A brief review of major pandemics worldwide reveals that the first significant cholera outbreak in British India began in 1817, with initial cases reported in Bengal. This outbreak persisted until 1824. Subsequently, a second wave emerged in 1826, continuing until 1837 and affecting various countries. Following this, the third pandemic, lasting from 1846 to 1860, was reported in Makkah and eventually spread to other regions. Meanwhile, the fourth wave occurred from 1863 to 1875, resulting in high mortality rates, particularly in Bengal, the Ganges delta, and beyond. In the years that followed, the fifth cholera wave lasted from 1881 to 1896, impacting Europe, the Far East, the Middle East and the Americas. Finally, the sixth cholera epidemic spanned from 1899 to 1923, but had a diminished impact on European cities.

Notably, the sixth wave (1899–1923) saw considerably less human losses compared to previous pandemics, such as cholera and plague. Most physicians and healthcare providers agree that this reduction was due to significant advancements in health, hygiene, municipal services, and medical training. Another common observation reveals that people initially denied the existence of the pandemics, followed by self-blame, and finally attributing the crises to divine anger or unseen forces.

Some, however, took the situation seriously: employing scientific methods and skills to combat and contain the diseases. This was a remarkable example of human resilience and trust in their abilities and knowledge.

Selected readings from Sindhi literature of that era confirm that such a dedicated and rational group also existed in Hyderabad, Sindh. Although small in number, but they were fully aware about the unfolded challenges posed by pandemics: the spread of disease, shortages of medicines, a lack of trained volunteers, regular supplies of food, potential loss of healthcare providers, and the overwhelming fear and panic within the community. Nevertheless, these individuals coordinated their efforts, implemented sensible measures, placed their trust in medical solutions, and committed themselves to serve their communities.

This brief article is but a humble tribute to their services. These noble people were: Dr Holmsted, Sadhu Hiranand, Dayram Gidumal, Bhai Kalachand Sahib, Bhai Molchand Menghraj and Rai Bahadur Seth Vishandas.

Dr Holmsted

Dr Holmsted served the citizens of Hyderabad from 1868 to 1884, playing an active role during two periods of cholera epidemics. He reports that the first case of the second cholera epidemic occurred in Hyderabad on 14 August 1869. We find out form him that the outbreak intensified at the beginning of September 1869 and began to decline by the end of October 1869. In total, 592 cases were reported, resulting in 364 deaths and 228 recoveries. He attributes the spread and severity of the epidemic to heavy rainfall, which contaminated drinking water tanks with harmful substances. He specifically mentions Tank Number 3 as a significant source of contamination. He adds that two other cases were reported in the jail during this period.

Except some of reports and a few letters to his friends, very little information is available about him. However, after leaving India/ Sindh he moved to England, where he married and settled in Exeter. He named his residence “Hope House, Heavitree,” located in a historic village that once existed outside the walls of Exeter in Devon, England. While the exact date of his retirement, the details of his marriage, and the year he moved to England require confirmation, it is certain that he was practicing medicine over there in 1884. In one of his letters addressed to Sadhu Hiranand, Dr Holmsted praises the warm and dry weather of India, contrasting it with England’s frequent rain. He reflects on the belief that love has the power to resolve all conflicts, acknowledging that while conflicts can cause distress, they also require resources to manage it effectively. Additionally, he asks Sadhu to convey his warm regards to his friends and family members in Hyderabad.

In recognition of his dedicated service, the people of Hyderabad constructed a hall in his memory, known as Holmsted Hall (now, Hasrat Mohani District Central Library, which exists near Mukhi house, Hyderabad). This venue has hosted numerous political gatherings and events, particularly in the colonial era.

