Perhaps the best way to start an analysis of the subject is to offer a quote from our Prime Minister who told the American news agency Bloomberg in an interview in Karachi last Saturday that, “the military strategy in Afghanistan has not worked and it will not work…There has to be a ‘political settlement, … That’s the bottom-line.”

In the same interview the Prime Minister also reportedly said that while the government supports the war against terror, it won’t let the war in Afghanistan spill into Pakistan—a sentiment shared by our army chief who said virtually the same thing in the meeting of the Quadrilateral Cooperation and Coordination Mechanism in Dushanbe. This mechanism, which is perhaps the only Afghanistan-related forum for military leaders from the region, brings them together from Afghanistan, China, Pakistan and Tajikistan to devise and implement counter-terrorism strategies.

These statements of policy are, to my mind, eminently sensible ones and should we look at them seriously, appear to be entirely compatible with what the Americans are demanding, albeit with an arrogance that grates. It is true that this is what you see in the Trump speech, along with an emphasis on “winning” and casting doubts on the prospects for reconciliation. It is, however, clear that when it comes to implementation, the meaning of Trump’s declaration will be what the Mattis/Master/Kelly trio on the one hand and Tillerson on the other interpret it to be.

Interpreting the US

This interpretation is clear from the short statement Secretary of State Rex Tillerson put out immediately after Trump’s speech and then in the elaboration he offered in a lengthy press briefing where he said, “the President was clear… this entire effort is intended to put pressure on the Taliban to have the Taliban understand: You will not win a battlefield victory. We may not win one, but neither will you. And so at some point we have to come to the negotiating table and find a way to bring this to an end.”

