“That men do not learn very much from the lessons of history is the most important of all the lessons of history”—Aldous Huxley

In one of his most popular plays Twelfth Night, Act II, scene V, William Shakespeare writes: “Some are born great, some achieve greatness and some have greatness thrust upon them.”

Although meant to be a joke to amuse the audience, the fact is that this quote has tremendous philosophical profoundness for those who can understand. Many around the globe who are famous in various fields have definitely worked hard enough to reach that level. Whether they are related to education, athletics or other professional areas, there cannot be two opinions about the intensity of hard labour that goes into making them great. On the contrary, heads of state are mostly those who are either there by virtue of their birth, by accidentally being propelled into politics, by choosing to adopt politics or are installed by someone.

The north-west part of South Asia is a unique region where governments come and go, not as a matter of an established ‘democratic’ system, but at the whims of some particular forces. Perhaps this is due to the distinctive general nature of the subcontinent that has witnessed the rise and fall of empires and dynasties amid intrigues, scandals, conspiracies, loyalties, betrayals, battles, annexations and power play. Stories of the yesteryears are told again and again with the objective of reminiscing past glory, past mistakes, past hurt, but principally the idea is to learn lessons. As the philosopher George Santayana aptly remarked: “Those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

We study history, often reluctantly as a compulsory subject in schools. The idea is that we must have a sound knowledge about our place of birth and our identity so we can effectively connect to our roots, thus developing a sense of belonging, which is integral to our mental and physical health. Although children are usually weary of remembering unfamiliar names and dates, yet subconsciously they absorb a lot of information which comes handy as they grow and understand whatever goes around them. Some of course move on to deeper realms of history and specialize in various aspects of the past that enables them to make in-depth analysis of the present so as to foretell the future.

One of the conclusions drawn from history dwells on the concept of kingmakers. The term ‘kingmaker’ is used to describe someone having power and influence and who, embellished with political connections, great wealth, or military prowess has the capability to gain an outcome that would otherwise not be possible especially where it relates to heading a country or ascending a throne. Two important characteristics that can be ascribed to kingmakers are that they are themselves not eligible for a particular position and they usually appear on the forefront during a power struggle between two or more parties.

Now, the million-dollar question is whether it is better to be a contestant in fighting for power or be the one pulling the strings from behind the scene. This definitely relates to the intentions of the kingmakers who can use their influence for noble purposes or abuse it to meet their own nefarious ends. A few interesting historical examples would highlight the role kingmakers play in helping regimes to prosper or decline.

Chanakya, also known as Kautilya was a 4th century BCE philosopher in ancient India. A man of great acumen, he switched his loyalty from the Nanda dynasty, having been insulted by King Dhana Nanda, to mentor young Chandragupta Maurya. With his extraordinary intellect, he managed to help the warrior raise an army and eventually overthrow the Nandas to establish the Mauryan Empire famously known as the Golden Period of Hinduism around 321 BCE.

In European history, Julius Caesar Augustus became the first emperor of Rome in 67 BCE. From that time onwards, the Praetorian Guard acted as his personal security. Over 300 years as an institution, they grew in power that led them to corrupt practices which in turn caused them to safeguard their own position before that of the emperor whom they had vowed to protect. They did not hesitate in getting rid of any ruler who went against their interests, thus assassinating over a dozen Roman emperors. Their greed reached its peak when the last emperor Pertinax tried to discipline the Praetorian Guard. They killed him and offered their support to the highest bidder in an auction for the throne. Didius Julianaus won the bid and ruled for nine weeks before he too was exterminated. It was not until Constantine ultimately gained power that the Guard was permanently dissolved in 312 CE.

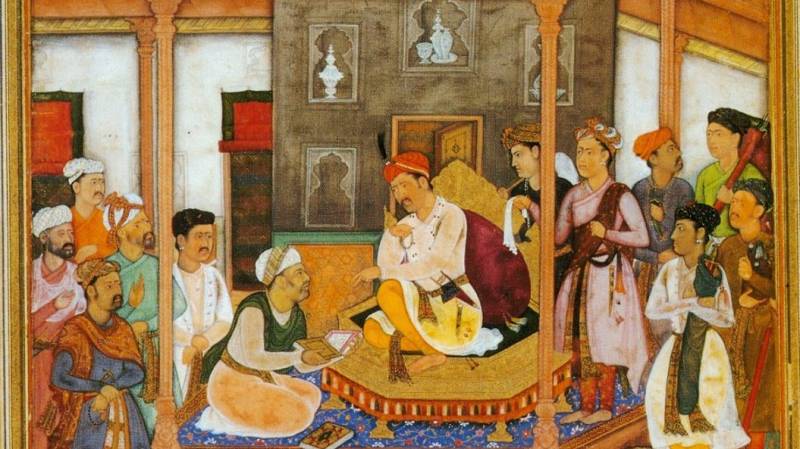

On his death in 1707, Aurangzeb left a mighty Mughal Empire followed by short reigns of his descendants who were either crowned or deposed by two highly influential courtiers, best remembered as the Sayyid Brothers who were given titles and high ranking positions with the court. For a decade they continued their power game until Muhammad Shah became king in 1719, who having garnered support of the disgruntled nobility, eliminated them for good.

Females too have had their share in making and breaking kings. They have also proved influential in governing affairs of the kingdom although only a handful have actually wielded power in Indo-Pakistan history, but many have stood ground behind kings and princes enjoying all the privileges without burdening themselves with responsibility. In fact, most kingmakers avoid being held accountable for acts performed at their behest by the monarchs.

One would imagine that twenty first century would see sensible approach of those who are desirous of leading their nations especially when history has so much to offer. However, surprisingly, in today’s world of rising consciousness, we have experienced liberated men running after ‘spiritual clairvoyants’ for leading them to seats of power even if it means making themselves look like utter fools. Such are the kinds that never learn from the past.