It is a surprise to many that Urdu, the lingua franca of Pakistan, is a minority language spoken by only 8% of the country's population - bearing the often misconstrued entitlement of the country's “native” tongue. Meanwhile, India - its true birthplace - is home to more than 70 million speakers of Urdu, where the language was first conceived - as few dare to acknowledge - in the stately courts of Delhi and Lucknow.

Despite these facts, most people on either side of the border continue to perceive the other's culture and language as diametrically opposed to their own: “Urdu is the language of Pakistan”, they're told, “and Hindi that of India”. This is believed although both languages are mutually intelligible and were essentially two sisters born of the same parent language. When, then, did one begin to be associated with Islam, and the other with Hinduism? And how, despite their closeness, could such minuscule differences between them lead to the creation of two separate countries?

The bifurcation of Hindi and Urdu was a deliberate process that takes its roots in a series of events that progressed from trivial flourishes of vocabulary to religious purges and ultimately nationalistic attributions. It is also one that tragically illustrates what results when the supple nature of a language is manipulated to fit the needs of a certain social group that seeks to distinguish itself from another on the grounds of religious intolerance.

The development of Urdu

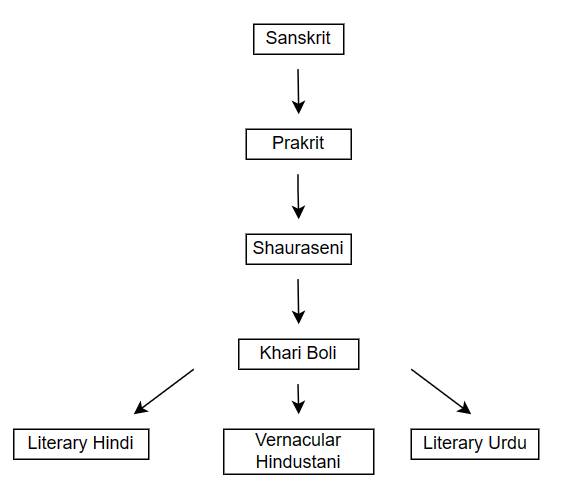

Urdu and Hindi take their roots in a common ancestor by the name of Khari Boli - a Middle Indo-Aryan vernacular language originating from the Gangetic Doab that was widely used in the localities of Northern India. Following Mahmud Ghaznawi's annexation of Punjab in 1027 and Qutb ud Din Aibak's establishment of the Delhi Sultanate in 1206, the language (presumably Persian) of the troops stationed in Lahore and later Delhi merged with the Khari Boli of the locals in the bazaars, while Persian remained being spoken in the courts.

Through this process, the Khari dialect gradually fell out of use as a new language came into being which shared many of the former’s grammatical and phonetic features (given that the locals heavily outnumbered the soldiers). Later, Muhammad Tuglaq's invasion of the Deccan in 1346 brought the same concocted language to Southern India, where it came to be known as Deccani.