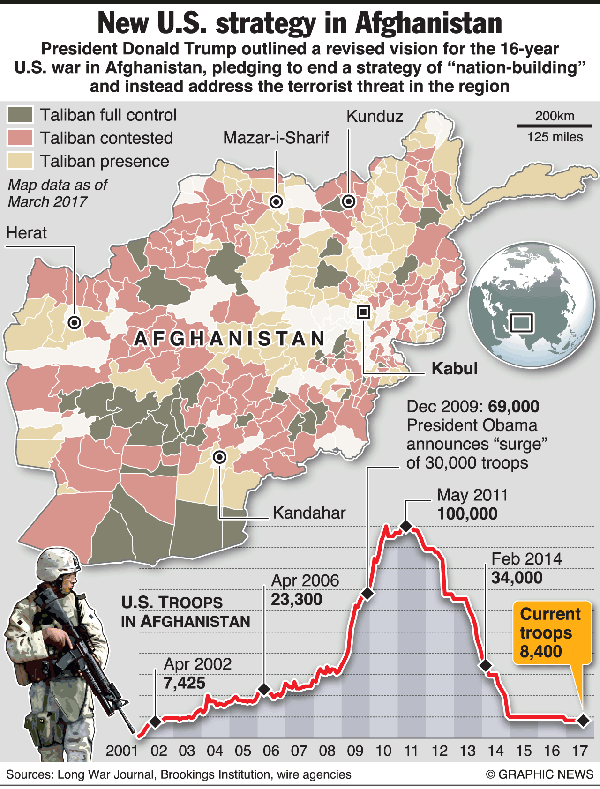

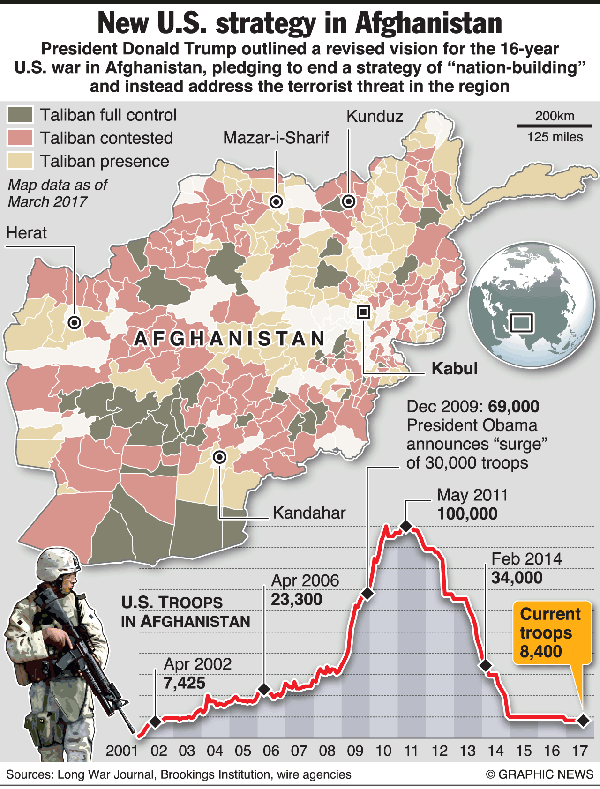

We may, as good conspiracy theorists abundantly available in Pakistan do, suggest that this is a mere cover for the US desire to justify their permanent presence in Afghanistan. If, however, we abandon such thinking, we would see that this is supported by what is actually being done or being planned. Trump’s three principal advisers, all military men with Afghanistan experience, are advocating or accepting a troop increase of some 4,000 personnel. This is not the number any military man would say is enough for a military victory. It may suffice to deny the Taliban victory and be enough to provide an increased level of training to the Afghan National Defence Security Forces. This may enable them to hold the Taliban at bay but is certainly not enough to ensure victory unless the Taliban are starved of their source of support. Tillerson was not alone in making reconciliation a theme. Remarks Defense Secretary James Mattis had made earlier talked of reconciliation being the key and reconciliation was again the focus in Gen. John Nicholson’s recent interview which attracted our attention, largely because of what he said about Taliban sanctuaries in Pakistan.

We should, therefore, accept that the US, even under the unpredictable President Trump, is looking for reconciliation as the means by which it can make an honourable exit from Afghanistan and ensure that it does not become a safe haven for terrorists wishing to attack the United States or its allies.

Prospects & reality

Things that have happened in the past may give us reason for scepticism. It was only after they had been in Afghanistan for 10 long years that then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton spoke, in February 2011, of the Taliban renunciation of ties with Al-Qaeda and the acceptance of the Afghan Constitution as the desired outcome of talks with the Taliban rather than a pre-condition. Then they worked hard with the Qataris to help set up an office in Doha for Taliban representatives and sought and secured our cooperation in getting Taliban with acceptable credentials to man that office—Tayyab Agha had worked as Mullah Umar’s private secretary and was considered his confidante. They even managed to persuade the powers in the Taliban structure and in Pakistan that these representatives could take their families with them.

For reasons that I will elaborate upon later, the only thing that the Americans achieved from all the effort that they put into the setting up the Qatar office (which continues to exist) was secure the release from Taliban custody of the one American soldier, Bowe Bergdahl, who the Taliban had captured in May 2014 in exchange for five of their men. These five men were to be kept in Qatar under the custody of the Qatari authorities and are still there. It was said at that time that they were Taliban of influence and could hopefully be persuaded to help with reconciliation.

While the Americans can say that the Taliban’s public statements seem to close the door on reconciliation talks, the fact is that in the past the Taliban lost no opportunity to interact with government representatives, justifying this as a means of explaining their point of view. In my view, the true obstacle to reconciliation talks was not Taliban obduracy but President Karzai. He referred often to the Taliban as “brothers” but he feared that any advance in granting them a measure of legitimacy would undercut his position. This is the conclusion one reaches after studying the series of events recounted below.

