Like most Pakistanis, last week I watched in despair the drop scene of the three-week-old sit-in in Islamabad. A violent and abusive extremist group, ostensibly backed by elements in the army, celebrated a triumph that resulted in the resignation of the federal law minister.

For an already beleaguered government, it was a lose-lose situation from the start. The government saw the sit-in as a trap to further weaken its writ and authority. It initially tried to avoid walking straight into it by ignoring the problem, hoping it will go away. But charged with religious zeal, the protesters had enough backing to sustain them for weeks, if not months. The government’s priority was to avoid the use of force, but that reluctance made it look weak and ineffective. Restless for a clash, with each passing day the protesters were emboldened by the government’s meek and helpless response.

Opposition parties, the PPP and the PTI, seized on the opportunity to blame the government for incompetence and for the prolonged misery of commuters. But seeing how the leader of the Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan, Khadim Rizvi, abused and threatened their leaders, they found it expedient to keep mum and enjoy the show down from a safe distance.

The local administration was under constant pressure from the Islamabad High Court to clear the area. But by the time it decided to swing into action, the protesters were more than ready for the law-enforcement officials. The rowdy protesters received a major boost after the army chief advised the prime minister in a phone call that use of force against them would not be in the national interest. The fact that the phone call was made at a critical juncture and then widely publicised by the army’s media wing, the ISPR, sent a clear message to all involved that the government’s hands were tied in dealing with the protesters.

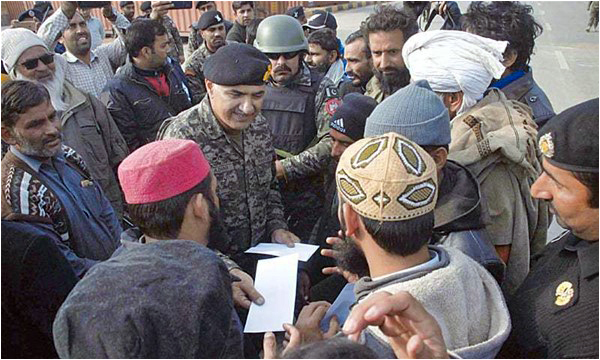

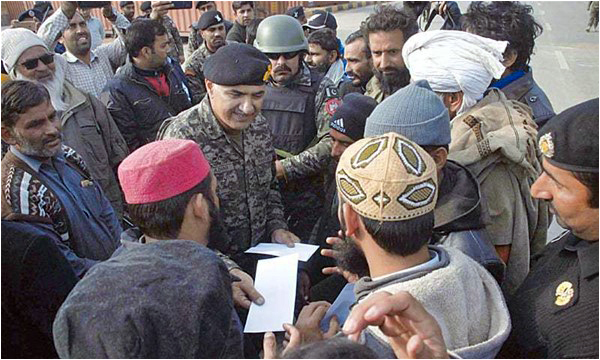

The security operation, carried out half-heartedly, without a clear chain of command and a contingency plan was hence doomed for failure before it had begun. Even then, according to witnesses, security personnel performed surprisingly well initially, driving the men out and clearing a large area they had occupied. But by most accounts, the tide turned when hundreds of angry and well-equipped rioters started descending on the scene. In the absence of timely reinforcements, riot police had no choice but to retreat. The protesters attacked security personnel, abducted and beat up some of them. Several reporters and photographers, deployed to the front lines of the chaos with total disregard to their own safety, were also abused, threatened and hurt in the clashes.

The agreement that emerged the next day made for shocking reading. It declared the protesters peaceful, promised to release the rioters and made the government responsible for financial compensation. It was unilaterally drawn up by the protesters and their handlers and brokered by none other than a serving Major General of the ISI. The helpless interior minister, Ahsan Iqbal, who received much of the flak for the botched operation later said he had little choice but to sign it.

The controversial agreement was widely denounced at home and abroad as capitulation. The Pakistani media generally heaped criticism on the civilian government, avoiding to comment on the army’s covert and overt role in the affair. But the international media was far more forthright in pointing out that the entire episode exposed the decisive role Pakistan’s army plays in orchestrating and then diffusing crises of this nature.

At home, perhaps the strongest criticism came from an Islamabad High Court judge, Shaukat Aziz Siddiqui. On Monday, he strongly criticised the army for playing the role of a mediator. He reminded the army that as a “part of the executive of the country, [it] cannot travel beyond its mandate” defined in the constitution. In a rather bold gesture, Justice Siddiqui wondered aloud how could an army officer play a role of a mediator in such matters.

The judge’s outspoken remarks did not go down too well. The army’s media wing, ISPR, “advised” news channels to underplay the court’s remarks. Some complied, others didn’t. The institution then fought back by encouraging TV commentators to heap praise on the institution for playing the saviour once again and preventing a potential bloodbath.

As if that were not enough, it seems a befitting response from the judiciary was also needed. It came from a judge of the Lahore High Court on Tuesday. While hearing a petition in an alleged enforced disappearance from Lahore, Justice Qazi Muhammed Amin praised the army for saving “the country from a huge catastrophe.” Unsurprisingly, his remarks were displayed prominently and repeatedly for hours, ostensibly to put to rest the searching questions raised by the IHC judge.

By mid-week, the self-styled protector of Prophet Muhammad’s (PBUH) honour and dignity, Khadim Rizvi, was well on his way through Punjab, as a celebrity. A section of the media went so far as to declare him as “a rising star” of Pakistani politics, and he now threatens to chew away at the vote bank of the mainstream parties.