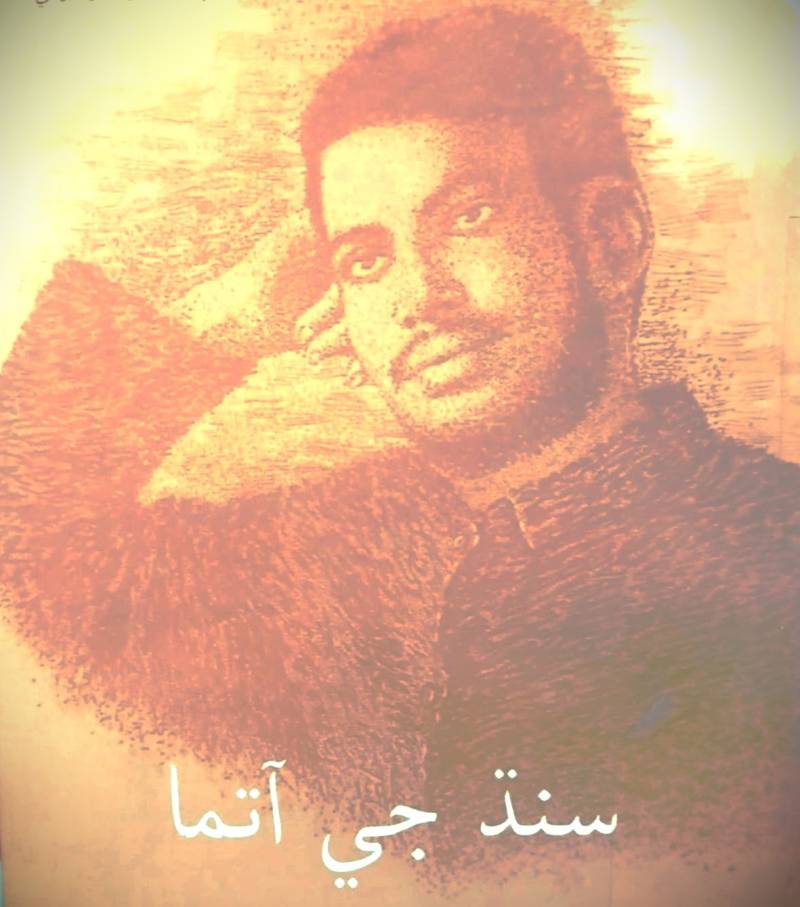

Sadhu Hiranand

Sadhu Hiranand was born on 23 March 1863, in Hyderabad. He emerged as one of the pioneering journalists for Sindhi and English newspapers, making significant contributions to the media landscape of his time. Beyond journalism, Hiranand was a prolific writer, social reformer, and educationist, deeply committed to advancing women's education. Along with Diwan Navalrai, he founded the Brahmo Samaj Movement in Sindh, which aimed to promote progressive ideas, particularly in the areas of girls’ education and women’s health services. He believed that the best profession for serving humanity is the practice of medicine. Therefore, he trained himself in midwifery, even though he was already a renowned editor of English and Sindhi newspapers. He did not hesitate to work as a compounder alongside Dr Jafar Kuli F. Mirza.

Throughout this time, Hiranand continued his self-study, ordering books through the post from Calcutta (now Kolkata) and asking his younger brother Motiram to find used or discounted books, particularly on women’s health. By this time, he had gained admission to Hyderabad’s Medical School and was preparing to sit for examinations scheduled for September 1886. In 1887, Hiranand expressed a strong desire to join Bombay Medical College, but his family did not approved his plan. Ultimately, after thoughtful analysis of the pros and cons, he chose to remain in Sindh.

In Hyderabad, Hiranand assisted Dr Charlotte Ellaby, a European lady physician. He helped with translations and organized classes for dais (traditional birth attendants). In August 1892, when cholera broke out in Hyderabad, it was the perfect opportunity for Hiranand to demonstrate his organizational skills, medical expertise, and unwavering dedication. He assembled a team of devoted workers, teaching them the importance of fresh air, light, warmth, cleanliness, and proper diet for the recovery of cholera patients. He immediately contacted medical suppliers in Kolkata to procure essential supplies and established an administrative office for coordination.

The citizens of Hyderabad in 1892 were fortunate to have a divine and God-gifted person who worked tirelessly during those fearful days, often until the early hours of the morning. Hiranand cared for even the most critical patients, many of whom were neglected by their relatives and friends. He truly embodied the spirit of an emergency responder. At the 4th Hiranand Memorial Meeting in Hyderabad, Hiranand Khemsing recounted a poignant experience: “In 1892, when cholera was at its peak, Sadhu Hiranand returned home one night at 2:00 am after tending to patients. Just as he was about to have his meal, someone called him to attend to a new patient. Without taking a morsel of bread or a drop of water, he left his seat to see the patient. His elder brother, Diwan Navalrai, urged him to eat something first, warning that attending to a cholera patient on an empty stomach would be a grave risk. But he replied, ‘None knows how a few minutes’ delay may render a case hopeless.’”

In fact, this paragraph was also a lesson in a Sindhi textbook, and it was there until the 1970s, but aftwerds due to unknown reasons it was removed from the textbook. He died on 14 July 1893 at Patna, India, at the age of merely 30 years. Dayaram Gidumal has called him a soul of Sindh, and eulogized him, saying that “he was a modest way-side flower, whose fragrance was for several years wasted on the desert air of Sindh.”

Dayaram Gidumal Shahani

Dayaram Gidumal Shahani was born on 30 June 1857, and was a multi-talented individual whose contributions to society were immeasurable. He played a crucial role in advocating for the legal marriage age for girls, promoting women's education, alleviating the suffering of widows, and advancing modern education. A visionary and a man of action, he was instrumental in initiating new thinking in Sindh. As an author, administrator, lawyer, judge, and staunch supporter of women's empowerment, he earned the title of the Rajrishi (King-sage) of Sindhi society.

