“Chai?”

That was how the conversation around Tony's book always began. And in a matter of seconds, our friendship changed to that of a writer and an editor. And what a literary journey we undertook together!

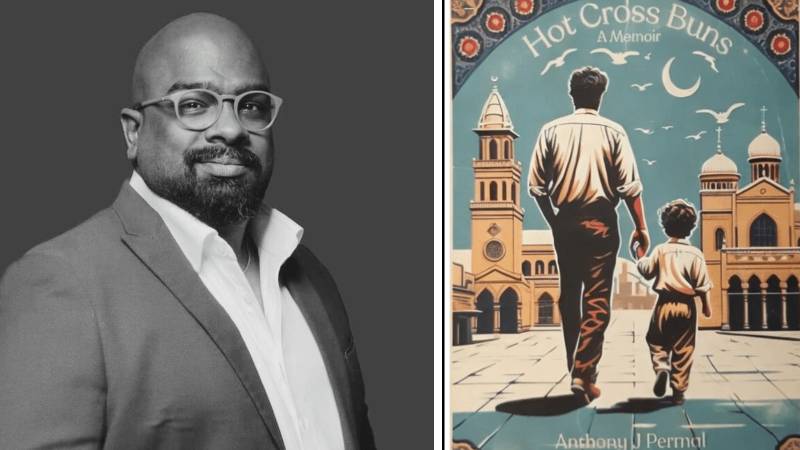

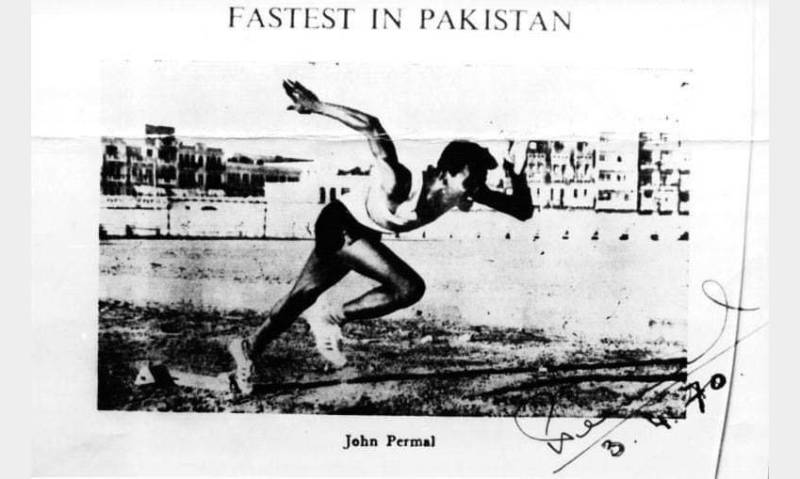

Anthony Jude Permal, affectionately known as Tony by his friends and family, had reached out to me in 2022 about his book. "This is my memoir, but it's also about my dad," he would say. He always stressed on the point about the book being about his father first and then his memoir. Tony could never stop talking about his father, the late John Permal, who was the fastest man in Pakistan and represented the country at the 1972 Munich Olympics and the Asian Games in 1966 and 1970. At times, it felt that one knew John Permal more than one knew Tony. The stories of his athleticism, his beautiful hair, his love for running. Many ordinary anecdotes were made extraordinary as they were narrated through the perspective of a man who adored his father immensely.

Tony always spoke excitedly about his book. "I just want to tell my story, that's all." Numerous attempts at finding a literary agent came to nothing despite the international publishing push for Black, Indigenous, (and) People of Colour (BIPOC) to ensure diversity and inclusion. One fine day, in the midst of my own personal chaos while the draft was being prepared, when Tony swooped in as a saviour and I found myself looking at a manuscript titled 'Hot Cross Buns' (a reference to the famous buns made by a particular bakery in Karachi on Easter).

There's a sense of necessity for a coping mechanism during times of trouble, and this book came at a time when I needed something to stay hopeful. Night after night, I would open the manuscript, hear Tony's voice in my mind and escape my own reality to his fascinating world.