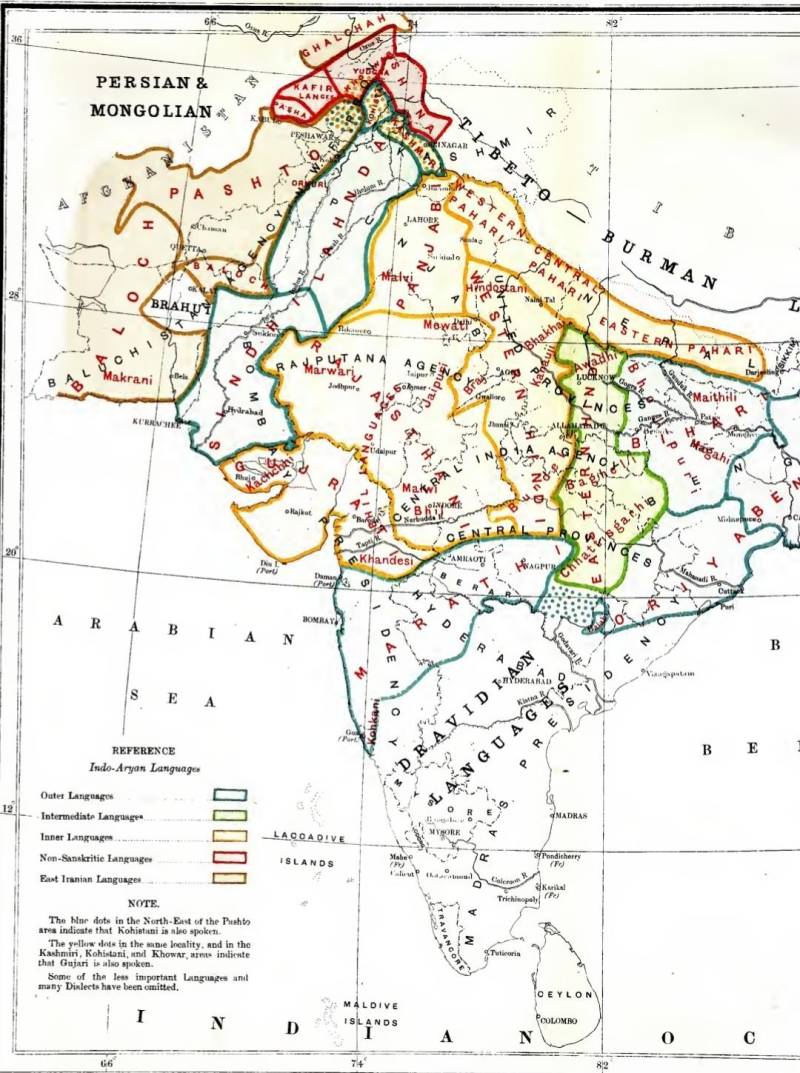

At this period, it would be misleading to refer to the language as "Urdu", since the term only began to be used as late as 1750. Before then, the language was known by a range of ambiguous designations as varied as Delhavi, Rekhta, and - as Khusro called it - Hindavi. Furthermore, the word “Hindi” did not yet refer to Hindi as we know it today (i.e: Sanskritized Hindi using the Devanagari script) but was a fluid term that denoted the language commonly understood across most of India, from the the Upper Doab in the North all the way to the Deccan in the South, indicating “all the rural dialects spoken between Bengali Proper and the Punjab”.

The language that grew around the armies stationed in Delhi, as their Persian speech mingled with the local dialect of Khari Boli, soon began to spread as Mughal influence grew across India. It thrived predominantly in works of literature and developed, as linguist Dr. Bahri Hardev wrote "under the royal patronage and [...] schematic guidance of interested classes" in the "decadent Durbars of Delhi and Lucknow". Meanwhile, Hindi literature lagged far behind as the language was confined mainly to the lower-middle classes who stubbornly refused to depart from its antiquated predecessor Braj Bhasha. Thus, while authors like Wali Aurangabadi and Mir Taqi penned satires and verses infused with elegant Perso-Arabic borrowings, Hindi literature was stagnant, if not non-existent. It was not until the mid-nineteenth century that literary Hindi gained popularity and became widely circulated with acclaimed authors such as Harishchandra Bharatendu.

Socio-economic factors also played a large role in the divide, since Urdu was spoken predominantly among the upper class (the Awadh Elite) while Hindi was confined to rural areas and suffered a much smaller readership in the press

Another frequent misunderstanding is that during its spread, Urdu was adopted solely by Indian Muslims. As a matter of fact, according to the Indian census of 1900, the language was employed “by Musulmans and Hindus who [had] fallen under the influence of Persian culture”; one such Hindu community that proudly embraced this language and culture was the Kayasths and Khatris, of which the celebrated story writer Premchand was one, having sparked his career through the publishing of predominantly Urdu novels and only switching to Hindi during the latter half of his life.

