shaam aa.e aur ghar ke liye dil machal uThe

shaam aa.e aur dil ke liye koī ghar na ho

(Evening falls, and the heart longs for home,

Evening falls, but the heart has no home)

(Akhtar Usman)

This couplet embodies the alienation that both of us have dreadfully felt throughout our lives. Despite being born, raised, and living (though Fammaz is now dwelling in the UK) in our beloved city, Peshawar, we are somehow phased out—not physically, but rather in the socio-political-economic realms. Our city is hegemonised cap-a-pie by “outsiders”; our existence is mortified. Most of the Pashtuns, and almost every other Pakistani, don’t even acknowledge our existence, and the people who are aware of us somehow label us as a minuscule “misc.” category of people dwelling in Peshawar.

This is the backdrop against which we are asserting our beings. While it may be seen as another bunch of words problematising a prevailing ethno-social issue, for us, this is not just another pedestrian problem among many, but rather an existential impasse that needs to be underscored with as much radicality as possible. Without acknowledgment of our (Peshawiris') roots, we are disillusioned with our own identity and sense of belonging, in contrast to the prevailing ethno-culturalism (Pashtunwali).

Further, this may also be painted as a negative project—a call against the dominating ethno-cultural groups. For us, this is a blossoming action; preserving our own roots and culture has nothing to do with undermining other ethno-cultures in itself, rather the incessant propagation (by crushing others) of it.

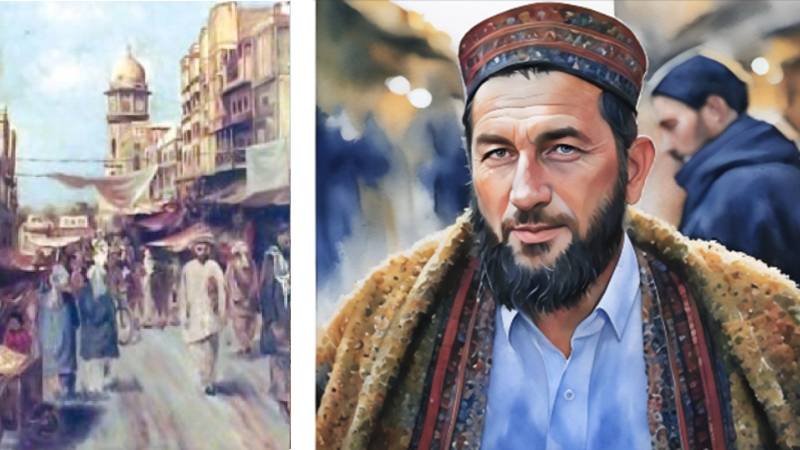

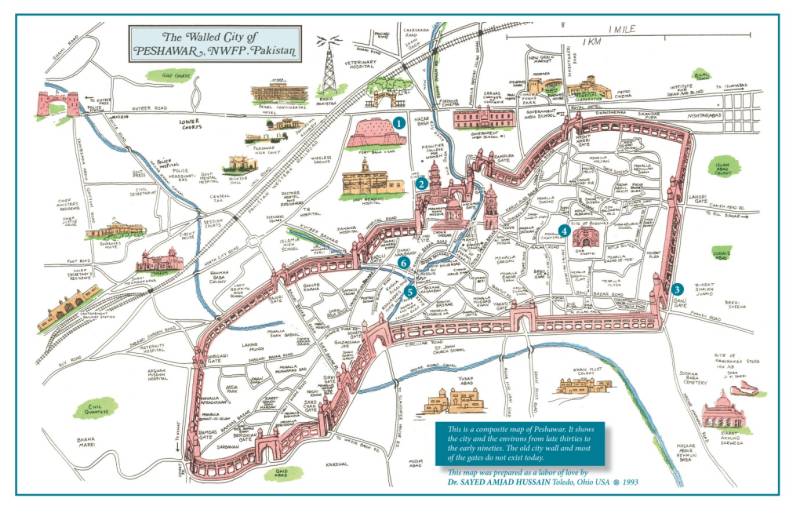

The walled city of Peshawar, one of the oldest living cities in the world, has long been a hub of cultural vibrancy and historical significance. Known for its role as a crossroads of civilisations, Peshawar was once the heart of the Gandhara civilisation, a beacon of Buddhist art and learning. Over centuries, it has seen waves of rulers and travellers—from the Mauryans and Kushans to the Mughals and Sikhs. Amid this rich tapestry of history emerged the indigenous Hindko-speaking community, the Peshawiris (aka Peshoris), as they are affectionately called. These city dwellers, or Shehris, have been integral to the city’s social and cultural fabric, yet today they find themselves marginalised and their heritage fading into obscurity.