From discovering the Bee Gees in Saudi Arabia to being overwhelmed with joy when the Permals got their first home - Tony's story is where I began to find my own sense of home. When he had a supernatural experience in his new home and ran to his parent's room, I, too, began to find refuge in his story. It is written through the eyes of an innocent child, untouched by the grotesqueness of anti-minority hatred. Hot Cross Buns is a jewel of a book that holds a piece of Pakistan that really ought to be cherished and loved as a reminder for the need to uphold humanity above all else.

Another history lesson that gave the little boy a sense of pride in being a Pakistani was regarding the name of the street where he grew up

From going to the Jamaat Khana area and eating at the various delectable eateries there such as Baloch Ice Cream and the Indian snack food joint Thali Land, Tony reminisces a gorgeous and forgotten chunk of Pakistani history. His aim is to paint an authentic picture of what Karachi was like in the pre-Zia era, perfectly capturing the spirit of what the country was and should have been like today.

The spirit of that era really comes alive when Tony delves into how the Christmas Star tradition began in Pakistan. It is a marvellous story of building the biggest Christian star in the country, a way of living that is no longer present. It is heartbreaking when he ends the chapter with: "I wonder if this unbelievable Christmas story, so unique to Pakistan, will ever be told beyond these pages: a story of 50 families, Hindus and Muslims and Parsis and Christians, coming together to showcase what made Karachi great."

The most remarkable aspect of the book is how the historical documentation goes hand in hand with Tony's story. There is one endearing episode about moving to Faria apartments, where he was told by his mother that from now on, they would attend Mass at St Lawrence's Catholic Church. During one of the walks to the church, little Tony notices a mosque on the road and enquires about it. He is told it is Pakola Masjid (original name being Ghafooria Masjid), and in response, the little boy innocently asks why the mosque is named after his favourite drink. Tony writes with a sense of pride in being a Pakistani, a sentiment that is fast-disappearing in not just the minorities but the majority population as well. In one of the chapters, he narrates how, after Mass, he was greeted by some of his father's friends at home. They would tell him exciting stories about Soldier Bazaar and the residence of GM Syed – though their residence was in a Catholic-majority area, it was also one of the most important political districts in Pakistan. It was through these stories that Tony was infused with a sense of nationhood: "Did you know the Pakistan Resolution was written right here in Soldier Bazaar in 1943?", Uncle Eddie asked Tony.

Another history lesson that gave the little boy a sense of pride in being a Pakistani was regarding the name of the street where he grew up, Manekjee Street. Manekjee Dastoor Dhala was a Parsi who went to Columbia University and was supported financially by the Indian business family, the Tata Group:

"The street was named after him in honour of his position as the only High Priest of Zoroastrianism in Karachi… Due to the street's prominence, numerous influential families relocated there representing a diverse range of religions."

Tony then goes on to map the diverse communities living peacefully side by side, from the Al Karam scions to the Ismailis - under the shade of one of their Jamaat Khanas (community centre), one could find a variety of 'mom and pop shops' offering a variety of cuisines such as Indian snacks, Chinese food and Peshawari ice cream that lined the road all the way down to Cincinnatus Town.

"Cincinnatus Town, which had one of the largest shia populations in Pakistan… Catholics and Shias lived in Cincinnatus Town peacefully for decades. It's why the area is lovingly called Catholic Colony, even by the Shias."

There is something curious about the perspective that Tony provides on the Zia era. Given the current state of affairs, tracing the blood trail to one man is effective in understanding the country's trajectory

Close to becoming a teenager, as little Tony navigated the wondrous world of Karachi with its mosaic of communities living on streets named after Goan Catholics, he discovered Pakistani music on television called "Gold Leaf Rhythm Wythm" and a record store called "Virgil" where he was introduced to mixed tapes and how useful they were in wooing a particular young lady.

There is something curious about the perspective that Tony provides on the Zia era. Given the current state of affairs, tracing the blood trail to one man is effective in understanding the country's trajectory, it is also necessary to understand the setting within which such a main character operated with so much impunity.

