotes her entire life to the worship and service of an idol, deity or temple. She is not allowed to marry and is almost always subjected to sexual abuse.

The nautch girl is different.

A nautch girl is primarily a dancer and entertains men, women and children, in their homes, in public places, on stage and in various other settings. The word ‘nautch’ is the anglicized version of the Urdu and Hindi word for dance – naach. A nautch girl is one who dances to make a living.

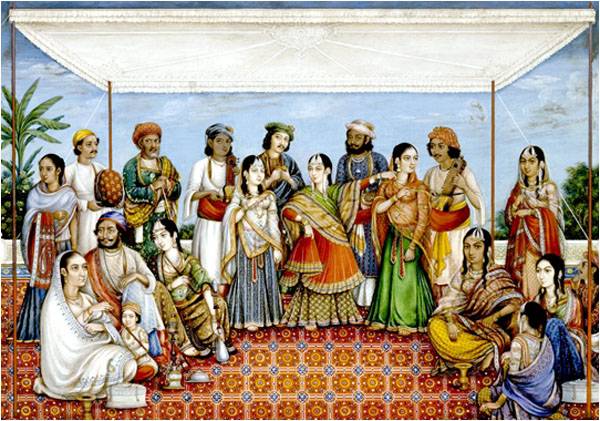

Nautch girls were a prominent part of Indian life and culture during the second half of the 19th and first half of the 20th centuries. Nautch girls danced for a variety of people that included women and children in addition to men of virtually all social classes. They performed in Mughal courts, the palaces of nawabs, the mahals (castles) of rajas, the bungalows of officers of the British Raj, the homes of nobles, the havelis (mansions) of zamindars (landowners) and many other places. They were invited to perform at parties, weddings, christenings, religious ceremonies, and many other social occasions. Nautch girls did not need an invitation to perform at religious festivals. They would show up to perform at the homes of their wealthier patrons who were obliged to pay them. While travelling from one city to another, they would often hold impromptu dance performances on roads, streets and thoroughfares to entertain the masses, make some money and secure free room and board. Nautch girls served the entire spectrum of people in India, across all regions, social classes, castes and religions.

[quote]Their husbands usually worked as musicians in the troupe[/quote]

Nautch girls performed as a part of small troupes known as the nautch parties. A typical nautch party consisted of ten to twelve people but could be as small as one with just two people. The party always had one or two dancers and usually a singer too. Their husbands usually worked as musicians in the troupe. The nautch party musicians played four instruments – sarangi, tabla, manjeera and dholak, historically. A fifth instrument – the harmonium – was introduced to nautch, primarily in Kashmir and Punjab, at the start of the 20th century. Well-known and famous nautch girls, however, looked down upon the harmonium and continued to use the sarangi. An experienced maidservant, the mama, was always a part of the nautch party. The mama was responsible for taking care of the female performers, arranging meals, and the safekeeping of the jewelry worn by the nautch girls. An unarmed guard, the muhafiz, was an important member of the nautch party given the turbulent times and political upheavals of 19th and 20th century India. His job was to protect all members and possessions of the nautch party. Nautch parties that performed during the night also had one or two mashalchis, or lamp bearers, in the troupe.

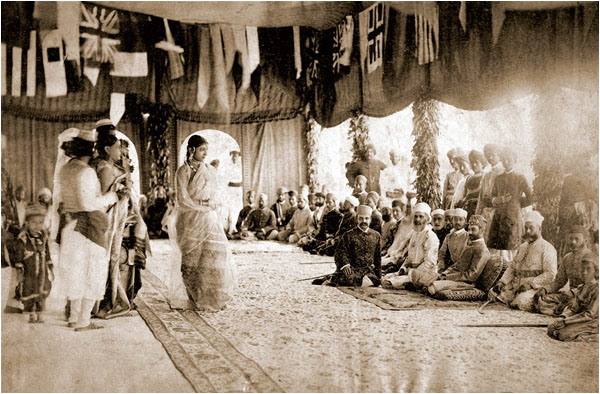

“The tent was most glaringly lighted, massaulchis or torch-bearers stood here and there ready to attend to any person who might require them...we had scarcely seated ourselves ere two of them made their appearance, floating into our presence, all tinsel colored muslin and ornaments: they were followed by three musicians, and attended by a couple of mussaulchis who held their torches first to the face and then lower down as if showing off the charms of the dancers to the best advantage.”

Lieutenant Thomas Bacon

Description of Late Evening Nautch

The dances performed by the nautch girls were simple. They did not follow any one classical style but borrowed liberally from three dance traditions – kathak, dasi attam and folk. The kathak of early nineteenth century was simple. The repertoire of toras and tukras was limited, and primary focus was on storytelling. Kathak had not yet been transformed into an elaborate school of dance by Bindadin Maharaj and Kalka Prasad Maharaj. It was aesthetically pleasing and elegant but not intricate and complex. Dasi Attam, the primitive form of Bharat Natyam, was more complex but lent itself easily to use in the popular dance of nautch girls. Folk dances added a charming and local flavor to the nautch. It was up to the nautch girls to masterfully incorporate elements of all three styles of dance into their performances.

