On February 24th, the finance ministers of the G20 nations met in Bengaluru, India, to debate on a variety of pressing issues confronting the global economy and developing countries. One of these pieces of the discussion centered around debt relief for distressed nations, yet the summit, led by India, was unable to come to any viable conclusion due to a deadlock between China, the world's largest bilateral lender, and the Western Bloc.

For some time, Beijing has held the point of view that multilateral institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank should be involved in debt restructuring negotiations, forfeit their status as preferred creditors, and take up a fair portion of the financial burden of restructuring.

As per an article in the Financial Times, “Critics claim removing so-called ‘preferred creditor’ status would prove disastrous, raising lenders’ cost of funds — and their capacity to provide finance at much lower interest rates than borrowers could get elsewhere. Borrowers in the developing world are also alarmed by any threat to the creditor protection that underpins the triple-A credit ratings of the World Bank and other development banks.”

Hence, these differences are one of the biggest impediments to debt relief activities across the globe. “Sri Lanka, which defaulted last year, has also not yet received the financing assurances it needs from China to finalise an IMF assistance programme. Other countries that have borrowed heavily from Beijing and western creditors, such as Pakistan and Egypt, are at risk of following the two into default this year, the article further added.

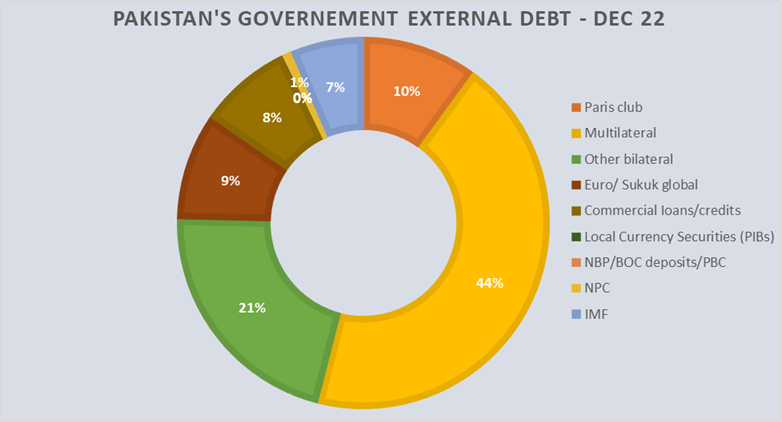

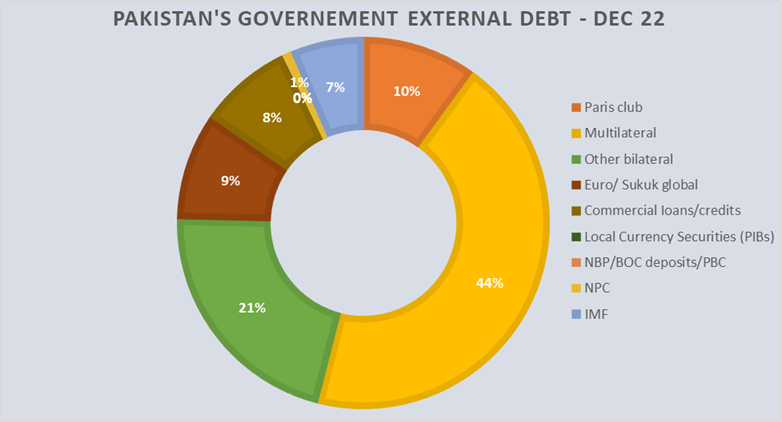

Source: SBP

But, what one fails to understand is why is this such a contentious issue. The answer probably lies in the business model of Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) like the World Bank Group.