Sadhu Hiranand trained himself in midwifery, even though he was already a renowned editor of English and Sindhi newspapers

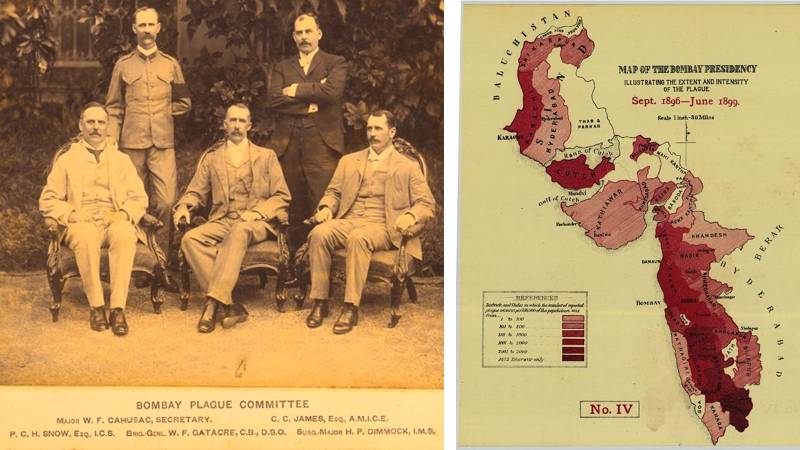

In 1896, plague cases were reported in the Bombay Presidency. By the first week of January 1897, several cases wre reported in Hyderabad, Sindh. The significant surge occurred from 8 January to 19 February, resulting in 33 reported cases and 28 fatalities. The government’s response included quarantine and evacuation of the affectees. On the other hand, the rising death toll instilled fear among residents. Many chose to migrate, while others erected temporary thatched houses along the banks of the Phuleli Canal. To prevent the disease’s spread, officials stationed volunteers at railway stations, and students from the Hyderabad Medical School were deployed at roads and crossings to control movement.

During this critical time, Dayaram Gidumal took a leave from his service and returned to Hyderabad to support his fellow citizens. Upon his arrival, he opened a private hospital at the Qeematrai Vernicular School (later at that site Kundanmal Girls School was constrcuted, now it is known as Jamia Arabia Girls High School). He was joined by notable figures, including Dr Piggt, Reverend Quancy, Dr Handersan, Bhai Molchand Aaj Waro (of the ivory trade), Bhai Kalachand (also called, Sawami Kalacahnd Sahib) and Bhai Kanwal Singh.

The hospital provided essential services, including food and the respectful cremation or burial of unclaimed bodies according to religious rituals. Dayaram managed the hospital with great diligence, arriving at 9:00 am to administer medicine and ensure that all patients received meals. He remained until 1:00 pm, after that he would disinfect his clothes and meet with his family. He returned at 4:00 pm to converse with the patients’ relatives. He also introdcued a ticket system that allowed only one visitor per ticket for brief meetings. In addition to his administrative duties, Dayaram reviewed the day’s expenditures and took long walks through the city with Bhai Kalachand and Molchand around 6:00 pm. His generosity extended to providing salaries for four doctors and 14 to 15 nurses. This hospital was run by volunteers and local funds, proved to be a successful model. By 15 June 1897, around 100 patients had been admitted, with 42 lives saved. The authorities of Hyderabad admired this model and opened their own hospital for plague patients, although both were closed on the same date – due to gross reducation in number of plague cases.

Dayaram Gidumal passed away on 7 December 1927, leaving behind a legacy of compassion and service that continues to inspire future generations.

Bhai Kalachand Sahib (also known as, Sawami Kalachand)

Bhai Kalachand Sahib was born on 6 April 1868, in his parents’ home in Gidwani Ghitee, Hyderabad. His father was Diwan Ramchand Gidwani. Bhai Kalachand was a devoted follower of the Sufi Panth, he dedicated himself to various practices of tapasya and vairag until 1890. During this time, he embraced silence. Eventually, he opened the doors of his Kutia—a small room filled with a few essential items—for darshan, allowing others to seek his presence or meet him. One of the regular activities at the Kutia at the night time was Katha, a form of religious storytelling that fostered community and spiritual connection.

Bhai Kalachand also took a stand against the tradition of Deti-Leti, which involved the bridegroom demanding exorbitant sums from the bride’s family. This practice left many marriageable young girls without prospects due to their families’ inability to meet these financial demands. In the 1800s, this tradition was particularly common among the Amils of Hyderabad. Bhai Kalachand organized the community to oppose this tradition and began delivering sermons against it. To further his cause, he authored a booklet titled Barahn Sawan Wari Bandi (A Booklet of Twelve Hundred Rupees), which gained popularity and became known as Kalachand Sahib Wari Bandi.