The Peshoris trace their roots to Central Asia, having settled in Peshawar over a millennium ago. They established themselves as a thriving community, blending influences from Persian, Indian, and Central Asian cultures. The Hindko language, though now replaced by the lingua franca (Pashto), with its melodic tone and rich vocabulary, became their means of expression, encapsulating their identity. Peshawiris were historically known for their hospitality, intellect and resilience. They were not merely inhabitants of the city; they were its heartbeat, contributing to its art, literature, and culinary traditions. Renowned figures like Patras Bokhari and the artist Gulgee stand as testaments to their intellectual legacy.

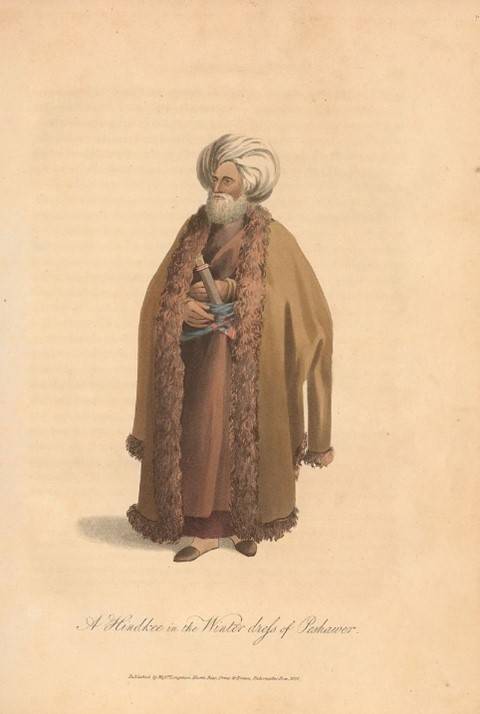

The Hindko language, once dominant in the streets of Peshawar, is now a minority tongue. Traditional attire such as the Peshawri kulla and mazari topi, as well as the vibrant idioms of Hindko are fading into obscurity

For centuries, Peshawar flourished under indigenous stewardship, but the arrival of external influences began to alter its demographic landscape. The Sikh invasion in 1818 marked one of the first major disruptions, with the city falling under Sikh rule for over two decades. The British annexation in 1849 further shifted the power dynamics, as they introduced administrative changes and expanded the city's boundaries. The early 20th century saw another wave of migration as Pashtun tribes from surrounding regions moved into Peshawar, attracted by its economic opportunities and urban appeal. These migrations were relatively small in scale and integrated with the city’s diverse populace.

Elphinstone

The Soviet-Afghan War in 1979, however, marked a turning point. The influx of Afghan refugees into Peshawar fundamentally transformed its demographic composition. Over the next two decades, the city swelled with millions of refugees, many of whom settled permanently. This rapid population growth placed immense pressure on the city’s resources and diluted its indigenous identity. By the late 20th century, Peshawar had expanded far beyond its historic walled confines. Suburbs like Hayatabad were established to accommodate the growing population, yet these new areas lacked the soul of old Peshawar. The Hindko-speaking Peshoris, once the majority, now constitute less than 2.2% of the city’s population.

The culinary traditions of the Peshoris offer a window into their rich culture. Signature dishes such as channa mewa pulao (rice topped with chickpeas and raisins, different from Kabuli Pulao), shola (variant of charsadda’s short grain rice) , panchay (trotters), bukhara haleem (sweet variant of thick stew, similar to the Persian haleem), and their unique qahwa reflect a blend of flavours that speak to their Central Asian and subcontinental heritage. These delicacies, often prepared with intricate techniques passed down through generations, were once staples of Peshawari households and festivals. The Peshori style of hospitality, where food was an expression of love and community, remains a cherished memory for those who experienced it.

Despite the demographic and cultural erosion, Peshoris have made significant contributions to Peshawar’s history. They played a pivotal role in the struggle for independence from British colonial rule. Many were part of the Khudai Khidmatgar movement led by Bacha Khan, advocating for non-violence and self-reliance. The Qissa Khwani massacre of 1930 is etched in history as a moment of profound sacrifice, with Peshoris standing at the forefront of resistance against British tyranny. Figures like Hakeem Jalil and Farigh Bukhari exemplify their intellectual and revolutionary spirit, contributing to literature and activism.

