The tradition of reading books in Balochistan and its connection to political movements is deeply intertwined. The Baloch nation has regarded books as an important source for understanding their history, culture, and rights. As a politically oppressed community, books have helped them comprehend their identity and political struggle. Efforts to preserve the Balochi language and traditions have also promoted local literature. Writers and poets have documented Balochi folklore, history, and ideologies in written form, providing people with an opportunity to connect with their culture.

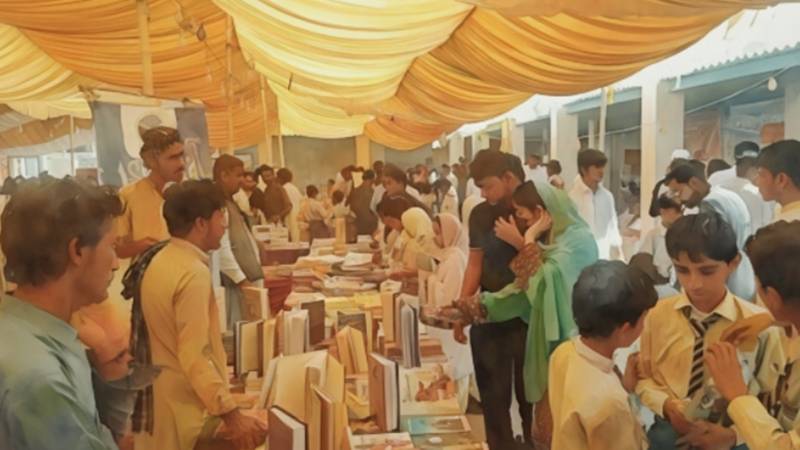

In 2014, the first two-day book fair was held in Gwadar, featuring only one stall and generating sales of one lakh rupees, which was a new record at the time. Since then, a four-day book fair has been organised annually. This year, books worth 28 million rupees were sold. This week, book fairs and seminars on the importance of books were held at four locations in Balochistan. The trend of book fairs and reading is becoming increasingly popular in the province. Another development this week was the inauguration of the Readers Club Corner, which was opened by young singer Sameek Baloch. The book fair series began in 2011, and the following year, book stalls were set up in remote areas of Balochistan. Locals took the initiative to acquire books from publishers, manage the stalls, and sell the books. This was a novel concept at the time. In a province like Balochistan, which is educationally underdeveloped, people are now purchasing books. Previously, except for Quetta, there was no such tradition in the interior regions of Balochistan. Over two years, stalls were set up in Noshki, Kharan, Turbat, Jaffarabad, Usta Muhammad, and Jacobabad. Now, even in underdeveloped districts like Dera Bugti, book fairs are held annually.

The Baloch nation has embraced books as a means of preserving their identity and struggle. Last month, the government imposed a ban on a student stall, and the students, along with their books, were jailed. Images of this incident went viral on social media. Similarly, books were banned at the University of Lasbela. In Dera Ghazi Khan, the Punjab government forcibly removed the stall of Baloch students. Human nature is such that the desire to access something increases when it is restricted, and this has been the case with the Baloch nation. This week, a seminar was organised in Quetta by book enthusiasts, focusing on the theme of restrictions on knowledge.

Now, even in underdeveloped districts like Dera Bugti, book fairs are held annually

The Nasirabad Literary Festival was held, led by renowned Baloch writer Panaah Baloch. People from across Pakistan attended, and thousands of books were sold. This remarkable achievement is attributed to an educated Baloch youth who purchases millions of rupees worth of books annually.

The growing trend of reading books among the oppressed Baloch nation is influenced by political restrictions. The Baloch people have started using books and literature as a means of reconciliation. Books written about their history, struggle, and rights foster unity and awareness, empowering society to fight against oppression.

Efforts to preserve the Balochi language and traditions have revived local literature. Writers and poets have documented oral histories, folklore, and political ideologies, encouraging people to connect with books to safeguard their identity. Books by Baloch poets such as Saif-ur-Rahman Mazari, Gul Khan Nasir, Karim Bakhsh Bugti, Mureed Bhilidi, Dilshad Masuri Bugti, Saeed Tabassum Mazari, Mubarak Qazi, Rafiq Mughairi, Shair Ghafoor Laghari, Jagha Buzdar, Ghulam Qadir Buzdar, and others have been sold. Additionally, books on national movements and Marxism have been among the bestsellers.

Books have helped the young Baloch generation, even without access to smartphones, the internet, or social media platforms. Online libraries and digital content on Baloch topics have helped overcome geographical barriers despite censorship.

Local NGOs and the Baloch diaspora have promoted literacy by funding educational programs, book distribution, and libraries.

Literature and pamphlets are being used to spread political ideologies and mobilise the youth.

The marginalised Baloch view their connection with books as a means of survival, whereas in developed societies, books are often seen as a source of entertainment or career advancement. However, there is a contrasting reality that cannot be ignored: the educational performance of the Balochistan government.

Nearly half of the population consists of children, totaling 7.3 million. Of these, 3 million (41%) are deprived of basic education, posing a serious threat to the province's future. There are 15,096 registered schools in the province, but 22% (3,321) are completely closed, while 50% (7,548) consist of only one room. More concerning is that 81% (12,228) of schools are limited to the primary level, making access to middle education difficult.

The quality of education is also severely affected. According to government tests, only 26% of primary-level children can read basic sentences, and only 30% understand basic math principles (such as addition/subtraction). Out of 400,000 children, only 133,000 meet educational standards. Unfortunately, 70% of children drop out after primary school, and only 35% reach high school. Due to the prevalence of cheating in high schools, only 1% of children make it to university.

Balochistan's education budget is 87 billion rupees, but developmental expenditures are only 12 billion rupees. The province's literacy rate is 27%, but 7,000 educated youth leave Balochistan every year in search of employment. Over the past five years, 31,607 people have migrated, as the provincial government provides only 20,000 jobs annually, of which only 5,000 are for educated individuals.

Reviving the educational system in Balochistan could not only eliminate extremism but also address employment opportunities, health issues, and economic instability. This requires restoring schools, balancing teacher appointments, focusing on girls' education, and linking employment projects with education. Instead of forcibly removing stalls, the provincial government should correct its policies, which could significantly improve the situation.