The mor ka nach (dance of the peacock), patang nach (the kite dance) and the qahar ka nach (the bearer’s dance) were considered essential items in every nautch girl’s repertoire.

[quote]The mor ka nach was performed only for men[/quote]

In the mor ka nach, the dancer played the role of a peacock trying to attract peahens. An intensely erotic dance, it was performed only for men. Key features of this dance were short hops followed by breezy pirouettes where the dancer spreads her ghagra, or long skirt, to represent the spread fathers of the peacock. The ghagra was made in an iridescent peacock color and sometimes adorned with actual peacock feathers. In real life, peahens pick their mates based on color, feather quality and size. Similarly, the quality of the dance was judged on the basis of the quality of the ghagra, the grace of the dancer and the extent to which she could increase her size by spreading the ghagra. Elements of eroticism were added to the dance by the suggestive use of the dancer’s bosom, carefully studied displays of legs when spreading the ghagra, and a provocative locking of the eyes with the audience.

In the patang nach, the dancer imitated both the kite and the person who flew the kite. The nautch girl danced to depict the graceful ascent of the kite, the tussle of the kite when engaged with another, and its slow descent after the dor or string had been cut. The gestures, energy and emotions of the kite flyer were mimicked in the dance. The patang nach was performed at slow tempo, emphasizing grace, elegance and poise. The dance was sometimes performed by a duo of dancers, where one played the role of the kite and the other represented the person flying the kite.

The qahar ka nach was performed only for men and, though more subtle than the mor ka nach, was decidedly erotic in nature. The dancer used silk sashes, the ghagra and her own long tresses as props while she performed the exaggerated and animated moves that characterized the qahar ka nach. The dance was performed in close proximity to the audience. The nautch girl teased a favored few amongst the audience by slowly advancing towards them, in a manner suggestive of an imminent kiss, and retreating at the last moment. The dance was usually the finale of a nautch performance.

[quote]Nautch girls were photographed extensively in the late 19th and early 20th centuries[/quote]

Nautch girls used the lighter genres of classical music – thumri, dadra, ghazal and geet – in their performances. In courts, palaces, bungalows and the homes of the rich and the privileged, musicians would always play their instruments while standing. In public performances, and in more austere settings, they sat down on the floor to perform. The muhafiz stood to one side and kept an eye on everyone present during the performance. Mamas sat in a corner of the dais, sometimes preparing paan (betel nut) and beeri (Indian cigarettes). Mashalchis stood at the back

Nautch girls were photographed extensively in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Three factors contributed to this trend. The first was the ever-increasing popularity of the camera, which was introduced in India around 1840. The second was the desire to record the vast diversity of Indian people along with their clothing, vocations, manners, crafts, customs, practices, and religions. Nautch girls were an ideal subject for photographers wishing to document Indian culture. They were beautiful, native, willing to be photographed and represented a unique slice of the country’s culture. The third factor was a nautch girl’s need to have good photographs that she could send to prospective clients. The quality of the photograph was directly tied to the price a nautch girl commanded. Great efforts were made to take flattering photographs of nautch girls in studios. Nicholas & Curths, Hooper and Western, Charles Shepherd, Samuel Bourne, and Francis Frith were the photographers of choice for nautch girls who could afford to pay their relatively high fees. The best photographs were set in wood frames that were decorated with marquetry, ivory, brass and intricate carving. The frames were wrapped in chenille fabric for safekeeping. They were carried to the homes of prospects by the muhafizes who initiated commercial discussions related to nautch performances. The photographs were not used for display and decoration.

Nothing can exceed the transcendent beauty, both in form and lineament, of [the nautch girls].

William Daniell & Hobart Caunter

Scenes in India (1835)

The popularity of the nautch was at its peak in the 1860s; a natural consequence of the popularity was the emergence of detractors of the art form. Waves of Christian missionaries started arriving in India after the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. These missionaries frequently opposed the performance of nautch, among many other things, by terming it anti-Christian, immoral and repugnant. Officers of the British Raj, who had heretofore been patrons of nautch girls, were asked to not attend nautch performances. (And it has been argued that after the “Mutiny” of 1857, the British were anyway disinclined to mix with the natives, now preferring to emphasize their superiority to their subjects.)

Though it acquired pejorative associations in the early 20th century, the tradition of nautch survived the onslaught of the moral brigade and went on to thrive in the Indian subcontinent.

Ally Adnan lives in Dallas, Texas, where he works in the field of mobile telecommunications and writes about culture and art. He can be reached at allyadnan@outlook.com