The history of the military's dominance of power structures in Pakistani society is certainly not as old as Pakistan itself: we started our existence as a state under the dominance of a civilian bureaucracy and a non-representative political elite. So much so that an eminent political historians has noted somewhere that Independence was a process in which power was transferred from the British colonial bureaucracy to a native (brown sahib) bureaucracy. The military started to make inroads into the power centres after the first Kashmir War and in the wake of a military pact with Washington. Tensions with India and a strengthening of relations with Washington were the two powerful determinants that paved the way for the Pakistani military to become a powerful actor in the power game in Pakistan. The 1948 Kashmir War symbolised what came to be described as a permanent state of tension with India. The 1954 US-Pakistan Defence Pact symbolised the strengthening of strong political, military and security relations with Washington. All this led to a process that culminated in the strengthening of non-representative state institutions at the cost of political process and nation building.

The Pakistani military got involved in an armed adventure—outside the Indo-Pak Subcontinent— for the first time in the wake of the 1979 Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, when Pakistani military-dominated intelligence services started aiding, training and financially supporting the Afghan Mujahideen against Soviet military forces. The withdrawal of the Soviet military from Afghanistan almost ten years later was perceived in Pakistani society generally and in the military in particular as a victory of clandestine assistance provided to the Afghan Mujahideen throughout ten years of Soviet occupation. Within years, the Soviet Union collapsed and was removed as a state from the map of the world. These events produced a kind of euphoria in the Pakistani society and military elite. They started to perceive themselves as something akin to conquerors or victors. This was even reflected in the statements, speeches and interviews of people like Generals (retd) Aslam Beg and Hameed Gul.

Events were happening in quick succession: military dictator General Zia-ul-Haq died in a plane crash and democracy was restored in Pakistan. Benazir Bhutto became the Prime Minister. Two developments originated in Islamabad because of the decisions made behind closed doors.

First, a development took place in a domestic political situation where Pakistani intelligence services became involved in machinations to disrupt the political process. Right wing political groups became partners of the intelligence services, with results that manifested in the military-backed no-confidence motion against Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto. Already, midnight knocks on the doors of political workers drawn from downtrodden sections of the society were a norm during Zia’s dark years. This continued into Benazir Bhutto’s era, with newly elected representative institutions helpless in the face of the dominance of the coercive machinery of the state by military and its intelligence services. How much of this was the product of the over-confidence that the military brass gained from their perceived success in Afghanistan is difficult to judge without proper academic research. Such research could possibly take place in the light of the declassification of state records and documents – if it ever takes place. One thing is certain: the repeated disruption of the political process in the late 1980s and the 1990s happened while the then Pakistani military top brass was celebrating their success in making the Soviet army run for their lives from Afghanistan.

The second development happened outside the country, when Pakistani intelligence services started planning to assist and militarise the Kashmir freedom struggle in 1989. It was no mere coincidence that Kashmiris were taking up arms when Afghan Mujahideen were celebrating their success against Soviet forces. Pakistan’s role in the 1989 Kashmir uprising is well documented, and much later, the military dictator General Musharraf conceded a lot of ground when he – on the coaxing of the Americans – committed to the Indians that he would curb Pakistani military assistance to Kashmiri Mujahideen.

A somewhat similar pattern, where over-confidence by the military leadership due to its successful role in Afghanistan translated into a disruptive political role in the domestic political system, started to repeat itself when a Taliban victory in Afghanistan became the writing on the wall. The Americans were on the run, just like Soviets. And they were seeking the help of the Pakistani military and its intelligence services to influence the decision-making process of the Afghan Taliban, to make their withdrawal as smooth as possible. The Pakistani military was staging a parallel military success on the home front in 2014 against the Pakistani Taliban, at the same time when the Americans were announcing that they would quit Afghanistan.

Two hurrahs for the military’s genius: a second superpower had been defeated in Afghanistan and domestic enemies like TTP were on the run.

Euphoria reached new heights.

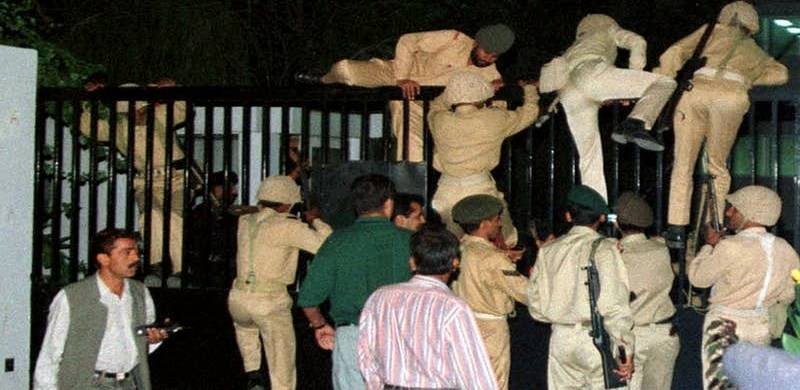

Not at all surprising is the fact that the military's latest foray into domestic politics took place in 2014, when their protégé Imran Khan started his bid for power in a tussle with the democratically elected government of Nawaz Sharif. In this era, Nawaz Sharif was labelled a RAW agent. A full propaganda machinery was launched to destabilise the elected government. Even bids were made to create divisions in the ruling party. Midnight knocks on the door became old fashioned. Now enforced disappearances became the new normal.

