Sindh’s multi-caste-based-village presents a complex social landscape where a harmonious surface often conceals a contradictory underbelly. A typology of Sindh’s villages can be defined along various parameters, but in this article, I focus specifically on villages characterised by a mix of surnames and castes, which I refer to as multi-caste-based villages. However, it is important to clarify that a surname identifies individuals as part of a particular lineage, while caste refers to a social stratification system—a hierarchical classification based on occupation and social status. The term multi-caste-based village reflects the coexistence of multiple surnames and castes, acknowledging that in rural Sindh, these identifiers, be they surnames or castes, are closely tied to social identity and cultural heritage.

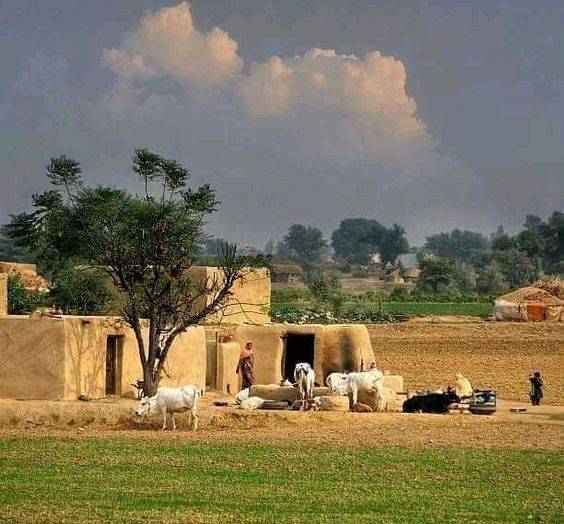

Drawing from my extensive experience with village development programs, I observe that the rural population of significantly large villages in Sindh typically falls into two broad categories: those engaged in agriculture and those belonging to the service provider or non-agricultural group. Across northern Sindh, particularly on the left bank of the River Indus, caste serves as a fundamental clue for social stratification, delineating specific roles rituals, and responsibilities. These social groups are often interdependent, with their economic activities linked to one another, making it evident how caste shapes the hierarchical organisation of village life.

My field notes reveal that the multi-caste-based village often unites during times of disaster, or an attack. In such situations villagers act as cohesive unit. This solidarity was notably observed during the devastating floods in Sindh. In these crises, individuals from various castes came together to provide mutual assistance, demonstrating that shared adversity can transcend traditional divisions.

Another critical situation that fosters unity is when the village faces external threats, whether from neighbouring villages or criminal elements. Numerous instances document how villages coalesce in the face of such challenges, embodying a collective identity that rises above caste affiliations. Additionally, the preservation of a village's honour—especially in cases of perceived injustices or attacks on women—serves as a powerful motivator for collective action. Such moments of unity reflect a deep-seated recognition that, despite their differences, the well-being of the village as a whole is paramount.

Beyond these urgent circumstances, several everyday interactions bridge the micro-faults among the inhabitants. For instance, when landholders and farmers of different castes share a common watercourse for irrigation, a sense of social coherence emerges. This shared resource fosters collaboration and mutual respect, as individuals rely on one another for their livelihoods. Similarly, a village school served as melting pots where children from diverse castes sit side by side, forging friendships that gradually diminish caste-related gaps. These early social interactions can lay the groundwork for future cooperation and understanding. Shared communal spaces, such as mosques and temples, also contribute to mending social divisions, as they provide venues for joint religious and cultural activities. Moreover, public facilities like bus stops and hospitals offer plural venues for interaction, fostering connections across caste lines and facilitating the sharing of experiences.

In multi-caste-based villages, marriages predominantly occur within one’s caste, with cross-caste unions remaining rare

Political engagement emerges as one of the most effective ways to bridge caste divisions. Villages with active units of nationalist parties such as the Jeay Sindh Mahaz, or organisations focused on class struggle like the Sindh Hari Committee, tend to experience less division based on caste. My observations indicate that authentic political work and genuine social movements serve as critical cementing forces in fragmented villages. When villagers come together to advocate for common goals, they often find common ground that transcends caste lines, reinforcing a collective identity rooted in shared aspirations.