"For some reason everyone talked about this man called Zi-something… He ran the country and according to people on the news, he always flew around the world getting people to help us."

This is where the tenderness with which Tony writes about Karachi hurts. The innocence of a way of life that is unlikely to be witnessed in Pakistan again, the loss of that openness and acceptance cuts through the pages. "I didn't realise so many people hated him this much because it seemed like a birthday party instead of the day someone died. I thought we were supposed to be sad for people who died."

Tony also shares the glorious return of Benazir Bhutto (BB), which may have been a scream in the abyss, in the most poignant way. Looking at that moment today, that shining beacon of hope in the form of BB makes one understand how soul-crushing reading history must be and it is not any wonder why history beyond the realm of politics is not readily consumed - the heaviness of the loss of hope is never easy to accept. "Rizwana piped in to tell me how Benazir Bhutto… was the new hope of the country, and of women everywhere…"

With the entry of the MQM, a new dimension of political activity opens up in Karachi which leads Catholics to move into other areas. In an exchange with a shopkeeper to get Tony's bicycle fixed, his mother faces a challenge when she asks why it is so expensive: "Dekho Madam, we have to make our own profit and we also have to make sure the Party gets its profits otherwise we'll be put out of business."

As it turns out not many Catholics could afford this new 'tax' and a whole cultural shift takes place as seeds of intolerance take root.

"Years ago young parishioners from St Lawrence's would walk… sing Christmas Carols… At this moment, they were not allowed to do that anymore… Muslims in the buildings didn't like that."

This book is more than Anthony's memories or an homage to his father, John Permal. It is a documentation of Pakistan's lost history and soul that ought to be part of the mainstream conversations

There is at least one turning point in everyone's lives, if not multiple. The demolition of Babri Masjid (December, 1992) was a turning point for a generation of Pakistani Christians, especially those living in Karachi. The attack on a Christian place of worship in the wake of the Babri Masjid incident proved to be the culmination of the simmering poison of prejudice and religious extremism, that had been unleashed on the country during Zia. As Tony writes:

"We were Catholic, and we were in Pakistan, miles away from India. What did any of this have to do with us?"

Apparently, it had a lot to do with them. After all, why would a place of worship be destroyed by 'well-wishing' Muslims? Yet, damage was done to Sacred Heart Church: "The gates to the church courtyard had been mangled… The churchyard was filled with scattered debris… shattered construction blocks, bricks and mud from the garden where someone had attempted to uproot and ruin the flowers… ground was scattered with shattered statues of Jesus, Mother Mary, the Sacred Heart statue, St Joseph and Baby Jesus… stomped on with great force leaving them completely crushed… the altar was a mess… tablecloth blessed by the bishop had been ripped and torn… the podium where the statues previously stood had been hacked away with axes."

Yet, somehow, the Tabernacle, which houses the sacred bread and wine, remained intact. And it is truly humbling when the parish priest tell these innocent children in the middle of all this destruction: "Love could not be destroyed by hate." This is where Tony refers to himself as being two - one Anthony from pre-Babri Masjid atrocity and another Anthony from after the incident.

This book is more than Anthony's memories or an homage to his father, John Permal. It is a documentation of Pakistan's lost history and soul that ought to be part of the mainstream conversations. As blasphemy cases rise, as more and more losses are incurred in the form of human lives, cultural heritage and history lost, Pakistan is on the losing end in the battle against religious extremism and intolerance. It took one Christian Pakistani to question why his faith did not have a home in his home country, how long before the rest of us question our presence?

"We believed in the Abrahamic God. Somehow, we went from 'People of the Book' to 'people to be booked' in prison. Dad spoke to me at length… "You can't trust anyone in Pakistan anymore. They ratified the blasphemy laws this year, and one wrong word can send you to jail, or worse… They can't prove it, and they don't need to. It's our word against theirs."

Word. That is what it came down to when writing this book. For Tony, the written word was all he had left, and thus, he wrote his own legacy.

Anthony Jude Permal tragically passed away on August 18th 2024.

On August 29th 2024, a posthumous book launch of 'Hot Cross Buns' took place in Dubai.