Urdu essentially shares the basic grammatical features of Hindi. Similarly, Hindi itself has an equally irreplaceable vocabulary of Persian words (through centuries of foreign invasions dating as far back as 516 C.E.) that are so deeply ingrained within it that efforts to purge them have proved futile.

Consider the commonplace Hindi words of Persian origin

- Subha (morning)

- Jagah (place)

- Aaraam (rest)

- Riváj (custom)

- Hind (India) lit. "dwelling by the Indus"

Similarly, consider the Sanskritic origins of commonly used Urdu words (Tadbhava)

- Suraj (Sun) from Surya

- Chand (Moon) from Chandra

- Log (People) from Loka

- Dukh (Sorrow) from Duhkha

- Pyar (Love) from Priya

To rid Hindi of Persian Influence, or Urdu of Sanskrit influence, would be as futile as ridding Latin derivations from English, or Old Church Slavonic from Russian. Indeed, as Grahame Bailey noted, Persian influence upon Hindi can be likened to the impact of Norman French upon English. While the invasion did not manage to neatly transmit French to England, it instead involuntarily resulted in the creation of a rich amalgam rooted in German, Dutch, French, and Latin influences which we today know as English. As Charles Lyall wrote in his Sketch of the Hindustani Language, “Persian is no foreign idiom in India, and though its excessive use is repugnant to good taste, it would be a foolish purism and political mistake to attempt (as some have attempted to do) to eliminate it from the Hindi literature of the day”.

Therefore, it is arguably a useless debate to contend whether Hindi sprung from Urdu, or vice versa. Rather, these two languages (if one refers to them as such) had, at different times in history, merged and diverged, borrowed and mingled as the course of events developed.

The Invention of Differentiation

Thus far Hindi and Urdu were only distinct in so far as matters of style - and of course script - were concerned. It was during the nineteenth century which - through the commencement of an extensive printing programme and the project of standardising Indian vernaculars - created the religious and political distinctions which we today associate with Hindi and Urdu.

The opening of Fort William College in 1800, an institution that sought to educate servants of the EIC in various classical and vernacular languages, led to the dissemination of several grammars, dictionaries, and textbooks that necessitated that the once fluid and ambivalent Hindustani language become uniform with a distinct vocabulary. Interestingly, when John B. Gilchrist - a teacher of Hindustani and Persian at the college - attempted to compose a comprehensive Hindustani dictionary, he realised just how difficult such a task proved to be, remarking how one set of his Indian colleagues sought “far-fetched expressions on the deserts of Arabia”, while the rest were “groping in the dark intricate mines and caverns of Sanskrit”.

These taxonomic tendencies which were characteristic of the effects of colonialism made matters yet more complicated when Hindustani (Urdu) started being given a more privileged status than Hindi within the college; While Urdu was given its very own department in 1801, Hindi was left unrecognised as an official vernacular until 1825. Indeed, the replacement in 1837 of Persian with Urdu, which henceforth became the official court language, was established, as Hardev shrewdly remarks, under the “organised patronage” of the British for reasons of political expediency.

Socio-economic factors also played a large role in the divide, since Urdu was spoken predominantly among the upper class (the Awadh Elite) while Hindi was confined to rural areas and suffered a much smaller readership in the press. While Hindi was certainly taught in primary educational institutions, a gaping discrepancy was formed when government positions and important jobs started being offered largely to Urdu speakers. In fact, a rule passed in 1877 stated that knowledge of Urdu was mandatory for gaining employment offering a salary higher than Rs. 10, further accentuating the disparity.

Being dominant in the political, educational and judicial spheres, Urdu began to make use of esoteric and unintelligible Perso-Arabic words which greatly incensed not only Hindi purists, but also the general public. The works of Islamic reformists such as Shah Ismail and Maulvi Syed Abdullah, as well as the creation of madrasas across India and the circulation of Islamic pamphlets in Urdu, increasingly began associating the language with a Muslim identity.