Sincerity

Earlier, in September 2011, former President Burhanuddin Rabbani, then the head of the 70-member High Peace Council set up by President Karzai, was assassinated by an unknown suicide bomber. This attack was claimed by the Taliban and dealt a serious blow to the cause of promoting dialogue. I do believe that Professor Rabbani was genuinely committed to reconciliation but he had to take Karzai’s predilections into account. This explains the fact that Rabbani cut short his stay in Tehran to return to meet this assailant, who was, by Rabbani’s aides, particularly senior adviser Masoom Stanakzai, considered to be a genuine Taliban representative who was going to offer substantive negotiations. However, on the other hand, while Rabbani was in Tehran attending a religious conference in which there were Taliban participants of some status in the movement, there were no reports that he sought to establish contact with them.

In 2012, his son and successor as head of the High Peace Council Salahuddin Rabbani drafted a document titled, “Peace Process Roadmap to 2015” and apparently shared it with the Pakistani authorities. It envisaged an important role for Pakistan in persuading the Taliban to talk, agree to a ceasefire and allow free movement for humanitarian services. The key in this proposal was the commitment that, “The negotiating parties to agree on modalities for the inclusion of Taliban and other armed opposition leaders in the power structure of the state, to include non-elected positions at different levels with due consideration of legal and governance principles.” This meant that you brought the Taliban into the government in unelected offices after which they would become a mainstream political party that could fight elections.

This roadmap was well publicised when it was first revealed by an American news agency but then it mysteriously died out with no explanation publicly offered. There was speculation that Karzai felt that this gave away too much to the Taliban. Many commentators felt that this was not really doable but nobody in my view made a convincing case against what to my mind was the logical way to advance reconciliation.

As the date for the US withdrawal in 2014 drew closer there were greater efforts towards promoting an Afghan-owned and -led political process. The UN got into the act, trying to organise a conference in Turkmenistan at which government representatives were to interact with the Taliban and Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. This proposal was shot down by Karzai in February 2013, apparently because he feared that there was some conspiracy to give the Taliban and Hekmatyar greater legitimacy than he was prepared to accord them.

Now there is a government in Kabul which has brought Hekmatyar back to the centre of power. They have had his name, with American and Western cooperation, removed from the UN sanctions list and he is free to engage in whatever activity he chooses in Afghanistan. There is great resentment of Hekmatyar among moderate Afghans. They see him quite rightly as the man who, while theoretically being the Prime Minister of Afghanistan, bombarded Kabul and wreaked more damage than had been done to that city by a decade of Soviet occupation. There can be, in my view, no better evidence of the sincerity with which President Ghani and Chief Executive Abdullah Abdullah are prepared to pursue reconciliation.

President Ghani has asked the Taliban to open an office in Afghanistan to conduct these negotiations. It is obvious that the international community will have to guarantee the security of the personnel deputed by the Taliban to this office but this would be a step in the right direction towards which all parties concerned should push the Taliban.

Afghan reality

It would be wise as we considered the changes this will necessitate in our policies to look also at the situation in Afghanistan. Today the ANDSF is about 352,000 strong. It is financed by the Americans to the tune of $4.1 billion annually. The Afghans are supposed to contribute $500 million towards this cost but I don’t think they can do it. The Afghan budget, even while President Ghani has had some limited success in improving tax and customs revenues, is dependent about 63% on foreign assistance. Today unemployment is at 40%. The opium production of 4,800 tons is valued at about two-thirds of the total agricultural produce and about 16% of the Afghan GDP.

Were there to be an American withdrawal and with it, as a logical consequence, the cessation of assistance ($15 billion for 2017-2020 was pledged as economic assistance at the Brussels Conference in October 2016) the ANDSF would have to be demobilised, putting on the streets this vast body of men who have no skills beyond the handling of weapons. All health and education establishments would be left bereft of salaries for staff. One cannot visualise this shortfall being met by a regional effort. Economic refugees would stream across the only porous border, and that is Pakistan.