But let’s not be deluded. Khadim Rizvi calls himself an Allama and Shaikh al-Hadith (scholar and expert), he is obviously anything but. The man plays on the hate-filled religious sentiment. He idealizes Mumtaz Qadri, the police bodyguard, who shot dead Punjab Governor Salmaan Taseer and openly incites violence against anyone who begs to differ with him. He is on record spewing venom against Hindus, Christians, Jews, Ahmadis, Deobandis, Shias and pretty much everyone who does not subscribe to his version of violent and extremist theology.

Pakistan already has its fair share of self-styled clerics who want to drag us back to the dark ages. This country can do without another dangerous man like him who seemingly threatens everyone, except the army. Our most powerful institution must refrain from creating a new monster. Khadim Rizvi is a dangerous man. He needs to be locked up for his actions, instead of being unleashed for political engineering.

@ShahzebJillani is a former BBC correspondent currently working as a senior executive editor for a primetime news show

For an already beleaguered government, it was a lose-lose situation from the start. The government saw the sit-in as a trap to further weaken its writ and authority. It initially tried to avoid walking straight into it by ignoring the problem, hoping it will go away. But charged with religious zeal, the protesters had enough backing to sustain them for weeks, if not months. The government’s priority was to avoid the use of force, but that reluctance made it look weak and ineffective. Restless for a clash, with each passing day the protesters were emboldened by the government’s meek and helpless response.

Opposition parties, the PPP and the PTI, seized on the opportunity to blame the government for incompetence and for the prolonged misery of commuters. But seeing how the leader of the Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan, Khadim Rizvi, abused and threatened their leaders, they found it expedient to keep mum and enjoy the show down from a safe distance.

The local administration was under constant pressure from the Islamabad High Court to clear the area. But by the time it decided to swing into action, the protesters were more than ready for the law-enforcement officials. The rowdy protesters received a major boost after the army chief advised the prime minister in a phone call that use of force against them would not be in the national interest. The fact that the phone call was made at a critical juncture and then widely publicised by the army’s media wing, the ISPR, sent a clear message to all involved that the government’s hands were tied in dealing with the protesters.

The security operation, carried out half-heartedly, without a clear chain of command and a contingency plan was hence doomed for failure before it had begun. Even then, according to witnesses, security personnel performed surprisingly well initially, driving the men out and clearing a large area they had occupied. But by most accounts, the tide turned when hundreds of angry and well-equipped rioters started descending on the scene. In the absence of timely reinforcements, riot police had no choice but to retreat. The protesters attacked security personnel, abducted and beat up some of them. Several reporters and photographers, deployed to the front lines of the chaos with total disregard to their own safety, were also abused, threatened and hurt in the clashes.

The agreement that emerged the next day made for shocking reading. It declared the protesters peaceful, promised to release the rioters and made the government responsible for financial compensation. It was unilaterally drawn up by the protesters and their handlers and brokered by none other than a serving Major General of the ISI. The helpless interior minister, Ahsan Iqbal, who received much of the flak for the botched operation later said he had little choice but to sign it.

The controversial agreement was widely denounced at home and abroad as capitulation. The Pakistani media generally heaped criticism on the civilian government, avoiding to comment on the army’s covert and overt role in the affair. But the international media was far more forthright in pointing out that the entire episode exposed the decisive role Pakistan’s army plays in orchestrating and then diffusing crises of this nature.

But let's not be deluded. Khadim Rizvi calls himself an Allama and Shaikh al-Hadith (scholar and expert), he is obviously anything but. The man plays on the hate-filled religious sentiment

At home, perhaps the strongest criticism came from an Islamabad High Court judge, Shaukat Aziz Siddiqui. On Monday, he strongly criticised the army for playing the role of a mediator. He reminded the army that as a “part of the executive of the country, [it] cannot travel beyond its mandate” defined in the constitution. In a rather bold gesture, Justice Siddiqui wondered aloud how could an army officer play a role of a mediator in such matters.

The judge’s outspoken remarks did not go down too well. The army’s media wing, ISPR, “advised” news channels to underplay the court’s remarks. Some complied, others didn’t. The institution then fought back by encouraging TV commentators to heap praise on the institution for playing the saviour once again and preventing a potential bloodbath.

As if that were not enough, it seems a befitting response from the judiciary was also needed. It came from a judge of the Lahore High Court on Tuesday. While hearing a petition in an alleged enforced disappearance from Lahore, Justice Qazi Muhammed Amin praised the army for saving “the country from a huge catastrophe.” Unsurprisingly, his remarks were displayed prominently and repeatedly for hours, ostensibly to put to rest the searching questions raised by the IHC judge.

By mid-week, the self-styled protector of Prophet Muhammad’s (PBUH) honour and dignity, Khadim Rizvi, was well on his way through Punjab, as a celebrity. A section of the media went so far as to declare him as “a rising star” of Pakistani politics, and he now threatens to chew away at the vote bank of the mainstream parties.

But let’s not be deluded. Khadim Rizvi calls himself an Allama and Shaikh al-Hadith (scholar and expert), he is obviously anything but. The man plays on the hate-filled religious sentiment. He idealizes Mumtaz Qadri, the police bodyguard, who shot dead Punjab Governor Salmaan Taseer and openly incites violence against anyone who begs to differ with him. He is on record spewing venom against Hindus, Christians, Jews, Ahmadis, Deobandis, Shias and pretty much everyone who does not subscribe to his version of violent and extremist theology.

Pakistan already has its fair share of self-styled clerics who want to drag us back to the dark ages. This country can do without another dangerous man like him who seemingly threatens everyone, except the army. Our most powerful institution must refrain from creating a new monster. Khadim Rizvi is a dangerous man. He needs to be locked up for his actions, instead of being unleashed for political engineering.

@ShahzebJillani is a former BBC correspondent currently working as a senior executive editor for a primetime news show