The Business Model

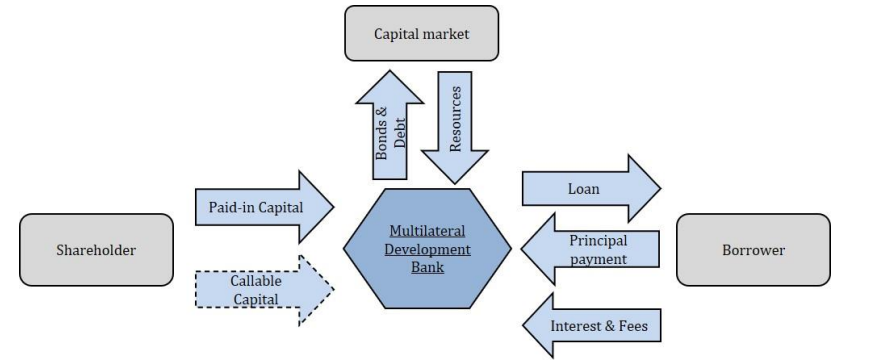

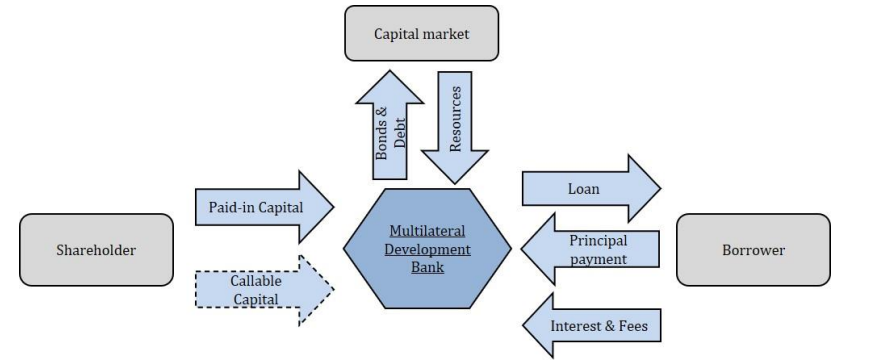

As per a study published by Laura Peitz, “MDBs are capitalized by their shareholders (Nations), who provide MDBs with capital proportional to the shares they hold, which forms (part of) MDBs’ equity. Against this capital base, MDBs issue bonds and debt in private capital markets, i.e. borrow from private investors. The resources thereby raised are then on-lent to MDB borrowers, which can be sovereign states and private sector entities. These, in turn, make principal payments on the loans received as well as pay interest rates and (potentially) fees. Net income generated from the payment of interest and fees can then be allocated to reserves, which together with the paid-in capital provided by shareholders form MDBs’ equity.”