We must know that at the moment the legal exploitation of Afghanistan’s mineral resources estimated at about $1 trillion is almost non-existent. Illegal mining yields revenues estimated at about $100 million for the Taliban and a like amount for corrupt Afghan officials. Two projects (Aynak Copper Mine and Hajigak Iron Ore) are being renegotiated or have been abandoned for the time being. The renegotiation is not because of the security situation but because its conception was apparently overly optimistic. In my view, it would take at least ten years or more to create the conditions in which Afghanistan’s mineral wealth can be properly exploited. Trump’s dreams of harnessing Afghan mineral wealth to compensate the US is for the time being a pipe dream. It does, however, have the potential a decade or more down the road to enhance Pak-Afghan economic cooperation as Pakistan becomes the venue for the processing and transportation to market of Afghan minerals. We could even think of joint projects such as the setting up of a smelter to refine the copper ore produced in Aynak and Reko Diq, thus overcoming the problem that neither is said to produce enough to justify a smelter on its own.

It is, of course, true as we look at the possibility of reconciliation talks that there are many factions now among Taliban ranks and some of them are opposed to reconciliation. It is also true that there are many powerful figures in the administrative and political structures of the Afghan National Unity government that are opposed to reconciliation. Perhaps this is overly cynical, but in my view, money not ideology is the reason for opposition on both sides. The process is therefore going to be long and will need deft and cooperative diplomacy on the part of the parties that need reconciliation, chief among them the governments of Afghanistan and Pakistan.

In Pakistan

Umbrage in official circles in Pakistan about the tone of President Trump’s speech is understandable but we have to go beyond that. If all centres of power in Pakistan are agreed that reconciliation offers the best chance for peace in Afghanistan, then we must do what we can to promote this. If the Prime Minister and the COAS both say that they do not want to allow Afghanistan’s war to be fought on Pakistan’s soil, then it would be logical to remove from Pakistan those elements that can bring this about.

Finding other friends in the region is a good step but this cannot be a substitute for talking to the principal player and seeking out areas of convergence while trying to minimise divergences. We should see that the “friends” we are courting all advocate talks. This is the urgent task for our diplomacy. It must be undertaken after a cold-blooded unemotional analysis of the current situation and a determination of what would best serve Pakistan’s interests. Our officials should meet the Americans bilaterally and in the Quadrilateral Coordination Group, which needs to be reactivated.

1996: Taliban capture Kabul. UN envoy arrives, says Taliban willing to work for peace.

1997: Peace talks are held in Islamabad between Taliban and Opposition forces but no progress made. Taliban delegation meets Robin Raphel in US.

1998: US Ambassador to the UN visits Kabul to ask Taliban to attend talks and discuss bin Laden. No results.

1999: UN-sponsored talks between Taliban and Northern Alliance break down. UN Security Council imposes sanctions on Taliban.

2000: US wins UN support for tougher sanctions against Taliban, including a freeze on overseas assets.

2001: US demands extradition of Osama bin Laden for September 11. Taliban refuse. US, allies begin bombing. US-backed Northern Alliance capture Kabul, rest of country falls.

2008: Senior ex-Taliban attempt to mediate talks between insurgents and Kabul, traveling between Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and European capitals.

2009: Senior ex-Taliban official says he and others have contacted Taliban chief Mullah Omar in a bid for peace talks. He says both exchanged demands.

2010: Petraeus and McChrystal hold out possibility of eventual talks. Taliban ally Gulbuddin Hekmatyar says setting timetable for withdrawal of foreign troops may help. Taliban reiterate that withdrawal only solution. Taliban say they will not enter talks as long as foreign troops in country. (Reuters)

The writer heads the Global and Regional Studies Centre at IoBM, a Karachi-based university. He is a former foreign secretary and has served as ambassador to the US and Iran. He lectures at NDU and has written extensively on Pakistan and international relations

In the same interview the Prime Minister also reportedly said that while the government supports the war against terror, it won’t let the war in Afghanistan spill into Pakistan—a sentiment shared by our army chief who said virtually the same thing in the meeting of the Quadrilateral Cooperation and Coordination Mechanism in Dushanbe. This mechanism, which is perhaps the only Afghanistan-related forum for military leaders from the region, brings them together from Afghanistan, China, Pakistan and Tajikistan to devise and implement counter-terrorism strategies.