Today, the story of the Peshoris is one of resilience against overwhelming odds. As waves of migration and urban sprawl reshaped Peshawar, the Peshoris’ unique identity was increasingly overshadowed. The Hindko language, once dominant in the streets of Peshawar, is now a minority tongue. Traditional attire such as the Peshawri kulla and mazari topi, as well as the vibrant idioms of Hindko—including phrases like mara, shodday, and lalay—are fading into obscurity. The Peshoris find themselves alienated, struggling to preserve their heritage in a city that no longer feels like their own.

Yet, the Peshoris’ story is not one of defeat. Their resilience shines through in their efforts to safeguard their traditions and language. The preservation of Peshori cuisine, the revival of Hindko literature, and the documentation of their history are steps toward reclaiming their cultural identity. The objective must be clear: to celebrate the contributions of the Peshoris while fostering an inclusive narrative that acknowledges their rightful place in Peshawar’s past, present, and future. It is imperative to protect their heritage, not as a relic of the past but as a living, breathing testament to the diversity and richness of Peshawar’s history.

Way forward

To address the cultural diminishment faced by Peshawiris and preserve their rich heritage, several measures must be taken. Building a credible and sustained network of Peshawiris is crucial. This network should serve as a platform to discuss, celebrate, and preserve their origins, history, cultural norms, and notable figures—both celebrated and overlooked. Forums, both online and offline, can facilitate regular dialogue, while partnerships with academic institutions and cultural organisations can amplify these efforts. Creating a digital archive to safeguard the history, oral traditions, and cultural practices of Peshawiris will also be a significant step forward.

Equally important is the propagation of Peshawiri identity. Utilising social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, X (formerly Twitter), and TikTok, the community can actively promote their cultural heritage, share notable stories, and advocate for language preservation. Engaging, educational content on these platforms can ensure that the Peshawiri heritage resonates with a global audience.

A pivotal initiative would be to propose the establishment of a 'Walled City of Peshawar' Authority, modelled after successful organisations like the Lahore Walled City Authority and Historic England. Such a body could focus on preserving and restoring historical sites, architecture, and literature while planning infrastructure in harmony with the city’s heritage. It would involve local Peshawiris in decision-making processes regarding cultural preservation and development, promote tourism to raise awareness of the city’s rich history, and formalise economic opportunities arising from tourism to create sustainable livelihoods.

Furthermore, developing skill-building initiatives tailored to the Peshawiri community’s needs can significantly enhance their socio-economic prospects. These initiatives might include workshops or online sessions for career development, mentorship programs connecting Peshawiris with professionals abroad, and webinars on practical skills such as resume writing, public speaking, and digital literacy. Such efforts could foster a skilled talent pool and prepare individuals for both local and international job markets.

Advocacy for the inclusion of Peshawiri history in textbooks is another essential step. Collaborating with educational authorities, historians, and authors to incorporate a dedicated chapter on the Peshawiri community and its history will ensure accurate representation and recognition of their contributions and struggles. Alongside this, quotas in colleges, universities, and job markets specifically allocated to the Peshawiri community should be established. Petitions, awareness campaigns, and community forums can support these efforts, highlighting quotas as a means to preserve cultural diversity and secure equal opportunities for future generations.

Lastly, preserving the Hindko language, particularly the Peshori dialect, must remain a central focus. Efforts to document and promote the language through literature, transcreations of global classics, and public awareness campaigns will help ensure that this linguistic heritage thrives in the modern era. These collective efforts will not only protect the Peshawiri heritage but also reaffirm their rightful place in the historical and cultural narrative of Peshawar.

As part of a broader endeavour to preserve the Hindko language (specifically the Peshori dialect), we are here striving to transcreate Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18.

Tanu mai siyale di tiyari kawa?

Kho toon tay aur bhi haseen te jameel hai

Hawawan te larzaa chor diyan baharan de mashoom phulla nu

Te garmiyan di muddat hi zara jhi reh gayi hai

Kaddi tere ijyay laskhare haunden kay roshni bhi kachi reh jawe

Tere waal sone aar urn, tay tera rang chandni hai

Kho sohne sohne chehre bhi kaddi kaddi murjaa janden

Jwand te naam hi badalde halatan da haundan hai

Lekin watt bhi dilan de chiragh kaddi na bhuj soon

Na hi hilda is dil si, teri ulfat da langar hai

Pawe marna bhi asaan hojawe, wat bhi taluq reh si

Mere khattan di reet, mere lahfuz, shiddat una di lafaani hai

Jaddo tukul ankhiyan de chiragh bal sun, te mera saa chal si

Teri tashnagi zinda reh si, pawe dunya hai ya barzakh hai