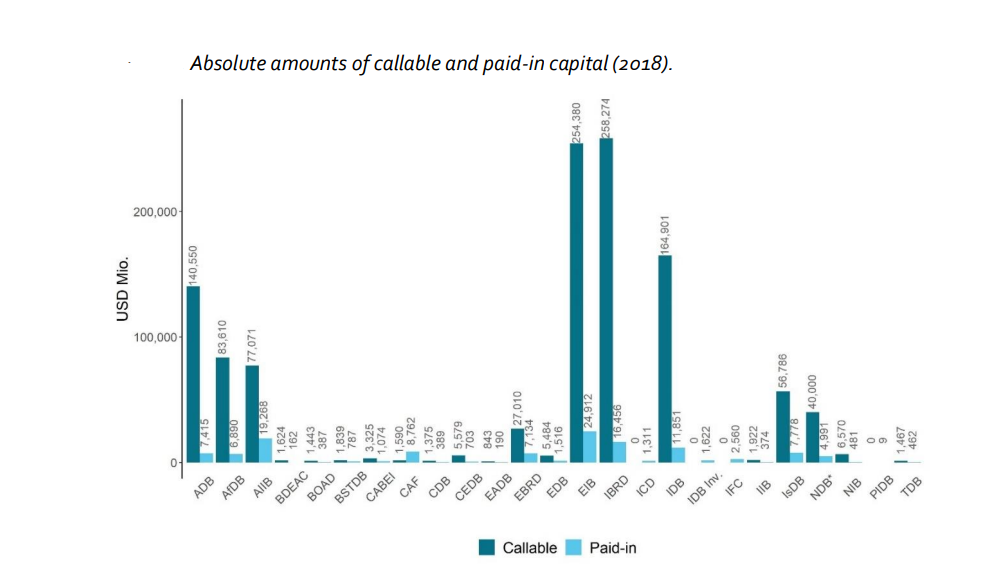

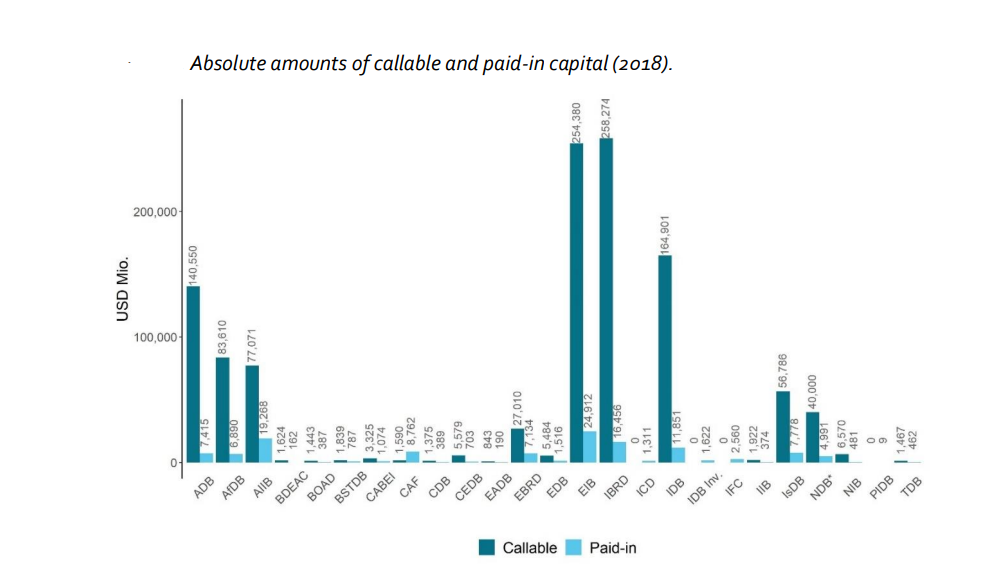

“MDB members usually pay in only a small portion of their capital subscriptions (paid-in capital), while the bulk of subscribed capital is not paid in but can be called by MDBs (callable capital), in the case they default on their obligations and when all other resources are exhausted. Callable capital hence serves as collateral for the unlikely event that an MDB cannot cover its own obligations with its own borrowers’ repayments and available liquidity. Up to now, no call on capital has ever been made by MDBs,” the study added.

Note: Frequently, the IBRD and IDA, which together form the World Bank, are considered as one organization.

Thus, MDBs have an effective business model wherein they leverage their capital base, allowing them to borrow more money than their equity and on-lend it to borrowers. This arrangement enables MDBs to make efficient use of limited public funds. The conditions of MDB loans tend to be more advantageous to borrowers like Pakistan than those available from global capital markets as credit ratings for a lot of developing nations are in the lower echelons.

https://twitter.com/KhurramHusain/status/1630544736107757569?ref_src=twsrc%5Egoogle%7Ctwcamp%5Eserp%7Ctwgr%5Etweet

Additionally, MDB loans are given preferred creditor status (PCT) which means that, in the event of payment difficulties, lenders may prioritize repayment of MDB debt over other creditors. This is partly because MDBs are lenders of last resort, continuing to lend even in difficult financial times.

Therefore, MDBs are not reliant on continual capital injections from their shareholder nations, rather their success is based on sustaining access to capital at advantageous terms. Such terms are contingent on the market's trust in their financial strength, which is indicated by ratings provided by Credit Rating Agencies, such as Fitch, Moody's, and Standard & Poor's (S&P). Generally, the largest MDBs have earned the best possible credit ratings (AAA and equivalent) thanks to the status of preferred creditor and the existence of callable capital.

The Standoff

The structure of MDBs discussed above explains why the western block which controls the global MDBs is cautious about a change in the preferred creditor status.

Recently, as reported by the Financial Times, a group of developing economies issued an internal note that stated, “The World Bank’s high rating was necessary to be able to raise funds at a cost that would enable lending at below-market rates. This is the very rationale underlying the [multilateral development bank] concept.”

“The note was signed by countries including Brazil, Argentina, Chile and Peru in South America, as well as by Pakistan, Iran, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, India, Indonesia, Singapore, Vietnam, China, Saudi Arabia and Russia, plus Egypt and more than two dozen African nations.”

When considering Beijing's seemingly conflicting stance, it is important to acknowledge that there are multiple Chinese creditors. This is because China's Finance, Trade, and Foreign Ministries, Central Bank, and National Development Agency each have separate and occasionally divergent mandates and objectives.

Furthermore, China is aware that any debt forgiveness on the part of multilateral institutions would be financed by the investment incomes of the MDBs and additional funding from its donor countries, which would have a direct financial impact on the Paris Club and the Western Bloc.

In light of this, it seems the stalemate is likely to remain in place, though the rise of China and other nations as global lenders is likely to spur a shift in the existing restructuring frameworks and the status of Multilateral organizations. Establishing an agreement will be tough, but potential solutions have been floated.

At the G20 meetings last year, a report was tabled that suggested five steps to assist the MDBs: (1) adapt the approach to defining risk tolerance, (2) give greater consideration to callable capital, (3) make use of financial innovations, (4) improve CRAs' assessment of MDB financial strength, and (5) increase access to MDB data and analysis.

For some time, Beijing has held the point of view that multilateral institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank should be involved in debt restructuring negotiations, forfeit their status as preferred creditors, and take up a fair portion of the financial burden of restructuring.