These statements of policy are, to my mind, eminently sensible ones and should we look at them seriously, appear to be entirely compatible with what the Americans are demanding, albeit with an arrogance that grates. It is true that this is what you see in the Trump speech, along with an emphasis on “winning” and casting doubts on the prospects for reconciliation. It is, however, clear that when it comes to implementation, the meaning of Trump’s declaration will be what the Mattis/Master/Kelly trio on the one hand and Tillerson on the other interpret it to be.

Given statements by Tillerson, Mattis and Nicholson, we should accept that the US, even under the unpredictable President Trump, is looking for reconciliation as the way to honourably exit from Afghanistan and ensure that it does not become a safe haven for terrorists

Interpreting the US

This interpretation is clear from the short statement Secretary of State Rex Tillerson put out immediately after Trump’s speech and then in the elaboration he offered in a lengthy press briefing where he said, “the President was clear… this entire effort is intended to put pressure on the Taliban to have the Taliban understand: You will not win a battlefield victory. We may not win one, but neither will you. And so at some point we have to come to the negotiating table and find a way to bring this to an end.”

We may, as good conspiracy theorists abundantly available in Pakistan do, suggest that this is a mere cover for the US desire to justify their permanent presence in Afghanistan. If, however, we abandon such thinking, we would see that this is supported by what is actually being done or being planned. Trump’s three principal advisers, all military men with Afghanistan experience, are advocating or accepting a troop increase of some 4,000 personnel. This is not the number any military man would say is enough for a military victory. It may suffice to deny the Taliban victory and be enough to provide an increased level of training to the Afghan National Defence Security Forces. This may enable them to hold the Taliban at bay but is certainly not enough to ensure victory unless the Taliban are starved of their source of support. Tillerson was not alone in making reconciliation a theme. Remarks Defense Secretary James Mattis had made earlier talked of reconciliation being the key and reconciliation was again the focus in Gen. John Nicholson’s recent interview which attracted our attention, largely because of what he said about Taliban sanctuaries in Pakistan.

We should, therefore, accept that the US, even under the unpredictable President Trump, is looking for reconciliation as the means by which it can make an honourable exit from Afghanistan and ensure that it does not become a safe haven for terrorists wishing to attack the United States or its allies.

Prospects & reality

Things that have happened in the past may give us reason for scepticism. It was only after they had been in Afghanistan for 10 long years that then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton spoke, in February 2011, of the Taliban renunciation of ties with Al-Qaeda and the acceptance of the Afghan Constitution as the desired outcome of talks with the Taliban rather than a pre-condition. Then they worked hard with the Qataris to help set up an office in Doha for Taliban representatives and sought and secured our cooperation in getting Taliban with acceptable credentials to man that office—Tayyab Agha had worked as Mullah Umar’s private secretary and was considered his confidante. They even managed to persuade the powers in the Taliban structure and in Pakistan that these representatives could take their families with them.

For reasons that I will elaborate upon later, the only thing that the Americans achieved from all the effort that they put into the setting up the Qatar office (which continues to exist) was secure the release from Taliban custody of the one American soldier, Bowe Bergdahl, who the Taliban had captured in May 2014 in exchange for five of their men. These five men were to be kept in Qatar under the custody of the Qatari authorities and are still there. It was said at that time that they were Taliban of influence and could hopefully be persuaded to help with reconciliation.

While the Americans can say that the Taliban’s public statements seem to close the door on reconciliation talks, the fact is that in the past the Taliban lost no opportunity to interact with government representatives, justifying this as a means of explaining their point of view. In my view, the true obstacle to reconciliation talks was not Taliban obduracy but President Karzai. He referred often to the Taliban as “brothers” but he feared that any advance in granting them a measure of legitimacy would undercut his position. This is the conclusion one reaches after studying the series of events recounted below.