In the plague outbreak of 1897, Bhai Kalachand started to deliver sermons to inculcate resilience and patience to nerved citizens. Interestingly, impact of his lectures was profound. Alongside his companions, he bravely walked in the streets, offering assistance to victims of the plague and sang Bhajjans for their spiritual relief and joy. He worked closely with Diwan Dayaram Gidumal in caring for patients, visiting the hospital regularly to sing holy verses and narrate scared stories to the patients. His compassionate presence helped patients to alleviate their fears and frustrations in the face of death.

Bhai Kalachand Sahib passed away on 11 May 1919. His death anniversary is commemorated annually, celebrated over three days at Kalyann Mandir, a temple named after his takhallus, (pen name), Kalyann. He is fondly remembered for his dedicated service during the plague, embodying the spirit of altruism and selflessness in times of great need.

Bhai Molchand Menghraj

Bhai Molchand Menghraj belonged to the eminent Kirplani family of Khudabadi Bhaibands. He was spiritually connected to Bhai Khemchand Kirplani, and after Khemchand’s death, he became the companion of Bhai Keshuram. Following the death of his father, Molchand entered into the ivory trade. Soon, he successfully established himself and earned the nickname Bhai Molachand ‘Aaj Waro’ (of the ivory trade).

At the time of the plague outbreak of 1897, he joined forces with Dayaram Gidumal, personally dedicated himself to the care of patients. He used to set up cots for the sick and got permission from the in-charge doctor to use one of the hospital rooms. Once permission was granted, he assigned that room to his servants to stay in the room and prepare food. The servants were instructed to rise before dawn to cook a cauldron of rice and warm up half a maund of milk. The servant were instrcuted that everything must be ready before sunrise.

Every morning, Bhai Molchand would arrive to serve each patient a glass of milk and a plate of cooked rice. He also provided fresh vegetables, flour and other essential food items to the patients and their families. Eventually, he established a store within the hospital premises to supply patients and their attendants with necessary provisions. He spent Rs 75,000 from his own pocket to support the hospital.

One day, a patient passed away, and as the body began to swell, no one was willing to wash it. When Bhai Molchand discovered that unclaimed body, he took it upon himself to perform the necessary rituals before cremation. He washed the body, despite its condition, showing immense compassion and respect. After a few days, he noticed that his hands had become infected. Upon consulting a doctor, he learned that the infection was caused by the swollen body he had washed. Nevertheless, Bhai Molchand continued his selfless service at the hospital until its closure in June 1897. His dedication in those challenging times is a vivid testament to his belief in the general good.

Rai Bahadur Seth Vishandas

Rai Bahadur Seth Vishandas was a prominent member business family hailed from the Manjho area. The family was already famous for their public service. Over time, Rai Bahadur Seth Vishandas established a network of businesses in Karachi, Hyderabad, and other towns. However, he maintained homes in both cities ie Hyderabad and Karachi. He had already earned a good name in opening a plague hospital in Karachi. Later in 1889, he also opened the plague hospital in Kotri. In addition to his healthcare efforts, Rai Bahadur provided essential food items to families in need.

In 1914, some cases of plague were reported in Hyderabad. Instantly a panic ensued. Those who could afford to migrate fled to safer towns, while many others, lacking family connections or financial means, were left stranded. At that time, Rai Bahadur’s Vishan Nagar was well-established, featuring gardens and numerous residential structures. He graciously opened these residences to the displaced families. As the number of migrants grew, he constructed thatched shelters to provide them with a safe haven. He also established a low-priced grain shop, allowing residents to purchase food at reasonable prices, and opened a travelers’ lodge for those passing through. Recognizing the children’s educational and health needs of the community, he founded a school and hospital in Vishan Nagar. The inauguration of these institutions took place on 10 April 1916, presided over by the then Commissioner of Sindh William Henry Lucas. The event was attended by notable figures and officials from across Sindh, celebrating Rai Bahadur's commitment to uplifting the lives of those around him through compassion and service.

I believe this write-up about the acts of noble souls of Hyderabad in times of cholera and plague may illuminate new paths for young men and women, encouraging them to set new standards of compassion and service. Assuredly, their legacy prompts us to reflect: can we not also embrace this path of altruism and rationality?

Let me conclude this essay with heartfelt gratitude to the authors whose works I have consulted and referenced. Their names are: Tahalram Asudumal, Dayaram Gidumal, Molchand Meghomal, Mirza Qaleech Baig, Motiram Satramdas Ramwani, and the cholera and plague reports of the Bombay Presidency. I must acknowledge their invaluable contributions to this important narrative.