As per an article in the Financial Times, “Critics claim removing so-called ‘preferred creditor’ status would prove disastrous, raising lenders’ cost of funds — and their capacity to provide finance at much lower interest rates than borrowers could get elsewhere. Borrowers in the developing world are also alarmed by any threat to the creditor protection that underpins the triple-A credit ratings of the World Bank and other development banks.”

Hence, these differences are one of the biggest impediments to debt relief activities across the globe. “Sri Lanka, which defaulted last year, has also not yet received the financing assurances it needs from China to finalise an IMF assistance programme. Other countries that have borrowed heavily from Beijing and western creditors, such as Pakistan and Egypt, are at risk of following the two into default this year, the article further added.

Source: SBP

But, what one fails to understand is why is this such a contentious issue. The answer probably lies in the business model of Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) like the World Bank Group.

The Business Model

As per a study published by Laura Peitz, “MDBs are capitalized by their shareholders (Nations), who provide MDBs with capital proportional to the shares they hold, which forms (part of) MDBs’ equity. Against this capital base, MDBs issue bonds and debt in private capital markets, i.e. borrow from private investors. The resources thereby raised are then on-lent to MDB borrowers, which can be sovereign states and private sector entities. These, in turn, make principal payments on the loans received as well as pay interest rates and (potentially) fees. Net income generated from the payment of interest and fees can then be allocated to reserves, which together with the paid-in capital provided by shareholders form MDBs’ equity.”

“MDB members usually pay in only a small portion of their capital subscriptions (paid-in capital), while the bulk of subscribed capital is not paid in but can be called by MDBs (callable capital), in the case they default on their obligations and when all other resources are exhausted. Callable capital hence serves as collateral for the unlikely event that an MDB cannot cover its own obligations with its own borrowers’ repayments and available liquidity. Up to now, no call on capital has ever been made by MDBs,” the study added.

Note: Frequently, the IBRD and IDA, which together form the World Bank, are considered as one organization.

Thus, MDBs have an effective business model wherein they leverage their capital base, allowing them to borrow more money than their equity and on-lend it to borrowers. This arrangement enables MDBs to make efficient use of limited public funds. The conditions of MDB loans tend to be more advantageous to borrowers like Pakistan than those available from global capital markets as credit ratings for a lot of developing nations are in the lower echelons.

https://twitter.com/KhurramHusain/status/1630544736107757569?ref_src=twsrc%5Egoogle%7Ctwcamp%5Eserp%7Ctwgr%5Etweet

Additionally, MDB loans are given preferred creditor status (PCT) which means that, in the event of payment difficulties, lenders may prioritize repayment of MDB debt over other creditors. This is partly because MDBs are lenders of last resort, continuing to lend even in difficult financial times.

Therefore, MDBs are not reliant on continual capital injections from their shareholder nations, rather their success is based on sustaining access to capital at advantageous terms. Such terms are contingent on the market's trust in their financial strength, which is indicated by ratings provided by Credit Rating Agencies, such as Fitch, Moody's, and Standard & Poor's (S&P). Generally, the largest MDBs have earned the best possible credit ratings (AAA and equivalent) thanks to the status of preferred creditor and the existence of callable capital.

The Standoff

The structure of MDBs discussed above explains why the western block which controls the global MDBs is cautious about a change in the preferred creditor status.

Recently, as reported by the Financial Times, a group of developing economies issued an internal note that stated, “The World Bank’s high rating was necessary to be able to raise funds at a cost that would enable lending at below-market rates. This is the very rationale underlying the [multilateral development bank] concept.”

“The note was signed by countries including Brazil, Argentina, Chile and Peru in South America, as well as by Pakistan, Iran, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, India, Indonesia, Singapore, Vietnam, China, Saudi Arabia and Russia, plus Egypt and more than two dozen African nations.”

When considering Beijing's seemingly conflicting stance, it is important to acknowledge that there are multiple Chinese creditors. This is because China's Finance, Trade, and Foreign Ministries, Central Bank, and National Development Agency each have separate and occasionally divergent mandates and objectives.

Furthermore, China is aware that any debt forgiveness on the part of multilateral institutions would be financed by the investment incomes of the MDBs and additional funding from its donor countries, which would have a direct financial impact on the Paris Club and the Western Bloc.

In light of this, it seems the stalemate is likely to remain in place, though the rise of China and other nations as global lenders is likely to spur a shift in the existing restructuring frameworks and the status of Multilateral organizations. Establishing an agreement will be tough, but potential solutions have been floated.

At the G20 meetings last year, a report was tabled that suggested five steps to assist the MDBs: (1) adapt the approach to defining risk tolerance, (2) give greater consideration to callable capital, (3) make use of financial innovations, (4) improve CRAs' assessment of MDB financial strength, and (5) increase access to MDB data and analysis.