Sincerity

Earlier, in September 2011, former President Burhanuddin Rabbani, then the head of the 70-member High Peace Council set up by President Karzai, was assassinated by an unknown suicide bomber. This attack was claimed by the Taliban and dealt a serious blow to the cause of promoting dialogue. I do believe that Professor Rabbani was genuinely committed to reconciliation but he had to take Karzai’s predilections into account. This explains the fact that Rabbani cut short his stay in Tehran to return to meet this assailant, who was, by Rabbani’s aides, particularly senior adviser Masoom Stanakzai, considered to be a genuine Taliban representative who was going to offer substantive negotiations. However, on the other hand, while Rabbani was in Tehran attending a religious conference in which there were Taliban participants of some status in the movement, there were no reports that he sought to establish contact with them.

In 2012, his son and successor as head of the High Peace Council Salahuddin Rabbani drafted a document titled, “Peace Process Roadmap to 2015” and apparently shared it with the Pakistani authorities. It envisaged an important role for Pakistan in persuading the Taliban to talk, agree to a ceasefire and allow free movement for humanitarian services. The key in this proposal was the commitment that, “The negotiating parties to agree on modalities for the inclusion of Taliban and other armed opposition leaders in the power structure of the state, to include non-elected positions at different levels with due consideration of legal and governance principles.” This meant that you brought the Taliban into the government in unelected offices after which they would become a mainstream political party that could fight elections.

This roadmap was well publicised when it was first revealed by an American news agency but then it mysteriously died out with no explanation publicly offered. There was speculation that Karzai felt that this gave away too much to the Taliban. Many commentators felt that this was not really doable but nobody in my view made a convincing case against what to my mind was the logical way to advance reconciliation.

As the date for the US withdrawal in 2014 drew closer there were greater efforts towards promoting an Afghan-owned and -led political process. The UN got into the act, trying to organise a conference in Turkmenistan at which government representatives were to interact with the Taliban and Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. This proposal was shot down by Karzai in February 2013, apparently because he feared that there was some conspiracy to give the Taliban and Hekmatyar greater legitimacy than he was prepared to accord them.

Now there is a government in Kabul which has brought Hekmatyar back to the centre of power. They have had his name, with American and Western cooperation, removed from the UN sanctions list and he is free to engage in whatever activity he chooses in Afghanistan. There is great resentment of Hekmatyar among moderate Afghans. They see him quite rightly as the man who, while theoretically being the Prime Minister of Afghanistan, bombarded Kabul and wreaked more damage than had been done to that city by a decade of Soviet occupation. There can be, in my view, no better evidence of the sincerity with which President Ghani and Chief Executive Abdullah Abdullah are prepared to pursue reconciliation.

President Ghani has asked the Taliban to open an office in Afghanistan to conduct these negotiations. It is obvious that the international community will have to guarantee the security of the personnel deputed by the Taliban to this office but this would be a step in the right direction towards which all parties concerned should push the Taliban.

Afghan reality

It would be wise as we considered the changes this will necessitate in our policies to look also at the situation in Afghanistan. Today the ANDSF is about 352,000 strong. It is financed by the Americans to the tune of $4.1 billion annually. The Afghans are supposed to contribute $500 million towards this cost but I don’t think they can do it. The Afghan budget, even while President Ghani has had some limited success in improving tax and customs revenues, is dependent about 63% on foreign assistance. Today unemployment is at 40%. The opium production of 4,800 tons is valued at about two-thirds of the total agricultural produce and about 16% of the Afghan GDP.

Were there to be an American withdrawal and with it, as a logical consequence, the cessation of assistance ($15 billion for 2017-2020 was pledged as economic assistance at the Brussels Conference in October 2016) the ANDSF would have to be demobilised, putting on the streets this vast body of men who have no skills beyond the handling of weapons. All health and education establishments would be left bereft of salaries for staff. One cannot visualise this shortfall being met by a regional effort. Economic refugees would stream across the only porous border, and that is Pakistan.