However, the turning point occurred during the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the initiation of which was blamed in large part on the Muslims who were henceforth deemed untrustworthy in the eyes of the British. This was a withering blow to the then-growing status of Urdu, as well as the Muslim Elite which had, according to academician Tariq Rehman, to “consolidate its cultural power through the techniques and artifacts of European modernity” by publishing various tracts and treatises on Muslim loyalty and affinity to Western values. Although the Awadh Elite consisted of both Hindus and Muslims, it was exactly this fabricated sense of insecurity that would later lead to the creation of the Muslim League in 1906 - the most vocal defendant of Urdu as the language of Muslim culture.

Ayub Khan's military regime shortly re-established a pro-Urdu policy and subsequent efforts to suppress the Bengali Nationalist movement ultimately led to the fateful separation of East and West Pakistan in 1971

This also served as an opportune moment for the Hindi/Nagari movement to begin its agitation for granting Hindi the same rights as Urdu. The establishment of institutions such as the Nagari Pracharini Sabha in 1893 and the All India Hindi Sahitya Sammelan in 1910, coupled with Madan Mohan Malaviya's staunch advocacy, helped the movement gain momentum. Meanwhile, Urdu-Muslim extremism was also perpetuated through individuals like Syed Ahmad Khan who evoked the fear of Hindu dominance and reinforced the association of Urdu with Islam.

Thus, by the end of the 19th century, the two languages had effectively become what Alok Rai referred to as “Pandit-Hindi” and “Maulvi-Urdu”, as each was attributed its own religious and nationalistic identity. How the opening of a college in 1800 went from creating differences in mere stylistic flourishes all the way to the creation of two contentious nationalities is a harrowing illustration of the manipulation of languages as tools of religious and political division.

The Bengali Debacle

Following the devastating events of the Partition, Pakistan was officially declared an independent republic with its official language as Urdu and English. The country was, however, still not entirely “Urduised”, having its population of 68 million people consisting of 65% ethnic Bengalis.

The demand for Bengali as an official language of Pakistan had been campaigned for as early as 1948 when students from the University of Dhaka began a series of protests and strikes which were met by harsh suppression and censorship. In March of that year, Jinnah claimed at a public meeting that the State language of Pakistan would be “Urdu and no other language” (in spite of the fact that he himself could not speak it fluently).

In a meeting of the Constituent Assembly on the 24th of February, Dhirendra Nath Dutta, a prominent Bengali lawyer, and social worker, proposed the humble motion that Bengali be added alongside Urdu and English as the official language of Pakistan, spoken as it was by 44 million of its citizens. This was denounced as a seditious plan that, according to Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan, sought to "create a rift between the people of Pakistan" and "take away from the Muslims the unifying force that brings them together", perceived as it was as "the language of the Muslim culture and the Muslim civilisation". A certain Ghazanfar Ali Khan even boasted that "after a period of 10 or 15 years there may not be a single Bengali who will not be well conversant with the national language of the State". A programme of Islamising Bengali would thus later develop during the 50s through the set up of educational institutions that sought to teach Bengali in the Arabic script since it was perceived as too Sanskritized or “Hinduised”.

Nonetheless, it was precisely this fear of a disunited Pakistan that led to the amendment ultimately being negatived, giving way to a long series of protests, violent reprisals, and nationalist movements. (It was only a matter of a few days following Bengali independence that Dhirendra Dutta was abducted on March 29 and disappeared).

However, on 7 May 1954, Bengali did indeed get official status alongside Urdu in Article 214 of the 1956 constitution following the United Front’s sweeping victory, which made considerable progress in improving the status of East Pakistanis. Nonetheless, Ayub Khan's military regime shortly re-established a pro-Urdu policy and subsequent efforts to suppress the Bengali Nationalist movement ultimately led to the fateful separation of East and West Pakistan in 1971.