Despite these unifying forces, there are persistent divisions rooted in the caste system. One prominent challenge is the micro-settlement structure within the multi-caste-village, often delineated into Paras (lanes) associated with specific castes or surnames—such as Hingoran Jo Paro, Junejan Jo Paro, Mangian Jo Paro, Abasian Jo Paro, and Bughian Jo Paro. These Paras establish invisible boundaries—geographical, social, and emotional— and these limits reinforce caste identities. Each lane fosters its own micro-culture, with distinct customs and practices that underline the differences among castes. The construction of multiple mosques or Imambargahs within the same village often serves as a visible assertion of this ‘otherness.’ These religious structures symbolise far more than only the distinct identities of the caste.

Another observation was marriage practices, and how they entrenched divisions. In multi-caste-based villages, marriages predominantly occur within one’s caste, with cross-caste unions remaining rare. When suitable partners are not found within the village, families often seek matches from nearby villages of the same caste, reinforcing caste boundaries. This endogamous practice perpetuates the social stratification that defines village life, making it difficult for individuals to forge connections across caste lines. Interestingly, villagers often express their distinctions through phrases that reflect their social coherence: “It is not the tradition of our village,” “We belong to different surnames/castes, but we are brothers,” and “The honour of the village is the honour of all of us.” Such sentiments illustrate how, over centuries, communities have evolved to function like an extended family, even as sub-cultural practices rooted in specific caste identities persist. However, these bonds can fray when individuals from neighbouring villages settle in, bringing their own perspectives and potentially disrupting traditional practices.

In situations where one caste predominates, it often assumes leadership roles. Consequently, this situation leads to feelings of insecurity among minority castes. This dynamic becomes particularly evident during national elections. Candidates from dominant castes may receive preferential support, while minority castes may rally behind opponents as a strategy to secure representation and address grievances. This electoral behaviour reflects deeper anxieties about power dynamics within the village and the perceived need to protect their interests.

Let me end this write-up with an outcome of a brainstorming session held in a village in Khairpur Mirs, where participants discussed ways to mitigate caste differences in multi-caste-based-village. The consensus emphasised that education can dismantle caste barriers by fostering opportunities for upward mobility and a meritocratic society. Another noted point was that economic opportunities and job essential for loosening caste identities. Furthermore, the need for legal frameworks promoting equality and prohibiting discrimination was underscored, as these measures can provide a formal basis for challenging caste-based injustices.

The group recognised that political parties and rights-based organisations play a crucial role in addressing caste disparities and advocating for representation in governance. They also emphasised the importance of grassroots initiatives led by social activists to champion the rights of peasants, women, and minorities. A significant recommendation was to promote inter-caste marriages, as these unions often challenge traditional norms and facilitate greater acceptance of diverse identities within families and communities. By encouraging such marriages, villagers can actively work to dismantle the rigid boundaries that have historically divided them.

Over the past two decades, I have observed considerable changes in these multi-caste-based villages, largely driven by the catalysts of digital media and communication technologies. Social media campaigns as powerful tools have helped combat inequality and encouraged individuals to question traditional norms. Furthermore, increased exposure to global cultures through the internet has provided villagers with diverse perspectives, prompting them to reconsider caste-based prejudices and embrace a more inclusive worldview. This shift is particularly evident among younger generations, who are increasingly challenging the status quo and advocating for a more equitable society.

Apparently, Sindh’s multi-caste-based villages exhibit a harmonious surface, but they are underpinned by complex social dynamics shaped by caste. The interplay of unity and division reveals the intricate ways in which social identities are constructed and negotiated. Understanding these complexities is essential for fostering genuine social cohesion and promoting a more equitable society in the face of evolving challenges. As these villages continue to navigate the tensions between tradition and change, the potential for a more inclusive future rests on the collective efforts of their inhabitants to bridge the divides that have long shaped their lives.