We must know that at the moment the legal exploitation of Afghanistan’s mineral resources estimated at about $1 trillion is almost non-existent. Illegal mining yields revenues estimated at about $100 million for the Taliban and a like amount for corrupt Afghan officials. Two projects (Aynak Copper Mine and Hajigak Iron Ore) are being renegotiated or have been abandoned for the time being. The renegotiation is not because of the security situation but because its conception was apparently overly optimistic. In my view, it would take at least ten years or more to create the conditions in which Afghanistan’s mineral wealth can be properly exploited. Trump’s dreams of harnessing Afghan mineral wealth to compensate the US is for the time being a pipe dream. It does, however, have the potential a decade or more down the road to enhance Pak-Afghan economic cooperation as Pakistan becomes the venue for the processing and transportation to market of Afghan minerals. We could even think of joint projects such as the setting up of a smelter to refine the copper ore produced in Aynak and Reko Diq, thus overcoming the problem that neither is said to produce enough to justify a smelter on its own.

It is, of course, true as we look at the possibility of reconciliation talks that there are many factions now among Taliban ranks and some of them are opposed to reconciliation. It is also true that there are many powerful figures in the administrative and political structures of the Afghan National Unity government that are opposed to reconciliation. Perhaps this is overly cynical, but in my view, money not ideology is the reason for opposition on both sides. The process is therefore going to be long and will need deft and cooperative diplomacy on the part of the parties that need reconciliation, chief among them the governments of Afghanistan and Pakistan.

In Pakistan

Umbrage in official circles in Pakistan about the tone of President Trump’s speech is understandable but we have to go beyond that. If all centres of power in Pakistan are agreed that reconciliation offers the best chance for peace in Afghanistan, then we must do what we can to promote this. If the Prime Minister and the COAS both say that they do not want to allow Afghanistan’s war to be fought on Pakistan’s soil, then it would be logical to remove from Pakistan those elements that can bring this about.

Finding other friends in the region is a good step but this cannot be a substitute for talking to the principal player and seeking out areas of convergence while trying to minimise divergences. We should see that the “friends” we are courting all advocate talks. This is the urgent task for our diplomacy. It must be undertaken after a cold-blooded unemotional analysis of the current situation and a determination of what would best serve Pakistan’s interests. Our officials should meet the Americans bilaterally and in the Quadrilateral Coordination Group, which needs to be reactivated.

Timeline of talks

1996: Taliban capture Kabul. UN envoy arrives, says Taliban willing to work for peace.

1997: Peace talks are held in Islamabad between Taliban and Opposition forces but no progress made. Taliban delegation meets Robin Raphel in US.

1998: US Ambassador to the UN visits Kabul to ask Taliban to attend talks and discuss bin Laden. No results.

1999: UN-sponsored talks between Taliban and Northern Alliance break down. UN Security Council imposes sanctions on Taliban.

2000: US wins UN support for tougher sanctions against Taliban, including a freeze on overseas assets.

2001: US demands extradition of Osama bin Laden for September 11. Taliban refuse. US, allies begin bombing. US-backed Northern Alliance capture Kabul, rest of country falls.

2008: Senior ex-Taliban attempt to mediate talks between insurgents and Kabul, traveling between Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and European capitals.

2009: Senior ex-Taliban official says he and others have contacted Taliban chief Mullah Omar in a bid for peace talks. He says both exchanged demands.

2010: Petraeus and McChrystal hold out possibility of eventual talks. Taliban ally Gulbuddin Hekmatyar says setting timetable for withdrawal of foreign troops may help. Taliban reiterate that withdrawal only solution. Taliban say they will not enter talks as long as foreign troops in country. (Reuters)

The writer heads the Global and Regional Studies Centre at IoBM, a Karachi-based university. He is a former foreign secretary and has served as ambassador to the US and Iran. He lectures at NDU and has written extensively on Pakistan and international relations