We are living in a changed world. The Pakistani state endured a lot of pressure from world powers during the past 20 years, and under this pressure they changed their attitudes towards regional security. Hence the euphoria of success in Afghanistan and on the home-front didn’t produce regional adventure. In fact, the Pakistani military and intelligence services might be contributing to the regional project led by Russia, China and Iran to stabilise Afghanistan in the face of the growing threat of radical Sunni extremist groups.

This is my personal understanding of post-Zia Pakistani history. I know that I won’t be able to fully academically validate it, until and unless a major portion of Zia-era and subsequent government records and documents are declassified. So this article could be termed as a view from an observer, an outsider of the power corridors. My understanding of history forces me to take with a pinch of salt General Bajwa’s announcement about the military decision to remain apolitical. The military is too deeply immersed in the affairs of the state to remain apolitical for too long. Moreover, the military has definite political interests, and no amount of criticism from the political elite could make them relinquish these interests.

The Pakistani military got involved in an armed adventure—outside the Indo-Pak Subcontinent— for the first time in the wake of the 1979 Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, when Pakistani military-dominated intelligence services started aiding, training and financially supporting the Afghan Mujahideen against Soviet military forces. The withdrawal of the Soviet military from Afghanistan almost ten years later was perceived in Pakistani society generally and in the military in particular as a victory of clandestine assistance provided to the Afghan Mujahideen throughout ten years of Soviet occupation. Within years, the Soviet Union collapsed and was removed as a state from the map of the world. These events produced a kind of euphoria in the Pakistani society and military elite. They started to perceive themselves as something akin to conquerors or victors. This was even reflected in the statements, speeches and interviews of people like Generals (retd) Aslam Beg and Hameed Gul.

Events were happening in quick succession: military dictator General Zia-ul-Haq died in a plane crash and democracy was restored in Pakistan. Benazir Bhutto became the Prime Minister. Two developments originated in Islamabad because of the decisions made behind closed doors.

First, a development took place in a domestic political situation where Pakistani intelligence services became involved in machinations to disrupt the political process. Right wing political groups became partners of the intelligence services, with results that manifested in the military-backed no-confidence motion against Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto. Already, midnight knocks on the doors of political workers drawn from downtrodden sections of the society were a norm during Zia’s dark years. This continued into Benazir Bhutto’s era, with newly elected representative institutions helpless in the face of the dominance of the coercive machinery of the state by military and its intelligence services. How much of this was the product of the over-confidence that the military brass gained from their perceived success in Afghanistan is difficult to judge without proper academic research. Such research could possibly take place in the light of the declassification of state records and documents – if it ever takes place. One thing is certain: the repeated disruption of the political process in the late 1980s and the 1990s happened while the then Pakistani military top brass was celebrating their success in making the Soviet army run for their lives from Afghanistan.

The second development happened outside the country, when Pakistani intelligence services started planning to assist and militarise the Kashmir freedom struggle in 1989. It was no mere coincidence that Kashmiris were taking up arms when Afghan Mujahideen were celebrating their success against Soviet forces. Pakistan’s role in the 1989 Kashmir uprising is well documented, and much later, the military dictator General Musharraf conceded a lot of ground when he – on the coaxing of the Americans – committed to the Indians that he would curb Pakistani military assistance to Kashmiri Mujahideen.

A somewhat similar pattern, where over-confidence by the military leadership due to its successful role in Afghanistan translated into a disruptive political role in the domestic political system, started to repeat itself when a Taliban victory in Afghanistan became the writing on the wall. The Americans were on the run, just like Soviets. And they were seeking the help of the Pakistani military and its intelligence services to influence the decision-making process of the Afghan Taliban, to make their withdrawal as smooth as possible. The Pakistani military was staging a parallel military success on the home front in 2014 against the Pakistani Taliban, at the same time when the Americans were announcing that they would quit Afghanistan.

Two hurrahs for the military’s genius: a second superpower had been defeated in Afghanistan and domestic enemies like TTP were on the run.

Euphoria reached new heights.

Not at all surprising is the fact that the military's latest foray into domestic politics took place in 2014, when their protégé Imran Khan started his bid for power in a tussle with the democratically elected government of Nawaz Sharif. In this era, Nawaz Sharif was labelled a RAW agent. A full propaganda machinery was launched to destabilise the elected government. Even bids were made to create divisions in the ruling party. Midnight knocks on the door became old fashioned. Now enforced disappearances became the new normal.

We are living in a changed world. The Pakistani state endured a lot of pressure from world powers during the past 20 years, and under this pressure they changed their attitudes towards regional security. Hence the euphoria of success in Afghanistan and on the home-front didn’t produce regional adventure. In fact, the Pakistani military and intelligence services might be contributing to the regional project led by Russia, China and Iran to stabilise Afghanistan in the face of the growing threat of radical Sunni extremist groups.

This is my personal understanding of post-Zia Pakistani history. I know that I won’t be able to fully academically validate it, until and unless a major portion of Zia-era and subsequent government records and documents are declassified. So this article could be termed as a view from an observer, an outsider of the power corridors. My understanding of history forces me to take with a pinch of salt General Bajwa’s announcement about the military decision to remain apolitical. The military is too deeply immersed in the affairs of the state to remain apolitical for too long. Moreover, the military has definite political interests, and no amount of criticism from the political elite could make them relinquish these interests.