Today, there are about 3 million Bengalis still residing in the country, with most of them being concentrated in Karachi where they live under conditions of poverty and are frequently discriminated against. These Bengalis, despite having resided in Pakistan before 1971, are deprived of any official identification documents based on their language (which is considered foreign), making it impossible for them to obtain proper schooling or employment, even though the Citizenship Act of 1951 declared that anyone born after its enforcement would be entitled to the status of a citizen.

The plight of Bengalis in Pakistan displays just how far the politics of language has gone in discriminating against what is inherently a loyal community on the unfounded allegation that their creed and ethnicity are completely foreign.

The suppression of true “native” languages

It is ironic to reflect on how the imposition of Urdu merely replaced it with its colonial predecessor English as being the language of the educated, upper-middle strata. As the second language of the majority of the population, it is begrudgingly learned by the youth who barely manage to pass their examinations with sufficient grades, and simultaneously lose contact with their actual mother tongue.

Language is essentially a tool, and such a tool can either be put to its noblest use through engendering unity and understanding, or to its worst use by creating discord and enmity

Indeed, several of Pakistan's indigenous languages (those born on its very soil) are sidelined because they do not bear any sufficient association with Islam and are perceived as a threat to the country's unity. One of the most harrowing examples of this is Punjabi - the true “native” tongue of Pakistan, which, despite having over 80 million speakers in the country, has neither the status of a national, constitutional, or even provincial language.

Yaqoob Khan Bangash, a Lahore-based historian, wrote for the Wire about his visit to Punjabi University Patiala in India, and remarked incredulously on the language's honored place within the institution:

"The subsequent conference at Punjabi University Patiala simply had Punjabi as its main medium, with every single person speaking the language academically as well as colloquially. Such ease with Punjabi in educational institutions is simply unimaginable in Pakistani Punjab still, and its absence creates a gaping hole not only in the educational milieu of the province but also in the identity of Pakistani Punjabis, which is simply incomplete without learning, owning, and being proud of its language”.

Furthermore, Sindhi is the only regional language which is officially taught in educational institutions while the second and third most spoken languages, - namely Pashto and Seraiki - along with other innumerable tongues as varied as Hindko and Shina - are not taught in schools within their respective provinces.

Oddly enough, however, it is not even Urdu that ends up dominating the country's highest echelons, but English. As Rahman prudently remarks, “both [Urdu and Islam] are in fact subordinated to the interests of the Westernised, English-using, urban elite”. To add insult to injury, it does not help that Pakistan's national anthem was written in a language that apparently only 0.1% of the population understands, and which - since its arrival to the subcontinent - was spoken by only a small elite of poets and politicians.

In school curriculums, figures that were vital to the formation of the region’s history such as Kautilya, Raja Dahir, Ranjit Singh, or Ganga Ram, are either overlooked or completely avoided because they were either not directly involved in the formation of Pakistan or did not fit within the country's mold of a true national hero.

In the end, history stands witness to the fact that each time language has been used as a political maneuver, the results have been disastrous, leading to either the suppression, purging or even death of the language. Take for instance, the efforts of the Romans in 70 CE to extinguish Hebrew from Jerusalem, leaving it unspoken for more than a thousand years; or when, in 1932, the native speakers of Lenca and Cacaopera in El Salvador had to avoid using their language lest they be identified as indigenes and massacred; consider also the 1831 ban on teaching Irish Gaelic which not only stifled the language but also took away a rich trove of literature and history along with it.

Language is essentially a tool, and such a tool can either be put to its noblest use through engendering unity and understanding, or to its worst use by creating discord and enmity. Efforts to purge and distort them hardly prevail, as the figures today illustrate. That is because languages are born spontaneously out of communities and through the confluence of foreign borrowings and exchanges - not isolated classes of elect individuals. The complex history of Hindi-Urdu is, therefore, a rare example of what results when such a precarious - although well-meaning - instrument is used as a means to divide by attributing to languages a false affinity to distinct social, ethnic, and religious communities.